Concord, Chapter 8

The North Star

On his way out he glanced into the Archivist’s office. Lionel sat as if dreaming before an array of screens, each depicting its sliver of lost time: flood reports, crop failures, food riots, troop movements. The vague, ineffectual faces of justly forgotten officials flickered past. He inclined his head imperceptibly in acknowledgment of Saul’s passing, and Saul gave him a little wave. Lionel didn’t wave back.

He had just climbed the steps into the library lobby when an electronic tone, high and fretful, rang out of the speaker over the door, echoed by identical tones at different distances, all throughout the town. A familiar voice made him flinch—he wished to God he hadn’t had the idea of giving the Concord alert system Suzanne’s voice. Marco had never said a word to him about it, for or against, though it would have been simple enough to change. It was the voice of authority, measured yet concerned, echoing throughout the village: Code Green. Code Green. This is a special weather event. Residents are advised to return to their homes or their designated action area within—a brief mechanical pause—twenty minutes. This is a valid Code Green.

“Oh dear,” said Mrs. Riordan, rising from her station behind the circulation desk. “I can’t say I’m surprised, the floor’s had a funny little skip to it all day. Mr. Klein, would you mind helping me for a moment? I need to see who might still be in the reading room and make sure they have time to get to their action area. Will you check for me?”

“Of course.”

The reading room at first appeared to be unoccupied—then Saul saw Dr. Moody snoring in a plush chair by the projected fireplace. He stood over her, considering for a moment—the gray tangle of hair, the ragged raincoat, the blotchy skin. She smelled like smoke and rain. He put a hand on her shoulder and shook her, gently at first.

The glazed eyes opened slowly and she reached up to grasp him with her fever-hot hand. “Charles? Is that you?”

“I’m afraid not, Dr. Moody.” He tried to smile.

Her eyes focused. She gripped his hand more tightly. “Saul Klein! What is it? Do you have news for me?”

Saul looked around in despair for Mrs. Riordan, but she was nowhere to be seen. “Not the kind of news you’re hoping for,” he said. “It’s a Code Green. We’ve got to get you home.”

“I am home,” she said, gripping his hand. “Anywhere I am is home, if you’re there too.”

He tried, gently at first and then forcefully, to pull his hand away. Her face twisted open, eyes gone wide in horror. “Dawn!” she shrieked. “Dawn!”

Through the high windows he saw the eerie pale green light that gave the alert its name. There was nothing for it. He gripped Dr. Moody under the arms and dragged her kicking and screaming to the library’s action area—which was of course under the surface, back in the Archive. At the top of the steps he gripped her firmly from behind. “Listen,” he said. “Elizabeth, listen. Don’t fight me. We have to go downstairs.”

She sobbed like a child, but no longer resisted him. He carried her awkwardly and was met on the landing by the anxious face of the librarian.

“Oh, the poor thing,” she said. “Lizzie, do you remember me? It’s Charlotte. Lizzie, come downstairs with me and we’ll have a cup of tea.”

She held out her hand and Dr. Moody took it, simpering like a little girl. The librarian looked up at Saul.

“We’ll take it from here, Saul. Thank you.”

He was oddly reluctant to let her go, but he did. The two women went down the stairs slowly, clutching the banister, Mrs. Riordan murmuring soothing nothings in Dr. Moody’s ear.

He walked home. The streets were silent and empty—a Code Green, though no disaster, was no joke. The projectors had been switched off as a precaution, and the blank facades of the buildings jutted like a jaw full of broken teeth. Steel shutters covered the windows. From the bottom of the bowl of the town he saw the sky carrying on its surreal revolutions, masses of black clouds clustering lower and lower until they seemed to be interpenetrated by the tips of the pine tops. He broke into a lurching run, feeling his sea legs—his village legs?—desert him as the pitch grew more extreme. The navigators did their best to evade the storms and waterspouts erupting at unpredictable intervals out of the overheated ocean, but sometimes they blew up too quickly. There was nothing to do in such cases but to power through, trusting in the Founders’ wisdom.

