(N.b.: I began writing this post nearly three years ago and then got distracted and put it aside. I post it now, partly because I haven’t posted for a while [I’m three weeks into the new semester and the time not devoted to teaching and family life has been devoted to the novel I’m writing], partly because I’m still interested in the stances and assumptions of My Generation and what we can offer to a culture that seems in so many ways to have passed us by. See what you think.)

Two recent essays take on a literary phenomenon that unites the present and the posthumous. David S. Wallace’s “Dead Poet Anxiety: John Ashbery in the Age of Social Media” considers the first (but no doubt far from the last) posthumous publication by the pre-eminent poet of the postwar American era, Parallel Movement of the Hands: Five Unfinished Longer Works. At roughly the same time, Stephen Marche published an essay with an even more cumbersome title: “Winning the Game You Didn’t Even Want to Play: On Sally Rooney and the Literature of the Pose.” Somewhere between these two essays, and their consideration of what it means to write, now, between the poles of “voice” and “pose,” poetry and fiction, lurks a subject of intimate concern. How should a writer be? How should this writer, in particular, be in a historical moment in which the meaning of one’s identity as a writer seems so precarious, so very much up for grabs?

Marche’s essay surveys the past sixty years or so of Anglo-American fiction, drawing a distinction between the Boomer-dominated “Literature of the Voice” (Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy, Martin Amis, and especially Philip Roth are his exemplars of this mode) and the Millennial-sponsored “Literature of the Pose” (defined by Rooney and her outsized success, but Marche also name-checks the likes of Ottessa Moshfegh and Ben Lerner, as well as a couple of derisory ringers like Rupi Kaur).

Marche is six years younger than me, but that still fits him comfortably inside the uncomfortable envelope that is Generation X, and so we can be pretty confident, even before he starts denigrating the often flavorless prose, that “Literature of the Pose” is derogatory and not a neutral descriptor. “Poser” was one of the most cutting and often-flung insults of our youth, right up there with “sellout.” But he’s hard on our parent’s generation as well, offering this brilliantly backhanded compliment to Philip Roth:

Philip Roth has the most delicious voice because the limitations of his empathy are so extreme. He is a Jewish man from Newark. No other perspective makes sense to him and he expends little to no effort trying to make sense of what others might feel or think. In The Human Stain, Nathan Zuckerman dreams of Bill Clinton’s persecution: “I myself dreamed of a mammoth banner, draped dadaistically like a Christo wrapping from one end of the White House to the other and bearing the legend A HUMAN BEING LIVES HERE.” It never occurs to Roth, not even as a passing thought, that the women in the White House might be human beings too.

Marche contrasts the project of Roth and other Boomer/Voice writers with that of modernists like Faulkner, “for whom the fluidity of voice was grand strategy… The immense variety of modes in James Joyce or Vladimir Nabokov or Virginia Woolf are dreams of the escape into multiplicity.” But one could never mistake the prose a member of our grandparents’s generation or that of the Boomers for that of any other member. Marche is at pains to demonstrate that the prose of the Pose, of Millennial (and younger) writers, is one indistinguishably flavorless broth. He argues that for younger writers, anxiety about correctness—it isn’t even political correctness, necessarily, just a terror of gaucherie raised to an existential level—has led to a writing whose anonymity on the level of style is proportionate to the nakedness of the author’s self-revelation. “The style grows less personal even as the auto-fictional content grows more confessional,” Marche writes. “The more prominent the writer, the less individual the style.”

Rooney and her success offer the most extreme example of the pitfalls of coming to consciousness as a novelist in the glare of the social media spotlight, in which the commodification of the author becomes the content of the work—cue the bucket hats. Poets are not immune from this cycle of commodification: Marche and Wallace both single out inaugural poet Amanda Gorman as an avatar of the Pose. Marche notes that the yellow coat Gorman wore at Biden’s inauguration led to a modeling contract and concludes, “The first thing a young poet needs to be heard today is not mastery of language nor the calling of a muse. It’s a look. The writing of the pose is the literary product of the MFA system and of Instagram in equal measure—it brings writing into the ordinary grueling business of the curation of the self which dominates advanced capitalist culture today.” Wallace remarks that “Gorman supplements the banality of her verse (the ‘hill we climb,’ the title of her inaugural poem and, now, her first book, is only another dilution of King’s ‘the arc of the moral universe is long,’ a sentiment already pulverized by the Obama era) with an immaculately packaged social media persona.” It’s perhaps not the best look for a couple of white male critics to appear to be dissing a young Black woman, though I think that for both critics she is a symptom and not the cause. Marche at least is highly sympathetic to the dilemma in which the pure products of mediated America find themselves. The poems that are the most Instagram-friendly tend to be simplistic affirmations of identity, byproducts of the persona that is the Instapoet’s real work and product. The poem functions as merch, a parasocial glint of reflected glamor.

