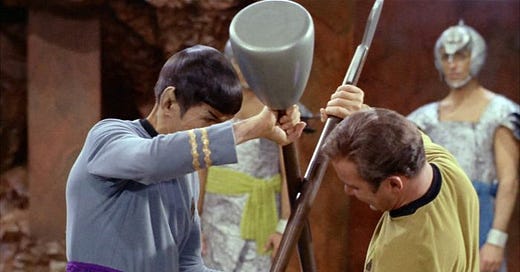

Because I’m a college professor, and because my kid’s in high school, my life continues to follow the logic of academic time: the new year begins not on January 1st but in the fall. That feeling is amplified by the Jewish High Holidays, which came a little late this year: the new year of of 5785 arrived nearly simultaneously with my birthday, another marker of something ended and something new beginning. I’m 54, though I feel much younger. And I’m writing this (in a notebook) on Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar, and typing it on the secular morning after, and thinking about all the different kinds of time that shape our lives: cyclical time, historical time, subjective time (Bergson’s durée), sacred time, and even the amok time of poor old Mr. Spock, a very logical fellow in the grip of madness that is the Vulcan mating season, depicted in mortal struggle with the guy who usually gets all the girls, Captain Kirk, above.

We feel, don’t we, that we are living in apocalyptic times—it’s always the apocalypse for someone, somewhere, but the Internet means we are conscripted as witnesses in ways we weren’t to the Rwandan genocide or the wars in the former Yugoslavia. I suppose 9/11 inaugurated the new era of hyper-visible apocalypse, now. It’s apocalyptic in Israel and Gaza and Lebanon; it’s apocalyptic in Ukraine; it’s apocalyptic in Florida and western North Carolina; it’s apocalyptic every time Donald Trump opens his miserable mouth. If he becomes president again, it will be because he’s frightened enough Americans into believing that these are apocalyptic times and he’s the outer-borough messiah who will magically wind back the clock to when America was great—some whitebread fever dream of the 1950s, when immigrants and people of color knew their place. Kamala Harris has the harder task of persuading voters that the apocalypse is not yet; that we still live in time, not eternity, and are still capable of meaningful action. She is almost literally the candidate of the future, which was once a winning proposition, a la JFK’s New Frontier. But faith in the future is in short supply nowadays.

The night before Yom Kippur is Kol Nidre, an Aramaic phrase which translates literally to “all vows.” Like the shema, it is not, strictly speaking, a prayer: we address it to ourselves. On Kol Nidre, Jews dissolve all contracts and atone for those we failed to fulfill in the past year, while acknowledging that whatever fine resolutions we develop for the coming year may also fall short. Yom Kippur itself is a kind of super-Shabbos—especially when it actually falls on Shabbos, as this one does. A time to step away from daily concerns and doomscrolling; a time to act as if the messiah had already come and tikkun olam, the repair of the world, were already accomplished. I’m not supposed to do any work today, or eat or drink, or have sex, or anoint my body, or wear leather. Writing in this notebook is, I think, okay. Because I’m thinking about time.

It’s one thing to escape the news cycle for twenty-five hours with the armamentarium of ritual; it’s quite another thing to effect a genuine escape from the apocalyptic time imposed on us by capitalism. I mean the logic of exchange that dissolves all values into money, and money into time. How to subtract extraction from the equation that dissolves so many of my hours into a morose and meaningless panic, hours that could have been devoted to contemplation or connection? Last night, when I got home from the Kol Nidre service at Mishkan, I deactivated my Twitter account. If I do nothing for thirty days, it will be permanently deleted. I hope I hold out. The app formerly known as Twitter was my last social media addiction, the last dopamine rush I couldn’t let go of. It hasn’t been fun for a long time; it’s a panic pusher, swamped by bots all chirruping the malevolence of a fascist billionaire with more power than any unelected individual should ever be allowed to have. Even the good guys on Twitter are no fun anymore; even the literary tweets, which used to connect me with genuinely thoughtful essays and conversations, have taken on a sheen of sameness, homogenized by “the discourse” that lets a thousand Sally Rooney reviews bloom and chokes out everything else. Everyone on that app is a slave of the hot take, addicted to an illusory Now, harried by the fear of being out of touch (bad) or seeming so (worse). Last night my rabbi pointed out that between stimulus and reaction it’s possible to breathe—to pause. Twitter, and the logic of the Internet as an instrument with the single purpose of extracting value from its users, destroys that pause.

