So I saw Ferrari and had a thoroughly good time—it’s a movie movie, operating perfectly at both ends of the cinematic spectrum: the intimacy of the close-up, and the wide-screen excitement of the chase (or race). As a filmmaker, Michael Mann plays a role in my aesthetic life rather similar to Patrick O’Brian’s: he’s a creator of hothouse worlds that center relationships between men, though both are capable of creating remarkable female characters. In Mann’s case much of the credit is due to his actresses—Penelope Cruz’s incendiary performance as Laura Ferrari is overwhelmingly great. Like O’Brian, Mann has an overriding interest in competence. For Jack Aubrey to call a man “no seaman” is to damn that man’s character, whatever other qualities he may possess; good seamanship covers a multitude of sins. Mann’s most iconic characters—James Caan’s eponymous Thief (1981), William Petersen as the first and best Will Graham in Manhunter (1986), Daniel Day-Lewis’s Hawkeye in The Last of the Mohicans (1992), and the cop-and-robber duo of Al Pacino and Robert De Niro in Heat—always impress us with their sheer skill and coolness under pressure, no matter what side of the law they’re on. The fifty-nine-year-old Enzo Ferrari, played improbably yet memorably by the forty-year-old Adam Driver, is yet another of Mann’s wildly competent and fundamentally lonely men, the master and commander of subordinates who demonstrate a nearly feudal level of loyalty to him (they even call him “Commendatore,” like the stony revenant from Mozart’s Don Giovani). If Jack Aubrey had never found a Stephen Maturin to offer him friendship and soften his sharp edges, he would have turned into a Michael Mann character: charismatic, driven, solitary. It’s all too easy to picture Jack alone on the quarterdeck taking in a superior enemy through his spyglass, muttering to himself: “The action is the juice.”

Heat is one of my favorite films, maybe even my favorite, full stop. When I stumbled upon Australian journalist Blake Howard’s podcast One Heat Minute, each episode of which is devoted to the critical dissection of exactly one minute from Mann’s 170-minute Los Angeles crime saga, it sparked my desire to do something similar, though less granular, for the Aubrey-Maturin novels. (Mike and Ian are closer to the spirit of that project with their own podcast.) Certainly the film is rich enough that Howard and his guests (who have included Manohla Dargis, Guillermo Del Toro, Bilge Ebri, Walter Chaw, and, for the closing credits, Mann himself) are never in any danger of running out of things to talk about as they dissect each sixty-second segment. Howard has developed similar podcasts devoted to other man-centric movies: Midnight Run Through (hey, what if Jack were a bounty hunter and Stephen his wily prey?), Miami Nice, and—drumroll please—Podcaster and Commander, which began last August and is still ongoing—excuse me while I go listen to the first episode right now.

(I’m back. Eh, it’s no One Heat Minute—there’s a purity to the one-minute-per-episode format that a mere documentary podcast with dubious sound quality can’t match, though it’s certainly enjoyable to find another point of entry into O’Brian’s story via Peter Weir’s now twenty-year-old film.)

But let’s get back to Mann, and Ferrari. In his review, Richard Brody focuses on Mann’s attention to detail, and on the attention to detail paid by his characters, intersecting with something I just read in David Salle’s review of the Alex Katz show at the Guggenheim in New York:

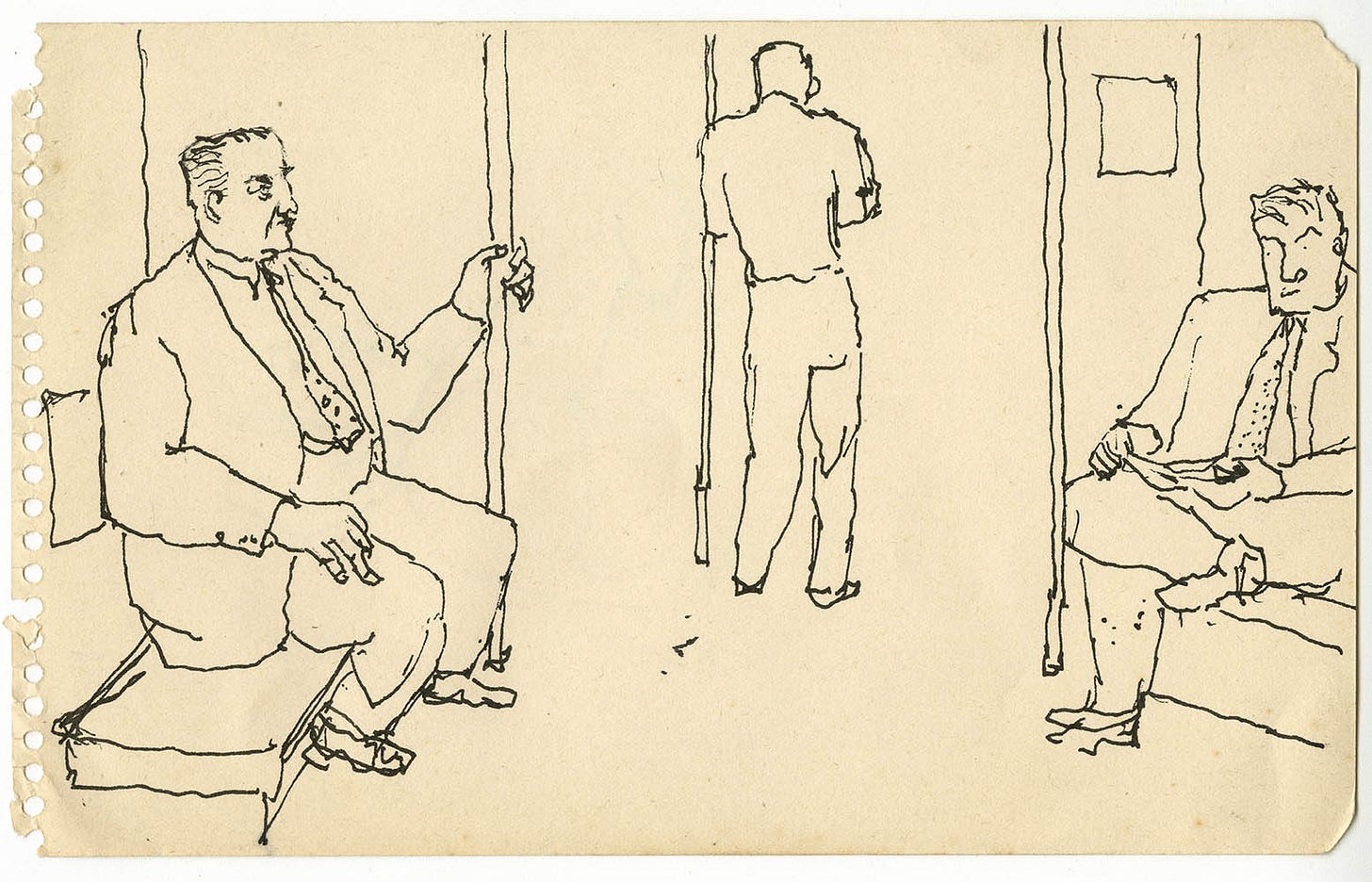

[Katz’s early drawings are] only quick sketches, but he was already absorbing a first principle: that specificity—of perception and also of the marks themselves—is everything; the generic is the enemy of art. To draw is to search for the essence of a scene, and a detail used well is a visual synecdoche, a part that can stand for the whole.

You can see what Salle is talking about in the sketch above—the exactitude of the postures of the three subway riders, particularly the way the man on the left has his right leg tucked slightly underneath the seat, and how the man with his back to us becomes the mysterious center of the scene, a visual synecdoche for the lonely crowd that anyone who’s ever ridden on a New York subway line will recognize. When I think back on the experience of watching Ferrari, similar key visual details come to mind: the close-up of a gearshift slotting or failing to slot into place, forerunner of a catastrophic accident; the face of a bank officer realizing he’s just said something he shouldn’t have to Penelope Cruz’s Laura Ferrari; the stopwatches pulled by every member of Ferrari’s team to check Maserati’s time while they’re all attending Mass; the terrifying and exhilarating racer’s point of view of a bending Italian road with who-knows-what deadly obstacles just out of sight; the farewell letter of a driver the night before a dangerous race, tucked into the frame of a hotel-room mirror.

