I am still not quite ready to formulate my thoughts on The Hundred Days or to move on to the final completed novel in the Aubrey-Maturin series, Blue at the Mizzen, much less the final incomplete novel, 20. I am in a state of readerly melancholia at the prospect, unready to move on to the task of mourning demanded, quite literally in this case, by the death of the author. But I find myself spending a lot of time in the nineteenth century for work—one of the courses I’m wrapping up is a survey called Diverse Voices of Nineteenth-Century American Literature—and that means I’ve been spending a bit of time with two of my all-time favorite writers, Henry James and Ralph Waldo Emerson. I feel that I’ve discovered something, an illuminating metaphor, that explains my attraction to them both, and might even help me do a better job of teaching how to read them to my students on the next go-round. Let’s dive in!

Readers of Henry James have heard the cheeky quip dividing his output into three periods: James I, James II, and the Old Pretender. I’m fond of all three Jameses and see no need to choose between the masterworks of James I (The Portrait of a Lady), James II (The Aspern Papers, What Maisie Knew), and the Old Pretender (The Wings of the Dove, The Ambassadors, The Golden Bowl). In the week I can give to James, I ask the students to read two shorter works from the first and third periods, respectively: Daisy Miller (1879) and The Beast in the Jungle (1903). They like Daisy Miller, a lot. They’re a bit less sure of what to make of The Beast in the Jungle, though they ended up liking that story as well. Among other things, its portrait of a nameless anxiety that haunts a man his whole life seems to resonate with the Gen Z state of mind.

Daisy Miller is usually described as a novella of James’ “international” theme, but this is a bit more ambiguously the case than it is with The Portrait of a Lady or The American, both of which feature intelligent but naive American protagonists confounded by the perfidy of the Europeans with whom they become entangled. There are actually comparably few European characters in Daisy Miller; the only significant one is the cavaliere avvocato Giovanelli, the penniless young Italian friend of Daisy’s whom the other American characters suspect of being an adventurer. The divide is not between American and European in this novella so much as it is between tourist and traveler, or visitor and expatriate. Daisy and her family present as types of the ugly American, in spite of Daisy’s own much-insisted upon unspoiled beauty; Winterbourne, the American who has lived abroad since he was a boy, belongs to an expatriate community of Puritans who function collectively as the angry God into the hands of which the innocent Daisy falls.

American literature is mostly just sublimated Calvinism—that terrible anxiety that someone somewhere might be enjoying themselves (c.f.: Someone is wrong on the Internet!) which is the inverse of the belief that some power has judged us and found us wanting. Calvinist predestination, which speaks to what’s inside a person, can only be confronted externally; this is the logic of Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, by which anxiety about whether one has been predetermined for salvation or damnation manifests as the search for signs, the most consistently valuable of which is worldly success. As the American nineteenth century rolls along God, more or less done in by Darwin, gradually drops out of the picture, yet the Calvinist structure of feeling persists. The mostly unseen Europeans of Daisy Miller are like that Calvinist God, the infinitely remote bearers of a judgment from which there can be no appeal. Daisy’s innocent flirtation with every man she meets threatens to bring down shame on the American expatriate community, if not America as a whole; as a result the aptly-named Winterbourne freezes her out, and the melodramatic yet inevitable result is her death.

Not too much of this has anything to do with the style of Daisy Miller, which is eminently simple, clear, and readable. Each sentence is a bit of bedrock that develops character or advances the plot; each scene is consequential for the next; the story is neatly divided between two locations (Lake Geneva, Switzerland, and Rome), and the ending is a masterpiece of irony. Winterbourne, who was attracted to Daisy but unable to decide whether or not she was a “nice girl,” goes on at the end more or less as he was going at the start, in an ambiguous relation to his adopted home. He is either “studying” (the scare quotes are James’; he was addicted to them) or in some kind of relationship with “a very clever foreign lady.” Perhaps she is what he’s “studying,” but either way, the implication is that Winterbourne is a cold fish who, like so many of James’ characters, prefers the study of life to living it. (In fact, Daisy Miller is subtitled “A Study.”)

Fast-forward twenty-four years and we have The Beast in the Jungle, a novella in James’ late style, about a man, John Marcher, who never “does” anything in his life because he is convinced that something wonderful or terrible will someday happen to him, obviating the possibility of his choosing anything. He re-encounters a woman named May Bartram whom he’d met years before, and with whom he’d had the sort of ambiguous flirtation that was Winterbourne’s speciality, though he doesn’t seem to remember much about it. They become intimate without embarking upon anything resembling an ordinary relationship; certainly they don’t get married. Instead she agrees to “watch” with him for the extraordinary event—the titular beast in the jungle—that he is sure will one day spring. This goes on for years, and we never hear the characters discussing anything else, and indeed there are almost no other characters in the story! At last May becomes dangerously ill, but when they meet for the last time all they can talk about, as usual, is Marcher’s destiny. She dies; he’s bereft; he travels abroad for a year or so and then comes back to London and visits her grave, and then he’s really bereft. The beast in the jungle was, of course, his refusal to choose anything, and more particularly to choose May. (May signifies permission and also the heart of spring; Marcher evokes spring at its coldest and also a kind of blind, pre-ordered movement.) Oh, the irony, built atop what Edgar Allan Poe said was the most poetical of all events, the death of a beautiful woman.

