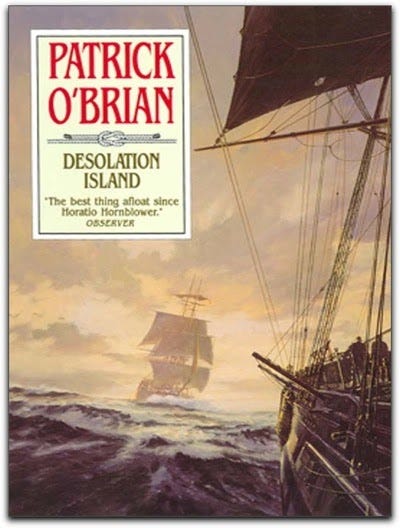

[Having recently reread (or re-re-reread) Desolation Island, it’s a pleasure to return to my original thoughts on the novel, and to tease out the threads of my more recent meditation on one of the canon’s more intriguing minor characters, Louisa Wogan. Inevitably time passes and the old installments fall out of date—we have moved on from the 100th anniversary of Joyce’s Ulysses to the 100th anniversary of Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, and it would take some doing to draw a connection from Bloomsbury to the Royal Navy. Or would it? We must never forget the Dreadnought Hoax of 1910—the very year Woolf claimed that “human character changed”—when Virginia Stephen (as she then was), her brother Adrian, the painter Duncan Grant, and two others put on blackface and robes to pose as an Abyssinian delegation wishing to visit HMS Dreadnought, the Royal Navy’s newest and most modern battleship. The hospitable but credulous tars welcomed them aboard, hoisting the flag of Zanzibar when an Abyssinian flag could not be found. Virginia and the others spoke a gibberish compounded of Latin and Greek, shouting “Bunga Bunga!” to show their appreciation of the tour. Later, during the First World War, the Dreadnought rammed and sank a German U-boat, and was congratulated with a telegram reading “BUNGA BUNGA.” Terribly racist, of course, but also terribly funny.

Virginia Woolf’s little adventure aboard HMS Dreadnought may seem to have little to do the canon, but we mustn’t forget how often Stephen Maturin disguises himself or is taken to be of a different race or ethnicity. In a sense, he is always in disguise—think of how often he endures insulting language about Irishmen or Catholics from people who do not suspect they’re talking to one. He frequently works undercover, assuming the guise of a simple physician or naturalist with no political opinions whatsoever. Then there’s the deeply moving moment from HMS Surprise when a grief-stricken Stephen is accepted as an Indian, one of the child Dil’s caste, after her death. There’s comedy too, of the sort Virginia Woolf might appreciate, as in Post Captain when Stephen disguises Jack in a bearskin and himself as its trainer. “Remember the bear!”

Anyway, none of this has anything whatsoever to do with Desolation Island, one of my favorite novels in the canon for its action, its grueling feats of endurance, and the Stephen-Wogan-Herapath triangle. Enjoy what I had to say about it below—and as always, keep an eye open for spoilers. —JC 8/27/25]

1

As we prepare to set sail once more, departing from the vicinity of the new-and-improved Ashgrove Cottage for a voyage to the far side of the world, let us pause to salute, as many others have done, the one hundredth anniversary of the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the novel to end all novels, a work of high modernism in which nothing much happens. Joyce’s masterpiece would seem to offer a very different set of pleasures from O’Brian’s historical fictions. Yet of course Joyce’s hero, the mild-mannered Leopold Bloom, is based upon Homer’s Odysseus—the archetypal wandering sailor. And Joyce’s purported ambition in Ulysses to “give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book,” which speaks to the extremity of authentic detail he sifts into his novel, is perhaps not so different from O’Brian’s power to transport the reader to what seems a fully living Georgian England (and Mediterranean, and America, and India, et al).

O’Brian is above all a storyteller—”the best Yarn-Spinner in the all the Fleets”—and his heroes take part in suitably heroic and swashbuckling actions. By contrast the heroic-epic framework upon which Joyce so lovingly frames his novel’s non-events is fundamentally ironic in its effect. Yet Joyce’s mock-heroic narrative, over the course of hundreds of pages, has the peculiar effect of enlarging his hero rather than diminishing him. He gives us the whole man—Bloom in the outhouse, Bloom the anxious cuckold, Bloom the fantasist, Bloom the grieving father, Bloom the indifferent businessman—and so elevates his humane unheroism, as Milton in Paradise Lost gradually elevates Adam in his nakedness over the more glamorous and charismatic figure of Satan.

