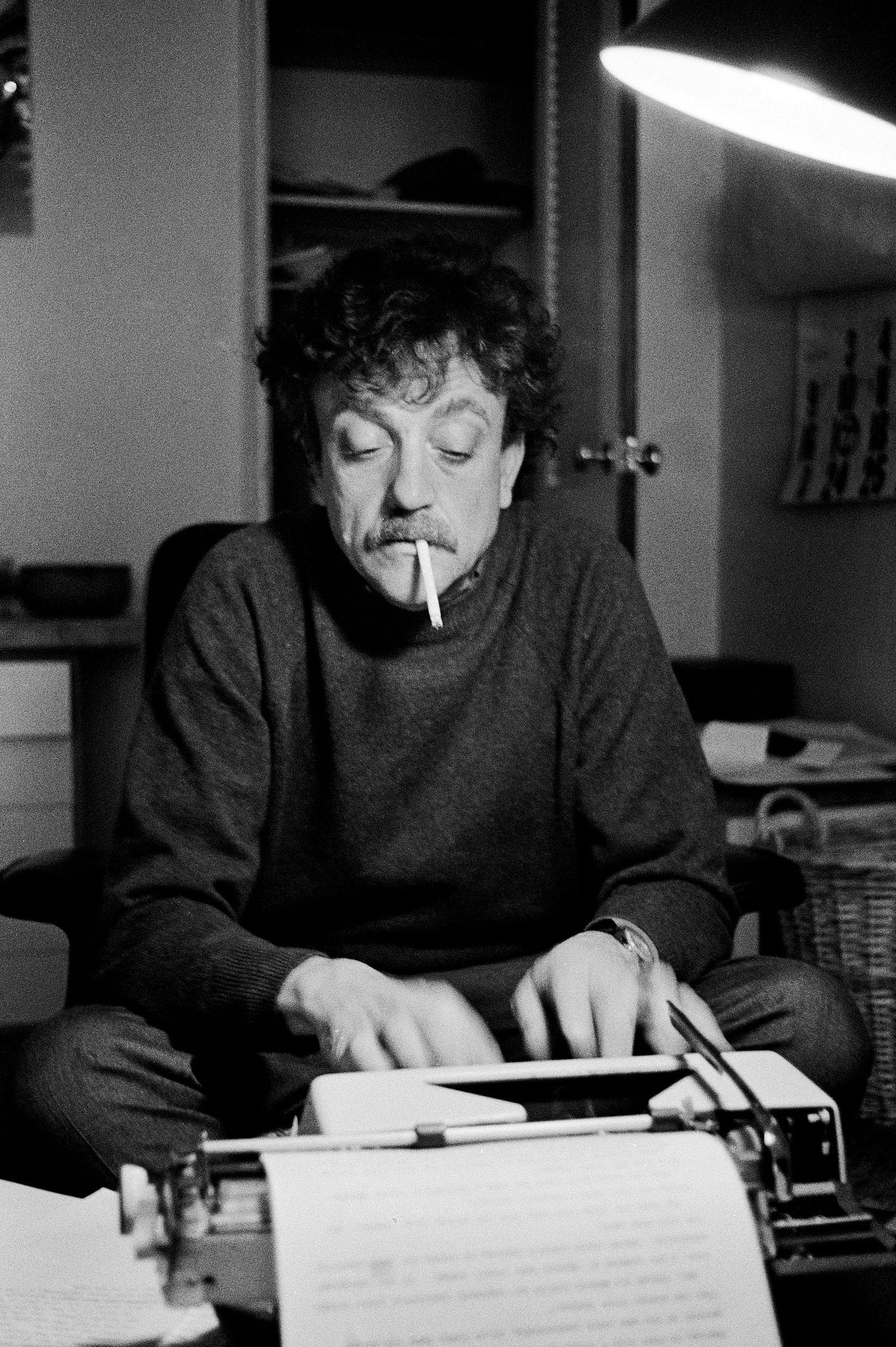

In Kurt Vonnegut’s science-fiction novel Slapstick, the protagonist, a would-be messiah elected President of the United States, institutes as his main and only policy the creation of new family ties between Americans by assigning clusters of them new middle names:

“As I said in my speech,” I told him, “your new middle name would consist of a noun, the name of a flower or fruit or nut or vegetable or legume, or a bird or a reptile or a fish, or a mollusk, or a gem or a mineral or a chemical element—connected by a hyphen to a number between one and twenty.” I asked him what his name was at the present time.

