This absurdly handsome fella is Benjamín Labatut, the enigmatic Chilean writer whose first book to be translated into English, When We Cease to Understand the World, I devoured in an astonished fever. It’s a speculative nonfiction novel about mad scientists, or more precisely, scientists driven mad by the tendency of science to lead them up to and then blow right past the boundaries of common sense. Frankenstein is the presiding spirit over this collection of stories charged with lyric dread about figures famous and obscure: the genius mathematicians Shinichi Mochizuki and Alexander Grothendieck; Fritz Haber, the German-Jewish chemist responsible for both the synthesis of nitrogen (a boon to agriculture that saved hundreds of millions of people from starvation) and for the chlorine gas that inaugurated the age of chemical warfare in World War I, most notoriously at the Second Battle of Ypres; Karl Schwarzschild, another German Jew, the theoretical physicist who solved Einstein’s equations for general relativity from the trenches of that same war and who gave us the concept of the singularity, aka black holes; and Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger, whose names have become bywords for the ontological uncertainty revealed by the operations of quantum physics—an uncertainty characterized by Einstein’s bitter denunciation, “God does not play dice with the universe.” To which Labatut has Niels Bohr retort, “It’s not our place to tell Him how to run the world.”

The undermining of our everyday reality conducted by these scientists moves in tandem with the undermining of social bonds and of morality over the course of the twentieth century. Perhaps the central quotation is this one, a vision of lucid darkness that Labatut bestows upon Schwarzschild as he lies dying from an autoimmune disease in 1915, the same year he solved Einstein’s field equations from the trenches of the Russian Front. For the dying Schwarzschild the singularity—the collapsed star from which nothing, not even light, can escape, but also a location from which, in theory, an observer could see the future—is a monster of a metaphor:

If matter were prone to birthing monsters of this kind, Schwarzschild asked with a trembling voice, were their correlations with the human psyche? Could a sufficient concentration of human will—millions of people exploited for a single end with their minds compressed into the same psychic space—unleash something comparable to the singularity? Schwarzschild was convinced that such a thing was not only possible, but was actually taking place in the Fatherland…. He babbled about a black sun dawning over the horizon, capable of engulfing the entire world, and he lamented that there was nothing we could do about it. Because the singularity sent forth no warnings. The point of no return—the limit past which one fell prey to its unforgiving pull—had no sign or demarcation. Whoever crossed it was beyond hope.

Labatut’s book locates the black sun of irrationality at the center of the Western civilization that did its level best to destroy itself, convulsively, in the period 1914-45. (“We have reached the highest point of civilization,” Schwarzschild writes in 1915. “All that is left for us is to decay and fall.”) But although his book depicts many black deeds—particularly in the first and least fictional chapter, “Prussian Blue,” which follows the ironic career of Fritz Haber, whose experiments with poison gas would lead eventually to the creation of Zyklon B—the most profound horrors are conveyed to the reader’s imagination indirectly rather than by direct depiction.

When We Cease to Understand the World, in its blend of fact and fiction and the dark lyricism of its prose, bears many similarities to the writings of Roberto Bolaño, W.G. Sebald, Olga Tokarczuk, Laszlo Krasznahorkai, and Daša Drndić, with a bleak strain of misanthropic humor that I associate as well with Thomas Bernhard. These authors work in a genre I have come to think of as Black Books: books stained by a moral and existential dread that sutures the ordinary workings of the human heart to the most appalling historical crimes. Most often, World War II is the source if not the subject of these books—the origin of the black light they refract but refuse to reveal in more conventional narrative forms. These are novels without heroes or redemptive arcs; they attempt to represent what cannot otherwise be represented; they operate by generating imaginative resistance in the reader, an awareness of the awfulness behind closed doors. I am reminded again of Frankenstein, and how Mary Shelley never reveals to us either the exact means that created the monster nor the details of his appearance; his horribleness must be inferred from the reactions others have to him. The Universal films, splendid as they are, sacrifice this quality of moral indirection for the more visceral impact of the icon. We stare in fascination at its ugliness, but do we see ourselves in its mirror?

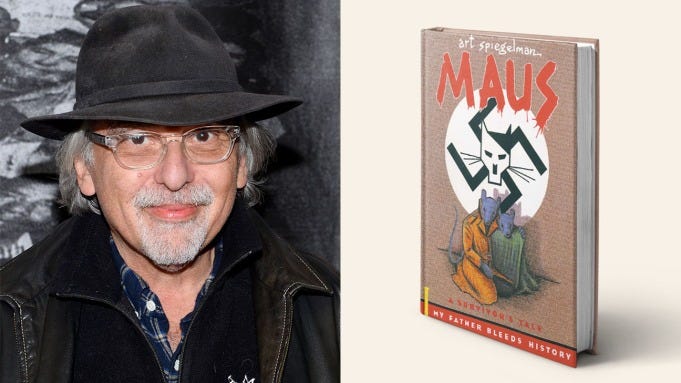

Maus is not, to my mind, a Black Book. It confronts the singularity of the Holocaust too directly for that. But the story of Maus as we are presently living it—Maus as political football, Maus as banned book—that gives me glimpses, negative images of horror, in the manner of Bolaño’s 2666 or of Sebald’s Austerlitz. If a stylized yet direct account of one survivor’s experience of the Holocaust is deemed unreadable, censored as collateral damage to the American right’s whitewashing of history, then perhaps it too enters the shadow realm of the Black Book, a book with implications so frightening that we can never confront its object. As in certain horror films, such books work by never fully revealing the crimes around which they are constructed, arousing a terror from which most media’s shock and awe ceaselessly distracts us.