At the college where I teach, and at universities all over the world, hands are wrung over the crises in higher education in general and in the humanities in particular. Professors and administrators alike scramble to prove the relevance of their disciplines, to turn, say, English, which I teach, into a hot take: majoring in English is good, actually. This is true, yet the rhetorical environment in which we make the argument is a toxic one, in thrall to the extractive logic of the times. College is more expensive than ever, and our state and federal governments have pushed the cost onto individual students, to ruinous effect, especially for first-generation students and students of color. Public re-investment in higher education would pay incomparable dividends to our society, but political stalemate means the best we seem able to do is for the president to cancel student loans and for the hyper-conservative Supreme Court to reinstate them again. Unless and until politicians can be persuaded that it’s of political benefit to them to fund the educational infrastructure of our society, many students and their families will understandably regard higher education with a jaundiced eye. Not because they’re worried about left-wing indoctrination (as if!) but because of the massive debt students are routinely expected to assume. No wonder they look at college as a transaction, and that in large ways and small my colleagues and I are encouraged to think of them as customers. No wonder that so many of the students I encounter who might have wanted to major in English, or philosophy, or history, major in business or neuroscience instead.

In my capacity as chair of the Lake Forest College English Department, I must bend to the logic of shilling for English as a place where students can build the skills employers want. But the Rarebit Fiend wants to argue against the grain of relevance or the monetary value of an English degree. College, whether it’s for two years or four years, ought to offer a kind of sabbatical time. Bring back the ivory tower! It’s true that no student of mine can afford in any sense to cut themselves off from the world like a medieval monk: they have families to support, political commitments, and those loans to think about. But after a dozen years of compulsory education, they deserve a pause; they are entitled to a few years to focus on developing their minds, to follow whim and curiosity, and to discover pleasures more rigorous and rewarding than the dopamine rush of the eyeball farm to which we’ve indentured ourselves.

I saw Megalopolis, and I had a hell of a good time, not in spite of but because of its cringey excesses. I loved the scene, now a meme, in which the Robert Moses/Howard Roark-like hero played by Adam Driver spits at Nathalie Emmanuel’s character, “You think that one year of medical school entitles you to plow through the riches of my Emersonian mind?” Laughable, right? Yet we are all of us entitled to plow the riches of Emersonian minds, not least our own, and college is precisely the place that ought to make such plowing accessible. Ralph Waldo Emerson offers as good a model as any for the kind of mind we so badly need today: questing yet ironic, idealistic yet dialectical. To read an Emerson essay is to experience a mind like your own, but heightened, for it is a mind that changes. Emerson never makes an assertion without a counter-assertion; he is never polemical without diverting some of that polemical energy against his own preceding arguments; his sentences, like his moods, do not believe in one another. He is not a party, but a man; not a consumer-producer of hot takes, but a thinking, mortal individual who lives in the stream of time without being knocked over by it.

My own college education was a privileged one—economically, yes, but also by dint of its having happened in the twentieth century. My own Emersonian mind was forged in that century: does that make me a relic? Well, relics can be valuable and the objects of heroic quests! I can’t bequeath such a mind to students born in this century, but I can try to model an approach to life and learning that is active rather than reactive. If you want to be the protagonist of your own life and not just a worker bee, or worse, a set of eyeballs for the tech companies to monetize, you have to pause. You have to develop habits of contemplation, of reading and writing at the slower pace required if you are ever to actually communicate with anyone, rather than push their buttons. You have to take the time to find out what it is you want, trying out approaches and disciplines and worldviews that your inevitably provincial upbringing never revealed. It will pay off in the end, and in the meantime, you’ll develop habits of intellectual freedom that will serve you, and your country, for a lifetime.

The time you save may be your own.

I so enjoyed this one— a perfect statement of what these holidays are intended for, or so I would like to think. So you don’t feel 54, we’ll I just started feeling my age so you have more than thirty years to catch up to yourself!

dang, this is pretty neat. i wish this guy was my dad.