By the time he made it home the rain fell in thick, honey-heavy drops. Saul peeled off his wet clothes and sat on the edge of the bed listening to the water hammering on the roof, while the window became a gray glassy blur as one sheer curtain of rain after another came slamming against the sides of the house. The room itself was in motion, and it was no longer possible to pretend that he didn’t feel nauseated. He lay spread-eagled on the bed, clutching the posts, feeling the sickening lurch of Concord as it followed the invisible slope of the seas. Our little world, he thought, a plank in reason, sufficient unto itself until the void it floated in asserted itself as mass and liquid, the birthplace of titanic forces, alive with the doom that could send them to the bottom of the sea any time it chose. He knew the dangers well and was helpless to prevent them. Grief stuck in his throat. How he wished, as in the Archive, he could pull the plug and go back to the moment of his choosing. But what would he find there? What kind of world? The seeds had been planted long before Lila’s birth, before his own birth. Every living thing has its origin, and from that origin it begins to die.

The darkness outside was total. The room canted as though it were being carried on horseback and he heard the tinkle of glass. Fuck. He turned himself laboriously over and groped for the fallen photograph of Suzanne sliding on the floor, bits of glass glittering. Books thudded to the floor; the door rattled in its hinges. The room stood revealed for what it was: a second-class cabin on a cruise to nowhere. Saul shut his eyes, then opened them. It had been many years since he’d been seasick, but there was no evading the sensation: a kind of helpless pitching into the depths of one’s own flesh, making the sufferer wish acutely to die. The feeling was concentrated between his clamped lips, in the sweat streaming from his armpits, in his throat. For a nauseous half hour he wasn’t thinking about Suzanne, or Lila, or Dr. Moody, or anyone at all. He groped his way to the bathroom sink and retched. He was entirely body, no thought at all. In such misery is a kind of bliss.

By midnight the Code Green was over. The revolutions of the floor diminished and his nausea departed. Concord, when all was said and done, was only a vessel on the sea, albeit on a vast scale; though it was possible to forget that fact for weeks and months at a time, a Code Green was a forceful reminder. But the storm had passed and the rain had thinned into a light, comfortingly intelligible series of streaks against the window. The semblance of peace had returned.

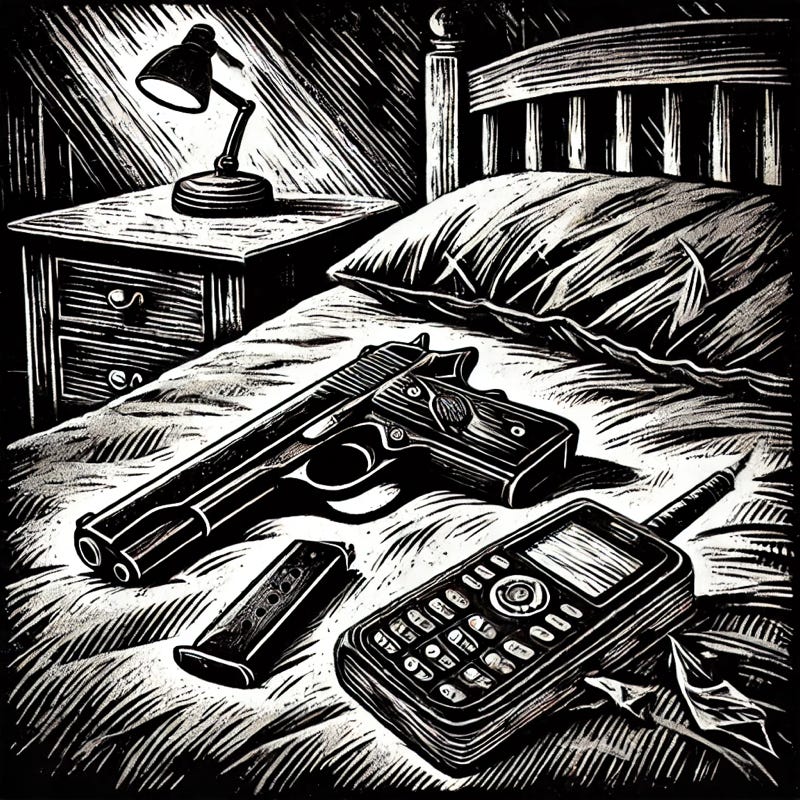

He got a broom and swept up the bits of glass, careful not to step in them. He pushed the bed and dresser back into their places. When he did so, he saw that the hidden board had popped out like a tooth from a boxer’s jaw. He bent down to push it back into place and paused. His door, of course, didn’t lock. He braced the doorknob with his chair before kneeling down to haul Ali’s out of its hiding place.