“Let us not be pedantic, for all love,” says Stephen to a new shipmate in Desolation Island. Merve Emre’s recent New Yorker essay, “The Seductions of Ulysses” describes how Joyce’s extremes of erudition force a kind of ecstatic humility upon the reader: we can never master, as Joyce apparently has, so many languages, so many references, so many symbols and layers. Love, Emre writes, is what Ulysses is fundamentally about, and the key to enjoying it is the relinquishing of mastery. Emre could be speaking of the Aubreyad when she writes of the essential mystery of Joyce’s language—how its gestures toward greater and greater precision are best experienced aesthetically, “an invitation to rub up against the sound-images, vowels and consonants dilating luxuriously over time.”

We must accept a similar invitation if we are to enjoy the dizzying layers of language—sea terms, Linnaean classifications, bits of French, periodic syntax, literary references, musical references—in which O’Brian immerses us. The alternative—no less pleasurable in its way—is to become pedantic: to settle down with the various multiplying reference works, to pore over the memoirs of Lord Cochrane, to argue on message threads, to listen attentively to the dissections offered by Mike and Ian and their guests on their delightful podcast, The Lubber’s Hole. I present these as polar alternatives, but there’s nothing to stop a reader from journeying from one pole to the other and back again, bathing in O’Brian’s language during one reading, then returning later to the same volume to track every allusion as relentlessly as the captain of the Waakzaamheid track the HMS Leopard through the Antarctic Ocean.

But I’m getting ahead of our story.

2

Desolation Island, like the preceding volume, begins with the arrival of Stephen Maturin at Ashgrove Cottage—this time, however, instead of finding its inhabitants penurious, Stephen discovers that the cottage is in the midst of being transformed into something more like a manor, thanks to the wealth Captain Aubrey acquired during the Mauritius campaign. The squalor of the half-pay captain’s overcrowded home has been supplanted by squalor of another kind—construction materials, expensively overbred horses, gaming for high stakes with Admiralty men who could make or break his career, and the schemes of a “projector” who proposes by means known only to himself to turn the lead dross on Aubrey’s land into silver. It’s time for Captain Aubrey to get himself to sea once again, before high living and a credulous nature can leave him and his exasperated wife houseless and penniless. But this time, Stephen Maturin does not arrive with a deus ex machina to rescue his friend from ignominious poverty. This time, Stephen is the one who needs rescuing.

We’ve seen Stephen at low points below—in H.M.S. Surprise he went from one disaster to the next, culminating in Diana Villiers’ abandonment of him in favor of a wealthy American named Johnston (or is it Johnson?). In The Mauritius Command he got a bit of his own back, using his skills as an intelligence agent to turn the tide against the French in the Indian Ocean; but we also learn that Stephen’s intelligence work is just about the only thing keeping him attached to life. His delight in natural philosophy has waned; he is unlucky in love; and in the first chapter of Desolation Island we learn that his efforts to medicate himself with the alcoholic tincture of laudanum are beginning to take a toll on his professional abilities. He has left secret papers in a coach, an unforgivable blunder; he lost a surgical patient, a young man he valued, to a laudanum haze. The return of Diana Villiers to London momentarily revives him, but when he seeks her out, he finds that she has abandoned him once again, this time for America. Not only that, but she’s been associating with an American spy, a young woman named Louisa Wogan whom everyone but Stephen sees as the spitting image of Diana. Even Sir Joseph Blaine, the spymaster who values Stephen’s work and thinks of him as a friend, is beginning to think that the diminished Maturin may have outlived his usefulness. He gives him, in effect, one last chance. Mrs. Wogan has been sentenced to transportation to Australia; she will be transported on a ship captained by Aubrey, and Stephen will accompany her and ferret out her secrets. Stephen understands that he’s being gotten rid of, but there is no other choice. Will traveling with the alluring Louisa Wogan renew Stephen’s appetite for life? Or will be succumb to the addiction with which he suppresses that appetite?

