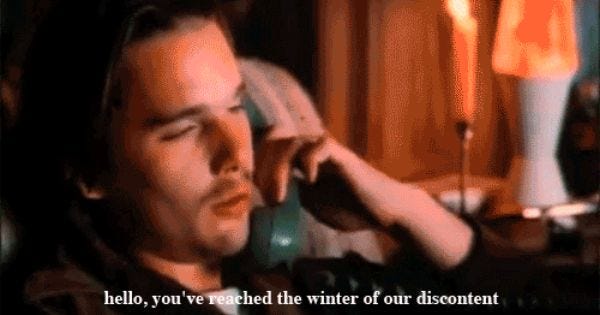

The new issue of Harper’s, which I failed to find at my local newsstand yesterday, is devoted to the question, “What Happened to GenX?” My favorite Substacker, Justin Smith-Ruiu (b. 1972) wrote the lead story, but it’s paywalled, so instead I turned to Adam Kirsch’s (b. 1976) GenX-centric review-essay “Come as You Are.” Our g-g-generation, Kirsch says, came to consciousness at the so-called “end of history,” skeptical of utopian projects or of any project other than cultivating the self—and even that project was thick with the thorns of a necessary skepticism. Whatever was our war cry in the face of a materialism too crass not to be a lie; never sell out was our mantra. Sulky Ethan Hawke (b. 1970) and mopey Winona Ryder (b. 1971) taught us to never trade the imperfect for the goods.

I (b. 1970) was as shaped by these attitudes as anyone, along with a nagging sense that history had both passed me by and had shaped my destiny in ways I would probably never understand. My mother’s parents were in the concentration camps and she herself hidden as an infant in the Budapest ghetto; after the war she spent a few difficult years in a displaced persons camp before emigrating to America and a new life in the Bronx. That history was in my bones long before I knew how to name it, vibrating strangely in the sterile landscape of Reaganism that presented my generation with the terrible binary of 1=mindless consumerism / 0=nuclear annihilation. The fall of the Soviet Union coincided, in 1991, with my mother’s premature death from cancer. I was unable not to see her withered, hairless, bony body as a kind of Mussulman, the bare life revealed by the camps in which her parents, my grandparents, had been imprisoned. A visible legacy, an epigenetic specter that haunts me still.

From this perspective it’s no wonder that I was unable to embrace fiction, with its imperial demand that the writer as well as the reader suspend their disbelief in the made-up scenario. Fiction was too definite for me. My first attempt at a novel failed—it was about an alienated grieving adolescent’s obsession with the life and death of Freddy Mercury—the embodiment of contextless operatics feeling (c.f. the baroque meaninglessness of “Bohemian Rhapsody”—at this time I had no awareness of the former Farrokh Bulsara’s Parsi-Indian ethnicity, his own embeddedness in a Gordian knot of colonial migration and self-fashioning. One of these days I need to write something about my love of prog rock, particularly Jethro Tull, with lyrics nearly devoid of semantic content yet completely evocative, an invitation to dream. But this digression has gone on long enough).

I turned to poetry as the only means of written expression that foregrounds the activity of language as an instrument of perception prior to whatever world or objects the poem pretends to perceive. Poems don’t create a context for themselves; they are embedded in what the reader already knows or doesn’t know about that poet’s biography and the time of writing (that’s why the dates appearing after each poem in, say, the Norton Anthology of Poetry have such potency).

There’s also the fundamental GenX value of “openness” that Kirsch talks about. I’m the kind of guy who can rarely take his own side in an argument; I used to think it was because I’m a Libra, but now I recognize it as potentially a generational trait. Poetry felt like the solution to the problem of expression, because what it says in one line it can unsay in the next. The magic of poetry was the mental movement that came from the oblique turns and odd angles (angels?) of enjambment that complicate or disable anything like simplicity of statement. That’s why John Ashbery remains for me the paradigmatic poet, who asks that his reader stay with the movements of his mind, its rhythm, and whose poems are so utterly unparaphrasable. Ashbery (b. 1927) belonged to the Silent Generation, but in his wry obliqueness he’s the quintessential GenX poet. One of my favorite Ashbery poems:

The History of My Life

Once upon a time there were two brothers.