He half expected to find a message from the Painter inside, or that Ray had replaced the bag’s contents with bricks, or old books, or nothing at all. But everything that was supposed to be inside was inside. He took out the gun and checked the load. Had he known it was there when the Constable and his goons came that morning, would he have acted differently? Was his life so dear to him that he should not have taken a stand in defense of the strangers? For ye were strangers yourselves in Egypt. A bitter taste traveled up from the back of his throat, remembering childhood seders in Albany Park, his father looking down the groaning table lined with cousins and aunts, deciding who would be the wise child, the wicked child, the simple child, the child who does not know how to ask. His father, Isaac Klein, with his scruff of beard and high forehead and glinting glasses, a face young Saul had taken to be identical with that of God. He had not thought of him for many years; the elder Klein had died of an aneurysm at forty in a world shining with precarity, yet intact. Saul had not really expected to outlive him. Why did the old man seem to hover before him now, in this place, on the godforsaken ocean, crouched like a thief before a heap of ill-gotten goods? He tried to shake off the image of his father lifting his glass in the dark apartment, calling: Next year in Jerusalem!

The gun. The phone. The bag of money. The notebook, still damp to the touch. He opened it and a few photos spilled out. There was Ali, about thirty years old, head shaved, his expression serious, cheek by jowl with a girl of twelve or thirteen, with his identical eyes. Ali unsmiling in a candid shot taken in a tent-strewn marketplace, one hand raised in salutation or warning. Was he addressing some sort of crowd? Another photo of a woman with a round face and a green scarf covering her hair. The same woman, noticeably thinner, now with cropped gray hair uncovered, her tense, anxious eyes floating over a thin smile. And finally, a photo of Ali and a healthy-looking Jean-Baptiste on a dock, grinning, their arms thrown over one another’s shoulders. He thought he recognized the sailboat behind them, held the photo up to the light to make out the name and registry. No good. He found a magnifying glass in his desk and brought it back to scan the words: L’Étoile Nord, Dakar.

The North Star.

If not for the photos he could almost have persuaded himself that Ali and his companions had never existed, that he’d never seen their boat, battered and ill-equipped, yet seaworthy. He could have put aside the Painter’s insane hope.

He had Ali’s things. The phone. The notebook. The money. The passport. The photos. And the Glock, the most ambiguous gift of all.

Saul remembered that a gun is always heavier than you expect. He hefted it, smelling its oil, testing the weight, grateful in a way. There was no one he could imagine pointing it at but himself. Since he’d acquired the gun, that possibility was never remote from his mind.

He paged through the notebook, using tweezers to try and separate the wet pages. It had the look of a kind of journal or ship’s log, and he wondered the handwriting—all in French—were Ali’s. The script was tiny, the words abbreviated and gnomic. He flipped automatically to the last pages, translating haltingly to himself:

Jan. 1. New Year’s Day. Rationing. J-B slightly better. Y in contact with Mamère.

Who, or what, was Mamère?

Jan. 4. Mamère unresponsive. J-B can hold down only a little water. Y up 47K.

Forty-seven thousand what? Cryptodollars? Or was cash somehow still king? He looked at the stacked bills with a new respect; they might be worth holding onto after all. Or were they merely counters, for a card game maybe, to while away the hours while they waited to come across something of real value. He had no doubt in his mind that Ali and his companions had been, at best, scavengers, combing over the remains of whatever scraps they could find in an effort to survive, to propitiate “Mamère.” The money was only a game. He picked up the satellite phone again, wondering if they had reported their find, surely their most astonishing, before trying to come aboard. Did Mamère, whoever or whatever she was, know about Concord? “Mamère unresponsive.” That did not mean that no one had heard.

Jan. 5. Still not able to raise Mamère. Are we alone? J-B takes broth. Y insists our target on.