But these aren’t the questions I really wanted to ask.

3

Religion, Marx says, is the opiate of the masses, but nowadays, opiates are the opiate of the masses. People are hurting, and they respond to the hurt with drugs: OcyContin, fentanyl, heroin. The greedy and feckless actions of families like the Sacklers and the pharmaceutical companies that care only about profit are mostly to blame for this, but in our puritanical and punitive society, there is still a great deal of shame and ignominy associated with addiction. Perhaps now that more white people are suffering, we will begin to cut against our own grain—which has largely consigned and criminalized addiction as the province of people of color—and begin to show more compassion to addicts, responding to their plight with treatment instead of incarceration. Perhaps.

But that wasn’t the question, either. This is the question that Desolation Island and the slightly insane project I’ve set myself of writing about every single Aubrey-Maturin book has lodged in my mind: Am I addicted to these books?

Probably.

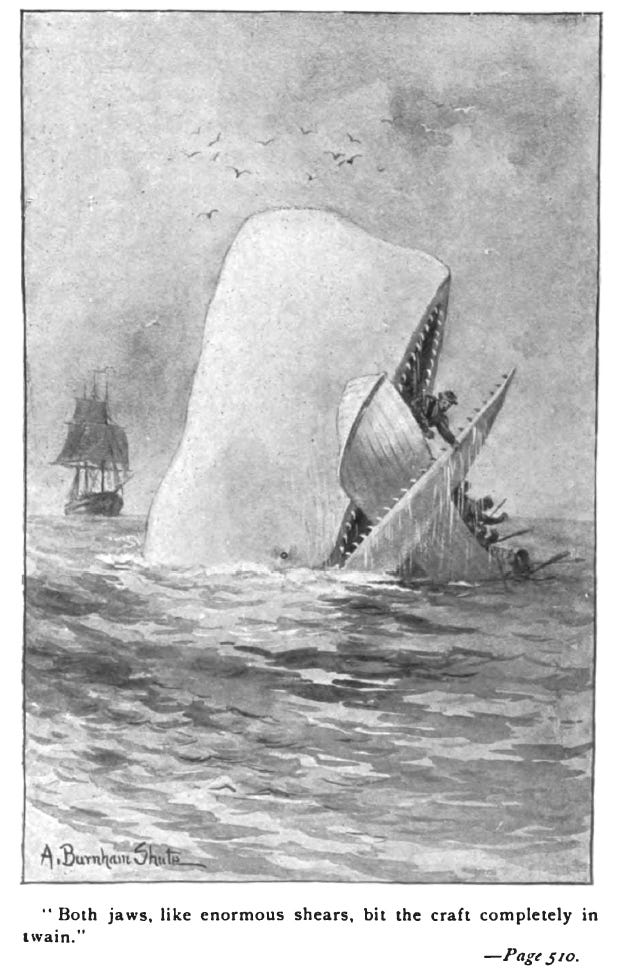

I am probably just like Ishmael, in this famous sentence from the famous first paragraph of the most famous of all novels: “Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

This, Ishmael adds, is his substitute for pistol and ball. He might as well have added: and for the alcoholic tincture of laudanum.

When the world is too much with me, and the mask I must wear to teach in grows too tight about the mouth; whenever the gray continuity of winter days surround me like lone and level sands stretching far away; whenever I find myself pent up in my apartment doomscrolling or twitching in front of old episodes of Cheers; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from getting into my car and leaving my family and running for the border, any border—then, I account it high time to pick up a volume of the Aubreyad and return metaphorically to sea.

Far more harmless, you may say, to read and obsessively reread a stack of sea stories than it would be to resort to actual drugs. But what is at the heart of our pity for the addict, or our condemnation? Is it the nature of the substance or substances to which they are addicted, one of an every-increasing list: alcohol, drugs, gambling, sex, smartphones? Or is it the compulsiveness of the behavior, whatever its object, and the tendency to use that object as a substitute for more fundamental human needs, like the need for connection with other people, and with oneself?

Am I addicted to Patrick O’Brian? To his endlessly varied and toothsome language? To the decorum and fierce liveliness of the early nineteenth century? To descriptions of ships and seas? To identifying a bit too closely with the most brilliant, acerbic, deeply learned, passionate, possibly slightly autistic and lovelorn landlubber ever to get to sea?