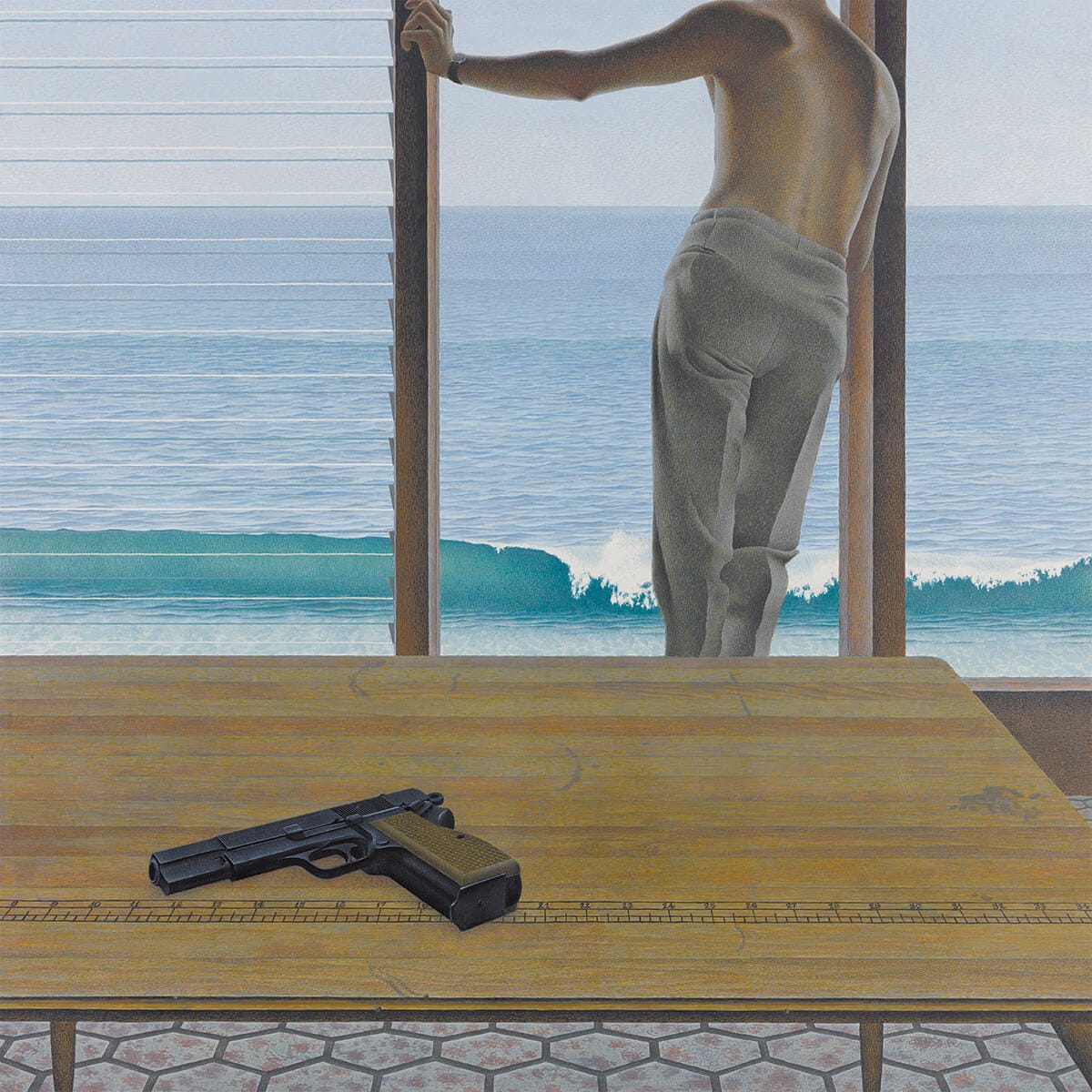

Such an image can be a synecdoche for an entire experience, an entire film—as in the pair of images below:

From Colville’s painting, which suggests nothing so much as a Southern California Hamlet intoning “To be or not to be” to the waves, Mann extrapolates the tautly caged and isolated figure of antihero Neil McCauley, gun literally at his back, imagining an escape to the sea. In a moment he’ll turn back to the meticulous planning of his next heist.

Mann’s films are crammed with attention to the technical details of whatever profession the main character obsessively follows, be that police work or safecracking or getting just a little more power out of an engine. This heightened level of attention persuades us but also aestheticizes the task—something made explicit in an exchange between Enzo and his illegitimate son Piero, who’s watching his father go over an engine diagram. “In all life, when a thing works better, usually it is more beautiful to the eye,” Enzo says. It is this beauty that obsesses him, and that trumps the dubious morality of Ferrari’s choices: to focus on racing over retail sales in a manner that endangers his company; to have a second family without his wife’s consent or knowledge; to endanger drivers and spectators in this beauty’s relentless pursuit.