Jan. 9. Four days Sargasso.

The Sargasso Sea was a mass of water in the North Atlantic, the only named sea with no coastline, only more water to surround it. It was a mythic locale in which mariners were apt to find themselves lost and adrift, their sails abandoned by the wind. It meant, in a word, breathlessness. Though they had found Concord skating somewhere in the vast dish of the Pacific, Ali and his tiny crew might have endured the deadness, the depleted oxygen of one of the dead zones that proliferated the world’s oceans thanks to a paucity of phytoplankton. The dead sea absorbed oxygen from the atmosphere at a prodigious rate, turning Texas-sized patches of air at times into something barely breathable. Perhaps they had oxygen tanks on board, or maybe it was the poor air quality that had made Ali’s brother so sick.

Y insists our target on. What did this mean? He did not trust his meager understanding of French syntax, and wished again that his mesh might be reactivated, if only for a moment. There had been no foreign languages in the Paraverse; everyone understood everything, instantly. Still, la cible ought to have been clear enough: target, mark, quarry. Concord?

The last entry was undated:

Sighting. Y says avoid, monitor, find Mamère. I say J-B needs help now. Supplies v. limited. Y reluctant. J-B can’t vote. Risk it.

They had wallowed in their windless boat, set adrift from Mamère, her lost child, lost limb. Jean-Baptiste was dying; Yann defiant but too young not to trust in the judgment of his uncle, who would steer them right and true. Ali, with reasons for living that he had surrendered at last. On open water, with no hope for replenishing their limited supplies unless they could make their way back to Mamère or find succor with Concord—with Saul. Grimacing, he flipped the pages back; but in previous months Ali had been, if anything, more laconic:

Oct. 2. MV Laramie, Guinea f. 3 units. No resistance. Units of what?

Oct. 9. Containers. 0 units. No help. Sunk as hazard.

Sunk because it was a hazard, or sunk to create a hazard? Aucune aide—did that mean no help had been requested, received, or offered?

Oct. 16. With Mamère. Repairs.

Oct. 17. Repairs.

Oct. 19. Repairs complete.

What had happened on the 18th? A gap followed this grouping.

Nov. 5. M to be safe? My trust in God. 4 units from ferry. All sank.

Who or what was M? The daughter from the photos? The woman? M sera-t-il en sécurité? Safe from what?

“Ma confiance en Dieu,” he murmured.

Were the Constable to recover this journal, Saul thought, he would have felt more fully justified in the hygiene measures he had taken. Were he capable of feeling guilt, this evidence would surely have assuaged it. Ali and his crew had almost certainly been pirates of a kind. Had they remained alive they might well have found a means of contacting this Mamère—Saul was convinced it was some sort of vessel. The results might have been catastrophic.

Duty and self-interest alike demanded that he turn the evidence over to the Constable—or perhaps to the Commodore, to keep him on side. The Constable had the armed force, but the Commodore was the center of moral authority, the figurehead appointed by the Founders to safeguard the floating community’s sovereignty. Saul told himself that there was no meaningful punishment that either could inflict. Punishment might even bring a bit of light to his existence, as proof of some kind of purpose, a further role to play. What we miss in Concord, he thought, is meaning. He searched for it inside Ali’s black bag but found again only the fragmented photos. What had the Painter made of it all? Saul thought he had given Ray his answer, but now he wasn’t so sure.

Carefully, almost tenderly, he packed up the pirates’ leavings, the human things. He turned the phone on, briefly, and this time thumbed through the call record to see if it had been used before. The call log was empty. He wrapped the gun in an old T-shirt and tucked it in on top. Zippered the bag, he pressed the air out of it so as to roll it into a tighter bundle, and returned everything to its hiding place.

The nightmare glare reflecting from his window had given way to ordinary night. In the clinging water droplets he could make out a few reflections from the re-illuminated streetlamps. The moon cast a wavering pale light onto the counterpane. He listened. Wind soughed in the pine branches, roof beams creaked. From below and all around the brilliant hush that the villagers had trained themselves not to hear, the deep whispering engine of the world as it was, their eternal present tense, invisibly surrounded by the sea.