But I am trying to get to style. Let’s compare the first sentences of these novellas. Daisy Miller:

At the little town of Vevey, in Switzerland, there is a particularly comfortable hotel.

A perfectly straightforward bit of scene-setting, yes? Almost a stock sentence; only the very slightly periodic syntax, delaying the verb and direct object to the final clause, strikes us as Jamesian. Adequately, sturdily, it prepares us for a conventional narrative, as comfortably delivered as the environs of the “particularly comfortable hotel” at which the first part of the story will take place.

Now here’s the opening sentence of The Beast in the Jungle:

What determined the speech that startled him in the course of their encounter scarcely matters, being probably but some words spoken by himself quite without intention—spoken as they lingered and slowly moved together after their renewal of acquaintance.

What’s that you say now?

With this complex sentence the Old Pretender casts the reader into the deep end. We struggle for orientation—who is the him and the they? Why are the first two linked clauses—”What determined the speech that startled him in the course of their encounter”—immediately canceled by the words “scarcely matters,” and then all but incinerated by the denigration of the “intention” of the “he”? The identity of the “they” in “they lingered” hovers ambiguously between the persons renewing their acquaintance and the unintentional, indeterminate “words spoken by himself.” Could it possibly be the words themselves that are renewing their acquaintance? We are left groping for sense, with very little solidity under our feet.

Practically every sentence in The Beast in the Jungle is like that: we are always in the middle of a complex series of actions and ideas. These create the notoriously hazy, blurry effect of late James, in which we seem as readers to be constantly trying to dispel the fog of the language to get at what the characters might actually be doing or thinking. Yet this linguistic fog, which so exasperates readers of more lucidly conventional narration, is a feature and not a bug of what I want to call the late James’ holographic style.