“Any innocent pleasure,” remarks Stephen Maturin in Post Captain, “is a real good: there are not so many of them.” Surely there is no more innocent pleasure than to be found in books, especially books so richly laced with erudition, the pursuit of which provides another entire layer of pleasure underneath the pleasures of character and adventure and poetry? Still I wonder.

Throughout Desolation Island we see Stephen struggling more or less openly with the addiction that threatens his ruin. The beginning of the chapter finds him resolving to go cold turkey, throwing his bottle of laudanum out the window of the coach carrying him to London. But at his next stop he visits an apothecary to buy some alcohol in which to preserve one of his ghoulish medical trophies, a pair of hanged man’s hands, adding, “While I am here, I might as well take a pint of the alcoholic tincture of laudanum.” On the first part of the voyage of “the horrible old Leopard” to New South Wales, Stephen is unusually harsh and snappish, apologizing at one point to Aubrey: “I am abandoning a course of physic, an injudicious course, perhaps; the effect is not unlike that produced in your confirmed tobacco-smoker when his pipe is taken from him, and sometimes, alas, I yield to fits of petulance.” But how complete is his abandonment? Shortly before this interview, Stephen discovers a cache of laudanum in the medical supplies allotted to the prisoners H.M.S. Leopard is transporting: “‘Vade retro,’ he cried, seizing the nearest and opening the scuttle: but after the first had gone he paused, and in reasonable, false, considering voice he observed that what was left should be preserved for the use of his patients; there were many contingencies in which the tincture might be of essential consequence to them.”

Get thee behind me, Satan! Laudanum is not Stephen’s white whale; that honor goes to Diana Villiers, if it goes to anything besides actual whales (Stephen has a quasi-religious encounter with a blue whale late in the novel). But laudanum eases the pain of his pursuit—of the uncertain connection he feels to the woman whose grace and ease of movement he finds so bewitching. Perhaps too laudanum eases the pain of daily contact for an intensely private man cooped up with three hundred or more other men in a vessel 146 feet long and just 40 feet wide. It separates him from reality, enough to make it bearable; but, as Dr. McAdam remarked in The Mauritius Command, it cannot preserve a man who has passed from needing protection from the pain of desire to someone who has lost his capacity for desire altogether.

4

Fortunately for Stephen, and for the analogy I’m trying to draw, there is another approach to narcotics as presented by the character of Michael Herapath. Just as the intrepid Louisa Wogan is likened to Diana “but on a smaller scale,” Michael Herapath, an admirer of Louisa’s who stows away on the Leopard to be close to her, is a younger and more ingenuous version of Maturin: a scholar (of Chinese poetry, not of birds) with medical aptitude driven by his hopeless desire for a woman who might at times reciprocate his desire but who can never love him as he would wish to be loved. And Herapath, like Maturin, self-medicates with opium. As befits a man who has studied in China, however, his preferred means of taking the drug is to smoke it. He informs the astonished Maturin that he has reached a kind of accommodation with opium, a middle path between addiction and abstinence. “At present,” he tells Stephen, “I can look upon my pipe with a mild, affectionate regard; it is no longer the malignant, evil, necessary monster that once it was; and I take it – or should I say I took it, since it is now some five thousand miles away – from its place perhaps once a week, like the mechanic with his beer-can, for mere pleasure, or when I needed strong waking endurance for some unusual task or relief in a rare emergency.”