“Elmer Glenville Grasso,” he said.

“Well,” I said, “you might become Elmer Uranium-3 Grasso, say. Everybody with Uranium as a part of their middle name would be your cousin.”

“That brings me back to my first question,” he said, “What if I get some artificial relative I absolutely can't stand?”

“What is so novel about a person's having a relative he can't stand?” I asked him. “Wouldn't you say that sort of thing has been going on now for perhaps a million years, Mr. Grasso?”

This is a brilliant piece of idiocy, or maybe the other way around, that strikes at the heart of the American thing as it’s manifested in our literature and culture. As D.H. Lawrence notoriously remarked in Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.” Vonnegut’s fiction attacked each of those things: the hardness, the isolation, the stoicism, and the violence. No wonder I was drawn to him when I was younger, like so many other disaffected teenagers. He had put his finger on what seemed like a personal failing and turned it into a universal affliction, glorified by the word “American.”

I’m probably not lonelier than most, definitely not lonelier than some. I have a wife and family and friends; I have an enviable job as a professor; I get to talk about books all day, and write them, too. But since I was very small I’ve had an alien feeling or a feel for the alien, a feeling onto figures from movies and comic books: E.T., Superman, R2D2, and the list goes on. Sometimes I identify as the alien, robot, or replicant. Sometimes I’m the only human being in an alien world. It’s probably the human condition, if not specifically the American one. But I’ve always taken it personally.

I found a recent profile of the novelist Alexandra Kleeman in The New York Times all too resonant:

When she began writing, she started with poetry, since it didn’t require her to create fully formed characters. “Writing realist fiction seemed like such a high bar for me,” she said. “It involved understanding people so well that I could never hope to get there.”

So she takes comfort in genre: sci-fi, the post-apocalyptic, detective stories. Kleeman met her husband, the novelist Alex Gilvarry, at a Don DeLillo reading in 2013, and the two still swap Raymond Chandler and Patricia Highsmith books at their home in Staten Island.

I don’t know why it took me so long to connect the dots that are made here to practically overlap: I became a poet for the same reason I was (I am!) a genre fiction fan, because I too could never hope to get there. To realism, that is—the holy grail of the diminished enterprise we call literature.

It’s probably not a coincidence that Kleeman and Gilvarry meet at the points of a triangle: two of the great genre writers, Chandler and Highsmith, plus Don DeLillo, a metonym for the highest ambitions of twentieth-century postmodernism, who in the latter stages of his career seems to be turning into—wait for it—a science-fiction writer.

The problem of other minds, and others’ experiences, and otherness. Poems can thematize this with the slipperiness of their syntax; I read John Ashbery and am oddly comforted by the evidence of his own slapstick sense of isolation, as expressed by his tendency to follow the syntax of narrative even as each line undoes the premises of the line preceding it. Science fiction, of course, takes otherness as its subject: beginning with Frankenstein it confronts the violence that comes of projecting disavowed parts of oneself onto others. But realist fiction is something else again: it depends upon a discourse of mastery, of an understanding not just of “the human heart” but of the forces channeling its course that go by the names of class, gender, and race.

By "realist fiction” I mean a kind of social novel that reached its apogee in the 19th century and which never went entirely away, in spite of the challenges of modernism (which privileged subjectivity and the movements of consciousness) and postmodernism (which undoes the legibility prized by George Eliot, et al through its paranoid proliferation of overdetermined plotlines).