Then there was only one: myself.

I grew up very fast, before learning to drive,

even. There was I: a stinking adult.

I thought of developing interests

someone might take an interest in. No soap.

I became very weepy for what had seemed

like the pleasant early years. As I aged

increasingly, I also grew more charitable

with regard to my thoughts and ideas,

thinking them at least as good as the next man’s.

Then a great devouring cloud

came and loitered on the horizon, drinking

it up, for what seemed like months or years.

Most of the poems in my now-twenty-year-old first book, Selah, were written in the late nineties, when “history” took the debased form, in America, of cum stains on a blue dress and a celebrity murderer’s late-night McDonald’s runs. “Selah” is a liturgical word from the Hebrew psalms with no certain meaning; it could be a notation that the speaker or singer of the psalm is to “lift up” their voice, or it could simply indicate a pause. A word that derives its meaning entirely from its context, in other words; a ritual signifier of ritual itself. That’s how estranged I felt myself to be from anything like a common language by which I might express who I was or how I felt, since I was a secular Jew with only the most distant relation to the actual singing of psalms or the recitation of prayers. The history in the poems is my mother’s history, my sense of her as one of Hitler’s victims, and of whom I myself was something of a victim. The book begins with a parodic translation of Paul Celan’s “Psalm,” a poem that takes the form of a prayer to no one, a poem about the impossibility of praying in the face of God’s silence in the years 1939-1945. Here’s Celan’s original:

Psalm

Niemand knetet uns wieder aus Erde und Lehm,

niemand bespricht unseren Staub.

Niemand.Gelobt seist du, Niemand.

Dir zulieb wollen

wir blühn.

Dir

entgegen.Ein Nichts

waren wir, sind wir, werden

wir bleiben, blühend:

die Nichts-, die

Niemandsrose.Mit

dem Griffel seelenhell,

dem Staubfaden himmelswüst,

der Krone rot

vom Purpurwort, das wir sangen

über, o über

dem Dorn.

John Felstiner’s translation:

Psalm

No one kneads us again out of earth and clay,

no one incants our dust.

No one.Blessèd art thou, No One.

In thy sight would

we bloom.

In thy

spite.A Nothing

we were, are now, and ever

shall be, blooming:

the Nothing-, the

No-One's-Rose.With

our pistil soul-bright,

our stamen heaven-waste,

our corona red

from the purpleword we sang

over, O over

the thorn.

And the homophonic translation that starts my book:

Psalm

Neiman Marcus knits a leader out of earth and lime.

Neiman beshops a western stab.

Neiman.Galloped apts do, Neiman.

Dear zoo leads woolens

to veer bloomers.

Dear

engager.Nine naughts:

where we’re singed, we’re wared,

we’re weary bluehound.

Deathnaut dreading

kneeled man’s rose.Mid-

den grin seals in hell

dem stabled-faded him’s liverwurst,

dares crone’s rot.

Vow the pupa’s word. Dazzled weresong.

Or bear, O you bar

the door.

Puerile yet genuinely haunted—back then that was my poetic sweet spot. I started submitting the manuscript to contests in 1999 or 2000; it won the Barrow Street Book Prize (judged by fellow New Jersey Jew Robert Pinsky) in 2002 and was published in 2003. In between time, history returned with a vengeance. I was a few weeks shy of my thirty-first birthday on 9/11, and my reaction was one of disbelief. On some primordial level, I’ve been unable to credit what’s happened in the world since that time—the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the 2016 election of a man anyone from the Tri-State area knew was a criminal buffoon, the pandemic, the climate crisis. It’s not that I deny the reality of these events, it’s just that they lack the power to shape my character the way the atmosphere of the 70s and early 80s did. The Obama years were the exception, a kind of historical time-out; if America was finally ready for a Black President, maybe History had ended in the right way after all. Of course, we weren’t ready, and the naked virulence of the post-Obama backlash makes me wonder if we ever will be.