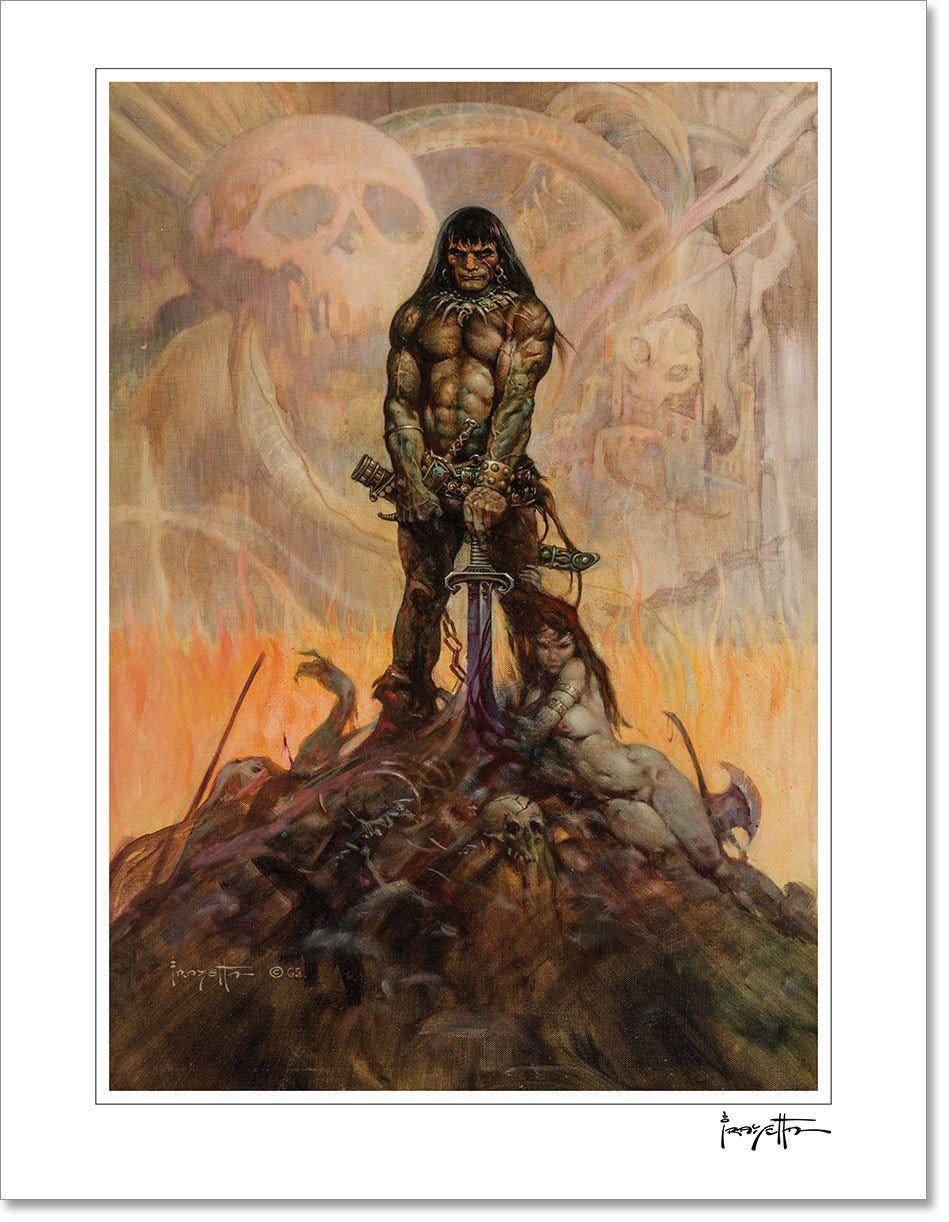

Jason Ray Carney has written an article with the arresting title, “Reading Sword-and-Sorcery to Make the Present Less Real.” In it he points out how literary fiction is often presented by its advocates as “prosocial,” bringing readers into closer contact with others and with reality thanks to its stimulation of our empathic capacities. (I confess, as a literature and creative writing professor, to thinking and teaching something similar to my students.) He follows this up with the counter-intuitive claim that pulp and genre fiction—Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian stories are his chief example—attract readers not by immersing them in a vivid and detailed alternative world, but by understimulation: these books are “mental oases to insulate our sensorium from the present.” And he’s right: no matter how rich and vivid the adventures or worlds such stories describe, they will be far simpler, far more digestible, than any given hour in our actual lives.