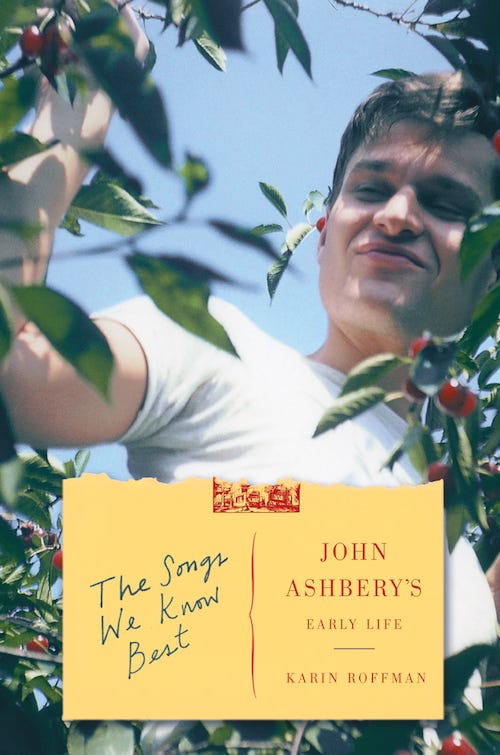

Marche’s focus is on fiction, the most prestigious literary mode of the 20th century—even brilliant essayists like James Baldwin and Joan Didion wished to be known as novelists—but I wonder how his sociological breakdown applies to a poet, a contemporary of theirs (and of Roth, et al) whose writing seems much closer to the logic of the Pose than of Voice. I’m thinking of course of John Ashbery, the most chameleonic of major poets, whose star, David Wallace suggests, is fading rapidly in a moment in which American poetry has pivoted toward “an assertion of identity and difference as a poetic subject and a more frank discussion about race and social justice.”

Ashbery is the odd man out because his poetics so perfectly upholds what Richard Hugo, in The Triggering Town, called the cynicism of the imagination:

The imagination is a cynic. By that I mean that it can accommodate the most disparate elements with no regard for relative values. And it does this by assuming all things have equal value, which is a way of saying nothing has any value, which is cynicism.

Hugo, who I think of as my first poetry teacher, even though I never met him, slyly updates the Keatsian idea of negative capability—less the “irritable reaching after facts” part and more the part about “the poetical Character itself”:

As to the poetical Character itself (I mean that sort of which, if I am any thing, I am a Member; that sort distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; which is a thing per se and stands alone) it is not itself - it has no self - it is every thing and nothing - It has no character - it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated - It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion Poet. It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity - he is continually in for - and filling some other Body - The Sun, the Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute - the poet has none; no identity - he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God's Creatures.

In today’s context, we might assign “the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime” to the poetry of identity, in which the poet speaks from a fixed position (or pose), for the purposes of enhancing the power of that pose, that thoroughly commodifiable objective self. A poet like Ashbery, on the other hand—probably the single most influential poet for my generation, in spite of having been born in 1927—evades the identiarian, focusing on a play of language that befuddles or delights the reader by suppressing the usual moral or political or indeed syntactic judgments of ordinary language. Popeye and the Sea Hag are no more or less important than the parodic pastoral setting in which Ashbery places them; to try to read “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape” for some sort of coded message about, say, Ashbery’s queer identity is to miss utterly the point.

Which is not to say that Ashbery himself was a cynic. As Hugo says a bit later in the same essay, anticipating the anxious reader’s question, “doesn’t this lead finally to amoral and shallow writing? Yes it does, if you are immoral and shallow.” Actually, I don’t know too much about Ashbery the man, and I don’t much need to know—what I enjoy and find enabling is the freedom of imagination he enjoys, his loyalty to the stuff of language, and the self-trust—the quality young artists are maybe most in need of, today—that enables him to trust that what he writes has value without his having to signal its virtuousness. “Don’t worry about morality,” Hugo assures us. “Most people who worry about morality ought to.” Put another way, the cynicism of which Hugo and Keats speak, in their different registers, is actually a measure of the idealism of any writer who trusts language to help them, in Hugo’s words, “locate, even create… your inner life.” Which is an affirmation of the inner life, innit? How old fashioned. How necessary! (And the real meaning of the Hugoism that used to adorn the brochure of the University of Montana MFA program, which is where I got my writing degree back in the day: “A poetry workshop may be the last place in America you can go where your life still matters.”)

Hugo and Ashbery were very different poets: Hugo was, frankly, a rank sentimentalist, as he would have been the first to admit, and as that line above would suggest. Hugo is warm and Ashbery is cool; Hugo wears his vulnerability on his sleeve and Ashbery’s must be inferred from the elusiveness of his lyric “I.” But they were both overwhelmingly interested as poets in where words might lead them—trusting that they would always lead back not to their egos but to their inner lives, as index of all that the inner life might contain, which includes one’s travails and one’s times.

I’ll give the last word to Tristan Tzara, who takes this attitude to its logical conclusion, tongue firmly in cheek:

To Make a Dadaist Poem

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are—an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.