Oh, hello there. You’re probably wondering why you haven’t heard from your gentle correspondent for awhile. Why haven’t I been writing to you about what I’ve been reading—since that seems to be what this newsletter is mostly about? Well, I’ve been writing other things. In addition to tinkering with a television pilot script or two, I’ve been working feverishly on a revision of my first science-fiction novel, the first version of which I completed in 2016 and sent out into the world with hopes of success as yet unmet. After letting it lie fallow for a good while, I got some fresh eyes on it that helped me see how I might revise it, and that’s been my major writerly occupation for the past six weeks. I’ve shaved more than thirty thousand words off the thing and it’s now a lean, mean, narrative machine. If anything comes of it then you, my faithful reader, shall be among the first to know.

There are only three books left for me to discuss in the Aubrey-Maturin series—two and a half, really, since 21 is incomplete. I find myself strangely reluctant to finish, unwilling to say goodbye to these dearest of fictional friends. I have been distracting myself with other reading matter instead. I’m still on a Trollope kick—as soon as I polish off one novel I start on another. (He wrote forty-seven novels so I’m going to be here for a while.) Having gone through the Barsetshire Chronicles I’m now onto the Palliser novels, having plowed through the wonderfully titled Can You Forgive Her? and its sequel, Phineas Finn. Whereas the Barsetshire novels preoccupy themselves with the doings of provincial clergymen, the Palliser novels are about the British Parliament and the men and women drawn like moths to the flames of power. They’re named for one of the principal characters, a fellow with the preposterous name of Plantagenet Palliser, heir to the immobile Duke of Omnium (who, yes, has a castle called Gatherum). The intersection of love, money, and politics is Trollope’s beat, and in the Palliser novels he trades in the pastoral atmosphere of the Barsetshire books for larger stakes, with the Second Reform Act at the center of the action of Phineas Finn, in which the titular principled MP finds himself repeatedly voting for the dissolution of the corrupt boroughs he represents, one after the next. But the doings of the British state, as with the British church, are I think less interesting to Trollope than the machinations of ambition. Trollope and his readers are a little like Lear and Cordelia in the old king’s Act V fantasy:

We two alone will sing like birds i' the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I'll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we'll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we'll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who's in, who's out;

And take upon's the mystery of things,

As if we were God's spies.

Lear and Cordelia die, of course. Trollope died a long time ago, but it is to be hoped that his readers must not immediately follow Cordelia’s example. So far I’m finding Trollope’s women far more interesting than the men—he’s refined in these novels a particular type of woman, who while far from being a suffragist is political to her bones and seeks to have access to and influence upon the power wielded by the men. Can You Forgive Her? is more of a romance than anything, but its subtext is the birth of a powerful political hostess in the form of the marvelous Lady Glencora, wife to Planty Palliser, whose dissatisfaction with her marriage is cured by the birth of a son and a corresponding birth of her own powers of influence over her husband. Phineas Finn gets down much deeper into the political weeds. I found its hero a feckless bore, but Lady Laura Kennedy, née Standish, is one of the great tragic characters of 19th-century English literature—a woman who married wisely but not well, and missed her chance at a husband with whom she could have truly partnered.

In between Trollope novels I’ve been picking away at Cormac McCarthy’s duology, The Passenger and Stella Maris. I started, as most people do, with The Passenger—what appears at least at first to be, like many of McCarthy’s other novels, a heightened genre exercise in the spirit of No Country for Old Men: an underwater plane, a mysterious missing passenger, men in black asking elliptical questions, etc. But the novel has much bigger questions on its mind, as suggested by the multiple identities of its hero, Bobby Western—a former racecar driver, the son of a Manhattan Project physicist, and the brother of a young mathematics prodigy named Alicia whose tragic story is at the center of the slender and enigmatic companion novel. As delicious as The Passenger is, I decided to put it aside and read Stella Maris first—it’s a spare book, consisting almost entirely of dialogue between the suicidal Alicia—who is in incestuous love with her brother, whom she believes to be brain-dead after crashing his Formula 2 car—and her well-meaning but hopelessly intellectually outmatched psychotherapist. The scope and bleakness and understated humor of the writing reminds me a little of David Lynch, and specifically of Twin Peaks: The Return, a show that I haven’t actually yet watched but which I’ve read a lot about and which seems to want to draw a similarly existential, elliptical connection between the creation of the atom bomb and the evil that men do.

Before those books I finally finished McCarthy’s campy revision of Faulkner, Suttree, a quasi-autobiographical Southern gothic about a man who walks away from respectability to live on the margins of society in a houseboat on the Tennessee River in Knoxville. The prose is frankly unbelievable, in almost every sense of the word. Here’s a passage selected more or less at random in which a curiously innocent reprobate named Harrogate, who at one point is shot and arrested for carnal knowledge of a melon, finds himself investigating the sewers of Knoxville:

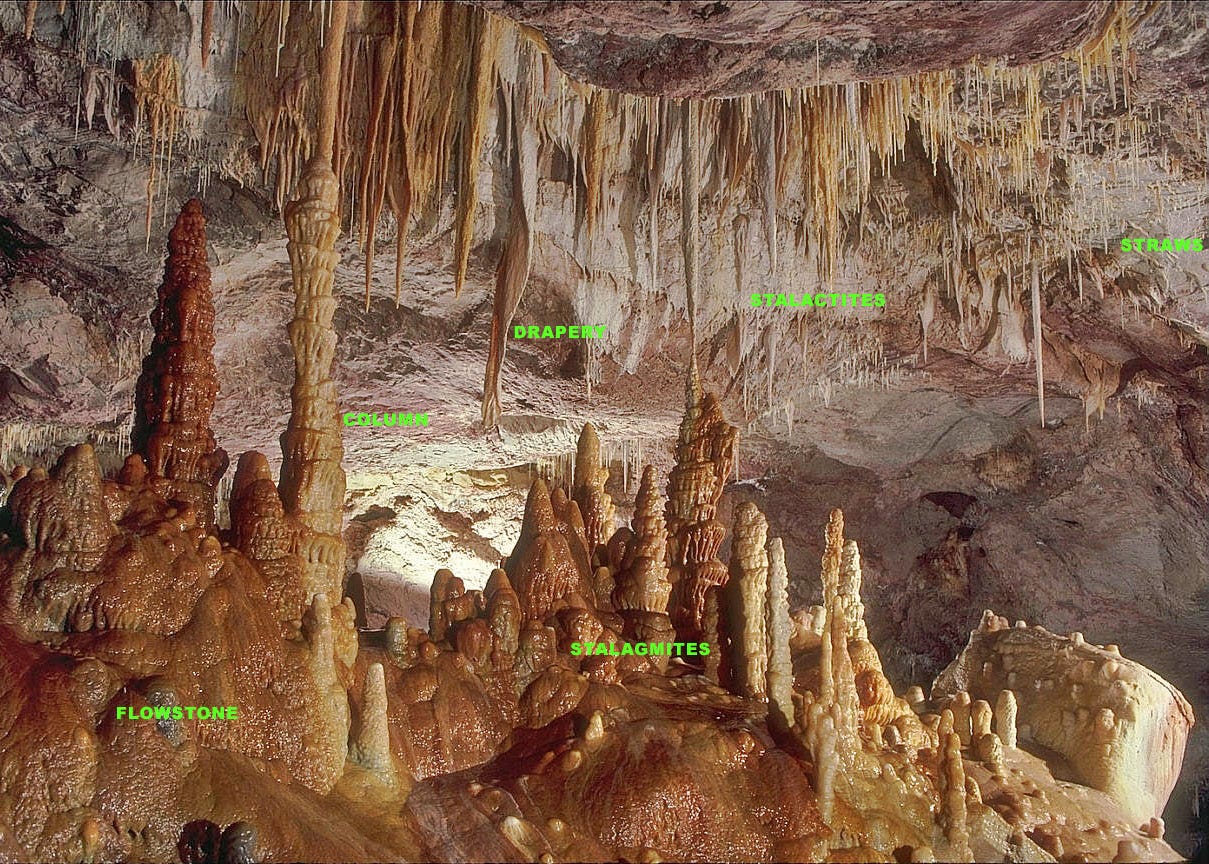

The matches that he struck periodically to test the air burned with an acetylene blue and he’d watch the flame draw down the matchstem and wink out and the darkness would hood him almost audibly. Sitting there with his thumb on the button of the flashlight and listening until the terror rose up in his throat and then pushing the button and creating again the filthy basilica in which he sat, the batclotted arches, the high amorphous convolutions of limestone from which scum dripped. Gray sewage percolating down through faults and bedding planes. Dark leachings from the city’s undersides and speleothems accresced out of some grim slime quietly oozing in the dark.

I have a pretty good vocabulary, but it wouldn’t be a Cormac McCarthy novel if there weren’t at least one word new to me per page; this time it’s speleothems. For my money, though, the exciting word in this paragraph is the verb form of hood, which captures so wonderfully and animistically the interaction of the environment with Harrogate’s mind. I’ve maintained a certain distance, a certain skepticism, regarding McCarthy since he became famous for his Border Trilogy back in the 90s; I was in no mood for his romanticism then, or really for any of the as it seemed to me overhyped white male writers of the period (I ignored David Foster Wallace and Jonathan Franzen with equal fervor). Now I’m all in, at least where McCarthy is concerned. I find myself moved by his commitment to precision, particularly in rendering images of the physical world, as figured by the man’s strategic deployment of his truly prodigious lexicon. The man is, as they say nowadays, a vibe. Next I’ll be tackling Blood Meridian—one of those novels I seem to perpetually reread to about the halfway point before setting it aside.

Speaking of halfway points, I am also halfway through my quasi-namesake Joshua Cohen’s upsettingly funny comic novel The Netanyahus. It’s difficult, to paraphrase William Carlos Williams, to get the news from novels, yet Cohen’s book, in which a nebbishy Jewish academic circa 1959 must be the deciding voice in hiring or not hiring Benzion Netanyahu, the Prime Minister’s father, onto the faculty of his obscure upstate college. I recently read a review of Benjamin Netanyahu’s autobiography in the TLS that did more to explain recent Israeli politics to me and Netanyahu’s own political survival, and by extension the political survival of other tribal populists, than a million thinkpieces have done. The reviewer, Ari Shavit, discovers a depth of cynicism in Netanyahu that is breathtaking for the sincere fear that stands behind it: he is willing to break any norm, democratic or otherwise, in defense of the Jewish people from every enemy, and is completely unable or unwilling to recognize the moral wreckage of that stance. I think Cohen’s novel follows a similar thesis, but unlike Shavit (or Bibi, for that matter), he’s screamingly, devastatingly funny. Each chapter is a can-you-top-this set piece, from the smooth microaggressions of our narrator’s department chair to the outrageous snobbery of his parvenu in-laws to the backhanded letters of recommendation arriving from Israel clueing us in to the fact that Benzion, like his son, is a fanatic for whom anti-Semitism is the perfect and only necessary explanation of the engine of history. This is the sort of novel, like Blood Meridian (which is also brutally funny) that I need to take breaks from, but it’s teaching me a great deal.

All right, you’ve talked me into it—this week I’ll pick up Patrick O’Brian’s The Hundred Days and get back into the Aubrey-Maturin swing of things. Back soon with a full report.