Maus—which by pure coincidence I happen to be teaching this week in my American Graphic Novel course—reveals the human by concealing it, literally, behind paper masks—mice, cats, dogs, pigs, a frog or two, in one awkward instance a gypsy moth. Like James Whale’s Frankenstein, it seizes upon the power of the icon to further its allegory, to lucidly expose the madness of anti-Semitism and systematized mass murder. A Black Book, on the other hand, may flirt with allegory but must ultimately refuse it—there is no key to these mythologies.

Your bait of falsehood takes this carp of truth:

And thus do we of wisdom and of reach,

With windlasses and with assays of bias,

By indirections find directions out

So says Polonius, that spymaster of catastrophic ineptness, who gets too close to Hamlet’s mystery and dies never suspecting its real nature. In a Black Book, the bait of falsehood—the fictional—doesn’t pull a carp of truth out of the dark water, it pulls the reader into it. As in the theories of Heisenberg, there is no truth that we might scientifically “With windlasses and with assays of bias” discover that isn’t affected, changed, by our angle of observation. We must include ourselves in what we study, put ourselves at risk. Was Fritz Haber a bad guy or a good guy? It’s a Polonian question, and always already wrong.

The Polonian obtuseness of the Tennessee school board is equally sinister and inept. They have returned Maus to the top of the bestseller lists—fine! But will the attention paid to this particular whitewashing—done, as always, in the name of protecting the innocent—distract from the more comprehensive efforts to whitewash the criminal history more native to these shores? I speak of course of the effort to ban the chimerae of Critical Race Theory, of the 1619 Project, of legislative efforts to bar white people from having to feel uncomfortable, so that they need never ask Eliot’s question, “After such knowledge, what forgiveness?” If there are no Black Books in my special sense on the chopping block, that doesn’t mean that they don’t make the same uncomfortable demands upon their readers, calling upon us to refuse the peculiar, selfish, deadly innocence that is every (white) American’s birthright.

Hannah Nikole-Jones, the author of The 1619 Project, posted this tweet a few hours ago, with the indelible line: “Efforts to memory hope the truth about US are not new.” No doubt that’s a typo for “memory hole,” but it’s an alluring one. Memory hope is a good term for the impulse to deny history by insisting on a reversible teleology that doesn’t simply bend toward justice—as though justice were a law of the universe rather than the product of collective struggle—but that absolves us of any responsibility for the past. Memory hope conjures media phantoms like the Greatest Generation; memory hope assures us that, just because our ancestors didn’t happen to own slaves, the legacy of slavery can have no hold or meaning for us. We turn a blind eye to the immense wealth generated by slavery, the fabled streets of gold that my turn-of-the-century ancestors came to America to find.

Tony Allman- I understand all that, but being in the schools, educators and stuff we don’t need to enable or somewhat promote this stuff. It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy.

Memory hopers like Tony Allman—a member of the McMinn County school board, the full transcript of whose meeting banning Maus can be read here—believe there must be more appropriate and less discomforting means by which children can be instructed about the Holocaust. Perhaps they could screen Life Is Beautiful or Schindler’s List for their eighth graders—films that are the very opposite of Black Books in their adherence to narrative tropes like the hero’s journey, reducing the horror they supposedly depict to inspiring stories of individual sacrifice and heroism (preferably by non-Jewish characters).

Tony Allman and his fellow memory hopers have inadvertently taught us a lesson; they have elevated Art Spiegelman’s Maus, in my eyes, to the status of a Black Book. The wounded, mordant allegorical action of a Black Book is not to be found in its pages, but in its consecration as something forbidden and thus bearing the marks of a complex truth. It is not the nudity or curse words or atrocities depicted by Maus that have given it another shot at shaking the complacency of an educational-industrial complex designed to reproduce apolitical docility. It is that complex’s refusal to let us see it.

I prize the genre of the Black Book, ethically and aesthetically. I believe that what we most need or desire to see can never be depicted without falsification, and that’s why so much of my own fiction centers on dramatizing the desire to know what can’t be known. Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy refracts the black sun of the Holocaust through the unknowable soul of a figure rather like my mother, the daughter of Auschwitz survivors. My new novel, How Long Is Now, sends its writer-protagonist on a tragicomic quest for a usable father, now that his actual one has been broken. Narration that runs up to the cliff of the unnarratable and runs right over it, like Wile E. Coyote—that’s what a Black Book, with its unstable mixture of fictional and nonfictional perspectives, shifting constantly between wave and particle, can do.