Carney describes such fiction as “an inoculation against an illness-inducing reality,” pointing out that Howard published his first Conan story in 1932, one of the direr years in world history. But this inoculation does not function as old-fashioned non-mRNA vaccines do, by stimulating the immune system with a manageable fragment of infection; it is more like an opiate. To be on the nod, as William S. Burroughs described it, is to be freed from any need for stimulation whatsoever; he could stare at his own shoes for eight hours after shooting up. Opium dens and shooting galleries aside, it’s a profoundly antisocial high. And so, of course, is reading. We are always alone when we read a novel, unless we force it into another register by reading it aloud to someone else. It is a strange sort of intimacy, of disconnected connection. Patrick O’Brian has been dead for many years now, and O’Brian isn’t even his real name! Yet I feel a connection with him that is deeply intimate; and were he alive—as I know from my encounters with other writers—I know that we would connect far less well in person than I do with his voice on the page.

Carney, admirably in my view, does not attempt to redeem the fundamentally antisocial quality of the pulp fiction he loves as secretly prosocial, as making him somehow “better.” “Perhaps like prayer or meditation, sword-and-sorcery — and escapist fiction more generally — is a form of self-negation, of transcendence,” he writes. “Justifiable or not, it is a modern attempt to make the present less real.” What fills the evacuated present besides images of Conan the reaver, or Captain Jack? Nothing and no one. When we read genre fiction, Carney seems to say, there is no “I.”

5

We call this kind of fiction “escapist.” Escape from what, and why? Is genre fiction a vacation? A reprieve? Having absented ourselves from our illness-inducing reality—in the case of COVID, we could call it a literally ill reality—does reading genre fiction return us to the real world refreshed, better able to deal with our problems? Or does it leave us, as excess of laudanum has left Stephen at the opening of Desolation Island, even less equipped than we were before, dangerously out of touch with ourselves, with our passions, and with the people we say we love?

I suppose I take my Patrick O’Brian as Michael Herapath takes his opium pipe, as something he can take or leave. At least that’s what he, and Stephen, and I, desperately want to believe. In the meantime I have these essays, and Mike and Ian, and the knowledge that to read and reread these books is to engage in a kind of parallel play with the thousands upon thousands of other readers who have loved them. Actual contact would break the spell. Wouldn’t it?

The great set-piece of Desolation Island is the days-long duel with the Waakzaamheid, a Dutch 74-gun ship of the line that relentlessly pursues the Leopard through the far southern seas, probably—though we never know for sure—because in repelling its initial attack, Jack’s men may have killed one of the Dutch captain’s relations. The pursuit is like a nightmare: whatever maneuver Jack conjures, he is unable to shake the Dutchman, and the pursuit leads him into rougher and rougher seas, until they have reached a point where the least accident to a sail or mast could cause one ship or the other instantly to founder. It’s one of the tensest and most memorable scenes in the entire series, as Jack takes personally to firing the stern-chaser cannon out of his own cabin at the pursuing Waakzaamheid, “twenty yards away, huge, black-hulled, throwing the water wide.” Jack has been wounded in the head, put into a fog that separates him from the terrible reality of a ship that skates along towering waves an inch from destruction, yet still he helps to run out the gun, though he is too slow to react when it fires and the recoil flings him to the deck. “But for a moment he could not understand the cheering that filled the cabin, deafening his ears: then through the shattered deadlights he saw the Dutchman’s foremast lurch, lurch again, the stays part, the mast and sail carry away, right over the bows.”

The Waakzaamheid goes down and Jack is stunned. “‘My god, oh my God,’ he said. ‘Six hundred men.”

Am I truly “understimulated” by such an episode? Does my immersion in Jack’s valor and terror dull my senses? Does following the perambulations of Leopold Bloom through his ordinary Dublin day somehow sharpen them? Suppose I read for the erudition of either author, as so many of their readers do, hunting for allusions, historical tidbits, multilingual puns, etc.?

I’ve read these books so many times, but I feel like I know longer know where they are taking me. It’s a voyage into reading, that’s clear. Into the deep experience of reading itself, what it’s for, what it’s meant to me.

By the end of the novel the Leopard is barely intact, stranded on the island that gives the book its title, dependent on one of Stephen’s stratagems to persuade the crew of an American whaler to loan the English man-of-war its forge so that a new rudder can be fitted to the crippled ship. He pulls it off, and a major intelligence coup as well. The book ends on the alluring laugh of Louisa Wogan, with “a fine triumphant ring.” It is Stephen’s triumph, all along.

It’s far from clear to me whether, by novel’s end, he has kicked his habit, or not.