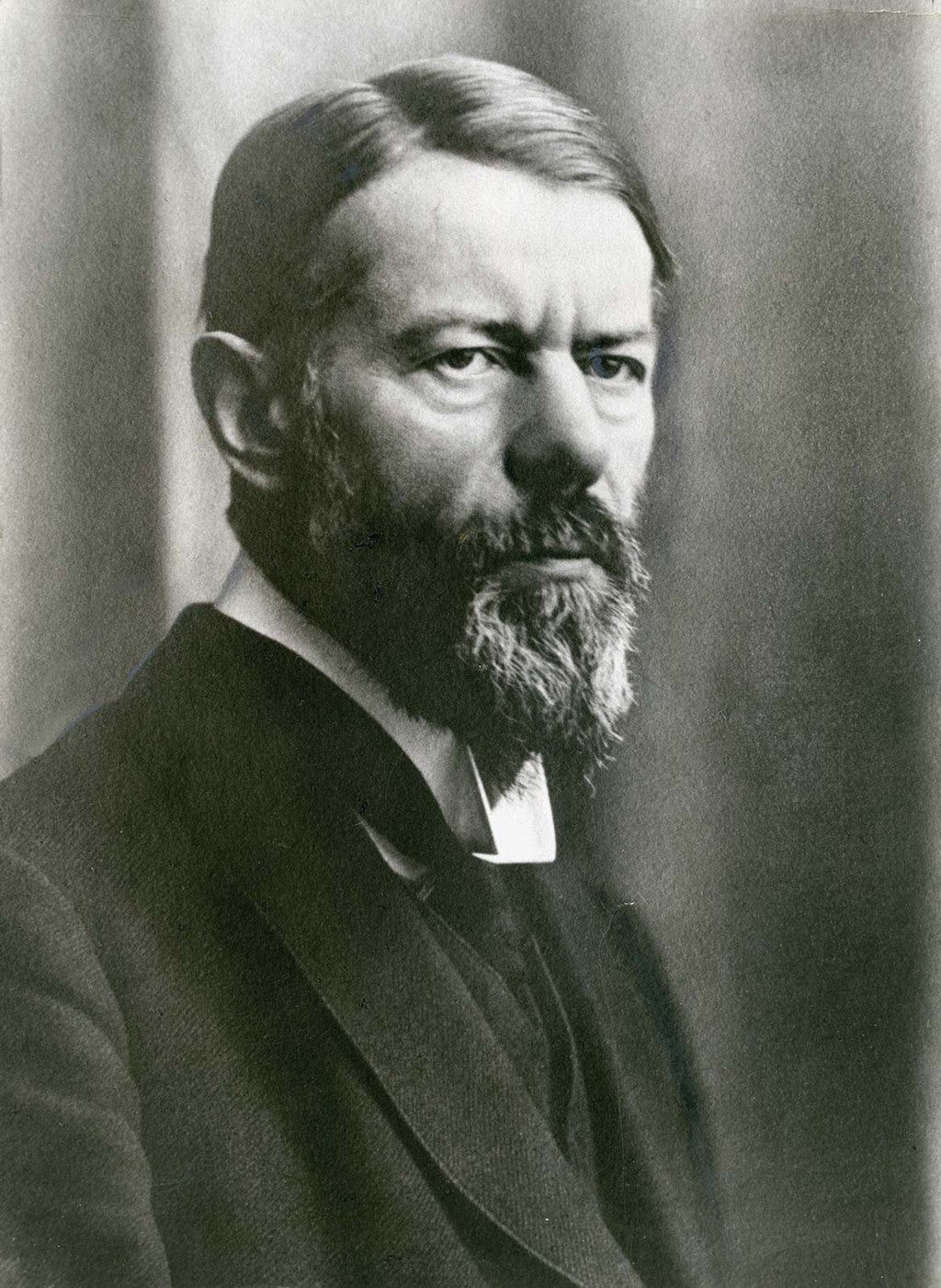

The word “holograph” means a manuscript handwritten by its author, as in the image of one of James’ letters, above. But I want to drag the word closer to its cousin “hologram,” a three-dimensional image composed of light. Their etymologies are nearly identical: holo, Greek for “whole",” attached in the one case to graphos, “writing” and in the other to gramma, “message,” or “that which is drawn or marked.” The holo in hologram alludes to the three-dimensionality of the drawing or marking; in holograph it refers to completeness, to the fact that the document in questions was produced by a single hand.

The irony is that the late James didn’t write by hand at all; afflicted by rheumatism that made it painful to hold a pen, in 1897 he began dictating his work each morning to a secretary who would type everything James said; James would then correct the typescripts that afternoon. As he explained to his last amanuensis, Theodora Bosanquet, “It all seems to be so much more effectively and unceasingly pulled out of me in speech than in writing.” That James’ sentences should become so much longer and more elastic and difficult to parse when he had to speak them out loud than when he wrote them himself is a nine-days wonder; somehow he spoke himself into a degree of writerliness he couldn’t achieve with his own hand and pen. But I’m more concerned with the effect of James’ holographic sentences on the reader.

When I call the fiction of the late James “holographic,” I refer metaphorically tantalizing qualities of the hologram, as suggested in these descriptions of the process of holography from Georgia State University:

Holography is "lensless photography" in which an image is captured not as an image focused on film, but as an interference pattern at the film….This recorded interference pattern actually contains much more information that a focused image, and enables the viewer to view a true three-dimensional image which exhibits parallax. That is, the image will change its appearance if you look at it from a different angle, just as if you were looking at a real 3D object.

…

Every part of a hologram contains the image of the whole object. You can cut off the corner of a hologram and see the entire image through it. For every viewing angle you see the image in a different perspective, as you would a real object. Each piece of a hologram contains a particular perspective of the image, but it includes the entire object.

Allow me the fancy of adapting this language as follows:

The fiction of late James is "lensless fiction" in which an image is captured not in an ordinary sentence, but as an interference pattern at the sentence level….This recorded interference pattern actually contains much more information that a focused sentence, and enables the reader to explore a true three-dimensional image of a narrative which exhibits parallax. That is, the narrative will change its appearance if you look at it from a different angle—that is, reread it—just as if you were remembering a real experience.

…

Every part of a holographic sentence contains the image of the whole narrative. You can cut off the corner of the story and see the entire narrative through it. For every viewing angle you see the story in a different perspective, as you would a real experience. Each sentence contains a particular perspective on the story, but it includes the entire narrative.

Yes, it’s only a metaphor, and it may not bear scientific scrutiny, but I find it useful for understanding why it is certain writers can only be reread and never read. The Beast in the Jungle is a good deal simpler than, say, The Golden Bowl, if only because it’s comparatively short and features only two named characters. But each of its self-canceling sentences evokes the indeterminacy we might feel trying to parse the thoughts of a person we’ve just met at a party; only upon rereading can we stand back, the way you stand back from a pointillist painting, and get the full sense of John Marcher’s obliviousness and May Bartram’s tragic dignity.

I think Emerson operates along similar lines in his essays; his sentences are not as long and wandering as James’, but they both have that crucial quality of self-canceling, of crumbling beneath the reader’s feet, of enabling readerly parallax. “Life,” writes Emerson, “is a train of moods like a string of beads, and, as we pass through them, they prove to be many-colored lenses which paint the world their own hue, and each shows only what lies in its focus.” Emerson strings his moods sentence by sentence, gleefully contradicting himself, trapping the reader into either reducing an essay to its bromides or—the desired end—thinking for themselves. James, perhaps oversubtly, strings his characters’ moods clause by refracting clause, in pursuit of the representation of our own uncertain probings, akin to what his brother the psychologist William James called “a feeling of and, a feeling of if, a feeling of but, and a feeling of by, quite as readily as we say a feeling of blue or a feeling of cold.”