The latest “non-genre” challenge to realist fiction goes by the name of autofiction, though I think Brandon Taylor is more precise when he calls it “the contemporary novel of consciousness” and brilliantly compares the autofictional aesthetic of Rachel Cusk, et al, to “the Brutalism of the 1960s with its striking visual austerity and insistence upon materiality and shunning of anything that might impede the honest expression of that materiality.” The writers of this kind of novel have confessed impatience bordering on nausea with the devices of storytelling—a nausea that in Cusk’s case stemmed from the sense that nonfiction, too, was a dead-end. From a 2014 interview in The Guardian:

"Without wishing to sound melodramatic, it was creative death after Aftermath. That was the end. I was heading into total silence – an interesting place to find yourself when you are quite developed as an artist."

For almost three years, she could not write, she could not read. Novels seemed especially pointless. More and more – like Karl Ove Knausgård, whom she cites – she felt fiction was "fake and embarrassing. Once you have suffered sufficiently, the idea of making up John and Jane and having them do things together seems utterly ridiculous. Yet my mode of autobiography had come to an end. I could not do it without being misunderstood and making people angry." Using herself as the "template" was judged by some readers as a "wilful exposure of self, a washing of dirty laundry in public".

“Once you have suffered sufficiently”—I’m not entirely sure what she means here. The suffering of being pilloried for writing too frankly about one’s divorce? Ordinary human suffering? Or the peculiar suffering of the almost autistic personality revealed by Cusk’s self-description in her Paris Review interview, which I found by turns exquisitely painful and revelatory to read?

I have come through a similar crucible, possibly generational in nature, hinged on my sense of the deep unknowability of the things that a writer, a fiction writer especially, are supposed to know. This has required me to thematize my ignorance via various literary devices. In many of my poems I follow the Ashberyan (and I think Emersonian) path of dissolving my statements line-by-line, holding them in suspension, a pathetic solution in every sense. In my first novel the unknowable figure of my own mother is transmuted so many times that she dissolves in the transcendent pattern of the quest, like the figure in the carpet.

In my most recently published book, I stage a confrontation between two writers who represent on the one hand the deadly solipsism that became the spirit of National Socialism, and on the other the question of how people can live together without falling into mindless tribalism and scapegoating. That sounds intellectual and abstract, but if nothing else I hope the present essay hints at how deeply personal Hannah and the Master is.

My forthcoming book How Long Is Now is my most autofictional novel yet, returning obsessively to the unknowable ground of my parents before they were my parents. Beautiful Soul focused on my mother; my father takes center stage in the new book, but everything that happen takes place under the asterisk, the fig leaf of fiction, which will hopefully direct the reader’s mind along the path that maps my ignorance rather than taking the narrative for “a true story.”

And yet like Brandon Taylor I am nostalgic for the coherence of realist fiction, as beautifully expressed in this paragraph:

I start to long for scenes and description and a body and temporal relations to things. I start to long for the authorial presence to make some sense of the morass of narrative. I start to crave the old familiar structures of meaning-making. I start to wish I could pick up a book and not feel like I’m eating at one of those deconstructed restaurants where they charge you fifty dollars for some leaves on a plate with some paste.

For me following this path requires genre. I’ve been writing science fiction novels lately, though none of them have yet gotten into print, and they thematize on the level of plot my concerns with otherness, social knowability, and loneliness. Novel #1 imagines the moral and structural failings of a utopian community created by latter-day Transcendentalists; novel #2 recasts Emily Dickinson as an AI hologram upon whom the fate of civilization depends; novel #3, just completed, follows a cybernetic werewolf teen on a quest to discover her origins in postapocalyptic California. Writing these novels gifted me (and my eventual readers) with the pleasures of realism Taylor describes, yet they had to be speculative to circumvent the twinned dead-ends of autobiography and social incoherence.

I have more thoughts on coherence and its social and literary significance, as refracted through a summer in which I read a great deal of James Baldwin, whose Socratic methods of essay and fiction-writing struck me as deeply salubrious in a time of shallow affirmations and denunciations. But this post is already pretty long!

I am not sure yet what this blog, or newsletter, or whatever it is, will become. Maybe a return to blogging as in the high old days of the Aughts. Maybe a space for breathless confessions and shamefaced retractions. Maybe this will be the last entry. Who knows?

Now it’s time to melt some cheese and do some editing, and then maybe to write some more.