My third book, Severance Songs, came out in 2011 and was the product of the curious intersection of a pastoral period in my life (moving to Ithaca, New York, getting a PhD, a process I found perfectly enjoyable, meeting and marrying my wife) with the depredations of the Bush-Cheney regime. The poems in that book—mostly fractured and unrhymed sonnets—try to negotiate the intersecting landscapes of love and disaster. My next collection, The Barons, was my most explicitly political book to date—the title poem is an incantatory condemnation of the spirit of greed that no longer bothers to cover itself with even half-convincing lies. But it didn’t seem to resonate much with readers. The full-throated sincerity of Millennials is not, it seems, my mode. As I grow older, I am increasingly out of step with what seems to be the dominant poetic consciousness, which centers on present-tense representations of identity as transfixed by history. I don’t doubt the importance of such writing, but it doesn’t suit the GenX sensibility which I reluctantly admit to be mine.

So what do I and the other writers of my marginalized generation have to offer? There are major writers in our cohort, as Kirsch affirms: Zadie Smith is his paradigmatic example, and her newest novel, The Fraud, makes the leap from the “hysterical realism” of her early work to historical fiction. History, it seems, is the last refuge of the older writer, who can no longer be trusted to give or get the news about what’s happening now—maybe more importantly, older writers aren’t native speakers of the extremely online language of the present. Even a younger writer like Tricia Lockwood, whose novel No One Is Talking About This is one of the best renderings of the online sensibility that I’ve encountered, is probably too removed from TikTok discourse to capture what, in W.S. Graham’s words, the language is using is for in 2023. My own attempts at fiction have blended the historical and autofictional, so as to speak from the historical (hysterical?) forces that have shaped my experience.

Autofiction is arguably the most poetic form of fiction, because it depends for its effect on the reader’s understanding of the slipperiness of the story, which is both true and not true, as the protagonist both is and is not the writer whose name Is on the cover. It’s the logical narrative form for a generation raised to distrust grand narrratives, or any narrative that depends upon its author’s supposed authority over any material other than their own lived experience. The separate components of the narratives of my novels exist in tension with each other the way each line of a poem partially negates the line that preceded it. That makes them poets’ novels in a rather literal way.

My first two novels were about the persistence of twentieth-century history and its power to shape or thwart the fortunes of its post-historical protagonists. Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy is a kind of noir fantasia about a young mother haunted by the spirit of her Holocaust-survivor mother, who dreams up a detective story about that mother’s participation in the May 1968 student revolts in Paris. My second novel, How Long Is Now, is more overtly autofictional, juxtaposing the European travels of its troubled writer-protagonist in the wake of his father’s paralyzing accident with a reconstruction of his parents’ courtship in 1960s New York. Both novels betray my obsession with “the greatest decade in the history of mankind,” and with the Holocaust, and how they might have informed the character and expectations of someone b. 1970.

I have moved on from this ground in my more recent, as yet mostly unpublished work. From personal history and capital-H history I’ve turned to future history with a loose trilogy of science fiction novels, currently on submission to publishers. My current project is straight-up historical fiction, though not entirely un-autofictional, since I have a family history connection to the main character, the Jewish boxing champion, war hero, and reformed drug addict Barney Ross. My thinking about that book has been helped enormously by the recent Paris Review interview with the poet and fiction writer John Keene, whose Counternarratives did a lot to shake up my notion of how fiction might engage with history and also with itself. The very title suggests something of the self-negating or at least dialectical relationship between components of a story that I’ve derived from poetry. (Born in 1965, Keene is on the cutting edge of a GenX sensibility, as captured by this remark from the interview: “I say this not to criticize writers, but since the early two thousands there has been a shift to people deciding that they want to be a brand. We have crossed the neoliberal Rubicon.”) The book as it takes shape presents multiple voices and fragments of stories that will, I hope, create something close to the expansiveness and resonance that Keene achieves in Counternarratives—the rare story collection with the heft of a novel, or perhaps even greater heft than the majority of novels achieve.

What’s the deal, Corey—nothing for nearly three months, and now two posts in a single week? What can I say? The Rarebit Fiend’s dreams run on no schedule but their own.