The horrors of the past eight nine days, apt to be dwarfed by the horrors to come, have left me wordless. I grieve for my fellow Jews; I grieve for the innocent Palestinians; I hope desperately that the Israeli government, in spite of its venality and incompetence, will pull back from the brink of repeating the self-destructive catastrophe wrought by the United States in response to 9/11. Others have written more eloquently about this moral and humanitarian disaster than I ever could. I will only say that I found myself in need of refuge today, and found it at a matinee showing at the Music Box Theater of Jonathan Demme’s 1984 concert film about the Talking Heads, Stop Making Sense.

The movie, like the music, is astonishingly fresh and compelling, not least for the incredibly physicality demonstrated by the performers. First among equals is of course David Byrne, who with his skinny limbs and quasi-autistic affect seems like the very symbol of what it’s like to be disconnected from your body, a floating, well, head. Yet the man is an incredible dancer, sweating like a warthog, at all times thrillingly present and alive, even as his herky-jerky movements remind us that the human body is, among other things, a machine. Mostly I forgot I was watching an artifact from the Eighties until the very end, when the whitewashed funk of “Crosseyed and Painless” kicks in and we see some shots of the big-haired crowd. I found myself deeply moved by the joy on display, a joy that arose out of the energy of the band’s insight, late in Reagan’s first term, into how fucked things were, and how much worse, in many ways, they were going to get.

It’s also quite moving to see these white suburban art school kids being joined onstage, one by one, by an incredible array of Black musicians, a rock integration sorely lacking at that time (the audience we glimpse is also unusually diverse, then or alas now). Byrne is the charismatic live-dead wire; bassist Tina Weymouth is an uncanny presence, a kind of bubblegum vampire; drummer Chris Frantz is charmingly goofy; Jerry Harrison an anonymous white guy with big hair. They and their music are elevated by the electric presence of backup singers Lynn Mabry and Ednah Holt (singers, but also incredible dancers), aloof keyboardist Bernie Worrell, grinning percussionist Steve Scales (drummers seem to have the most fun), and a simply smoking guitarist, Alex Weir. Jonathan Lethem, whose 33 1/3 book about the band’s 1979 album Fear of Music I would love to read, has spoken of the band’s “sneaky relationship to black polyrhythms and dance music, but putting a kind of a gawky white face on top that,” which is exactly right, and made both audible and visible by the ecstatic spectacle of the film.

Underneath the ecstasy lurks the specter of dread. When the film came out I was thirteen years old, and there were a thousand idotic op-eds about whether 1984 was really, you know, 1984, and President Ronald Reagan “joked” on a live mike that he had outlawed Russia forever and “the bombing starts in five minutes.” The movie passed me by; I knew the Heads for their radio hits (“Psycho Killer,” “Burning Down the House:”) and a few of their videos on MTV, but didn’t buy any of their albums (the most-played records in my dismal vinyl collection were probably The Who’s Quadrophenia and Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick). I didn’t then feel the sense of recognition that I do now. Watching the film today, I am struck by the remarkable physical resemblance I see between young David Byrne and Cillian Murphy’s performance as J. Robert Oppenheimer; cadaverously beautiful men caught in the act of somatizing their terrible insight into the nature of reality.

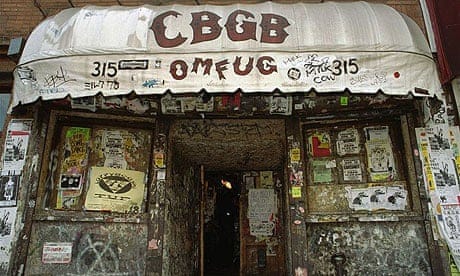

There’s something Lovecraftian about this incarnation of David Byrne, some collision between the merely human and the incomprehensible horrors of modernity, signified most memorably by the legendary “big suit.” It’s in his movements, it’s in his voice, it’s in his lyrics. In this moment of course it’s “Life During Wartime” that resonates most. We used to shout This ain’t no party! This ain’t no disco! at each other in the hallways of my junior high, and on one level it reads like a lesser Warren Zevon song in its depiction of the blank subjectivity of empire. But in the film, with Byrne collapsing on the stage wailing I changed my hairstyle so many times now / I don’t know what I look like, it’s the very image of apocalypse turned inward and outward again. The subject at the center of the song is both victim and perpetrator of the war, or more precisely of the wartime: a period of violent suspension in which the markers of everyday life and everyday identity are stripped away: This ain’t no Mudd Club, or CBGB / I ain’t got time for that now.

The showing I attended was sparsely attended, yet there were more people there than you might expect at 3:45 PM on a Monday, and there was a line of people in their twenties in the front row who reacted ecstatically to the film, hooting and waving their arms in the air and dancing in the aisles. When the projected words appear they shouted them deliriously: “ONIONS!” as a kind of Dada cry against the world of total commodification that the Talking Heads tried to reveal, the veil they tried to pierce to show the imperialism and racism festering under the sleek surface of Reagan’s America. These things are out in the open now, have been for generations, and yet the manufacturing of consent to genocide goes on. For 88 minutes, we sang along and danced and tried to forget—not the world outside, not the wartime that has conditioned my existence for most of my 53 years, but the illusion of innocence that floats toward us from every screen, threatening to utterly suffocate both individual response and the possibilities of solidarity, like a big suit in which our all-too-human bodies have gotten lost.