It’s not a war movie, but the shadow of two wars falls over it; Enzo lost his brother (whom his tiny, fierce mother, played by Daniela Piperno, openly preferred) in World War I; he met his mistress and the eventual mother of Piero in the literal wreckage of his factory during World War II. War enables the pursuit of certain forms of perfection—this leads me back to the Aubrey-Maturin novels, which depict social and aesthetic triumphs for which the structural prerequisite is war. The intricate detail that makes these books so immersive, and which point by point build the portraits of Aubrey and Maturin (each of whom is obsessed by the details of his profession, whether that be naval warfare in Jack’s case or medicine, ornithology, and spycraft in Maturin’s) until they seem like people you could know. That obsessive quality seems to go cheek-by-jowl with an appetite for risk, for tolerating the losses that such a high level of commitment to things can bring.

In a remarkable pair of scenes, early on in the film, Enzo and Laura go—separately—to the grave of their son, Dino, who died of muscular dystrophy at the age of 24. Enzo sits in the tomb and talks to his son until he bursts into tears—a rare display of vulnerability witnessed by no living person. As he leaves, Laura arrives—a powerful image of their estrangement. Taking her seat in the tomb, looking at her son’s photo, she says nothing at all. The face of Penelope Cruz, as it flies through myriad expressions, without a word being spoken, for what felt like a full minute—this moment alone ought to earn her an Oscar. It’s a curious inversion of how they are in the rest of the film: Enzo, holding his body tightly, wastes few words, while Laura boils over with grief and rage and a lingering despised tenderness for the man she once loved, who in the film’s most significant gesture hands her the power to destroy him in the form of a check that, if cashed, will bankrupt his company.

“Our life is frittered away by detail,” writes Thoreau. Enzo Ferrari’s life is refracted through the mechanical details that seize his attention (like an engine design) and the human details from which he is so often distracted (like whether his son Piero will be permitted to take the name Ferrari). What he demands from himself and from the people who work for him is “a brutal determination to win. A cruel emptiness in their stomachs. Detached men.” He tells his lover Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley) that he realized early in his career as a race driver, after losing two friends on the track, that he had to either build a wall, or go do something else. But the cost of such compartmentalization is high, presented most brutally in a shocking scene toward the end of the film, when one of Enzo’s cars, running the Mille Miglia in the Italian countryside, loses control and scythes through a group of bystanders, killing ten people, half of them children.

“It is good that war is so terrible,” Robert E. Lee supposedly said, “or men should grow too fond of it.” Motorsports are not war, yet some men (and women too, no doubt) yearn for an activity so complete, so consuming, as to focus and shape their whole being through it, without the complications and confusions of lives lived in relation to others without hierarchy. Watching Ferrari, thinking about the “butcher’s bill” paid by innocents and combatants alike, I think of William James’ idea of “the moral equivalent of war”: “the strong life; it is life in extremis.” As James eloquently puts it, “Fidelity, cohesiveness, tenacity, heroism, conscience, education, inventiveness, economy, wealth, physical health and vigor—there isn't a moral or intellectual point of superiority that doesn't tell, when God holds his assizes and hurls the peoples upon one another.” Who can deny that these are virtues, qualities only hinted at by archaic words like honor and valor? And who can deny that these virtues, when aroused in war, are accessory to titanic suffering and waste?

James calls for the replacement of military honor with what he calls “civic honor”: competitive pride in a collective identity harnessed in the form of service to one’s community. Disconcertingly, in James’ early twentieth-century formulation, this would take the form of “an army enlisted against nature”—universal conscription in the cause of taming “this only partly hospitable globe.” Mann’s protagonists pursue something like this kind of of honor, not least by making war on their own nature, by building walls, by outsourcing emotional labor to the women in their lives. To live more intensely a part of them must die to themselves, and, since cinema is a visual form, we watch them die and live in the same moment. The last scene of Ferrari shows Enzo and Piero at the cemetery where Dino is buried: Piero, who could never replace Dino, will nonetheless in due time replace his father (a title card at the end informs us that “Piero Ferrari is the vice-chairman of Ferrari S.p.a.”). It is a little like the end of Heat, in which the cop kills the master criminal who was his second self.

Enzo is a figure of authority. We might recall what Stephen Maturin has to say on the subject in Master and Commander:

It is odd – will I say heart-breaking? – how cheerfulness goes: gaiety of mind, natural free-springing joy. Authority is its great enemy – the assumption of authority. I know few men over fifty that seem to me entirely human: virtually none who has long exercised authority. The senior post-captains here; Admiral Warne. Shrivelled men (shrivelled in essence: not, alas, in belly). Pomp, an unwholesome diet, a cause of choler, a pleasure paid too late and at too high a price, like lying with a peppered paramour. Yet Ld Nelson, by Jack Aubrey’s account, is as direct and unaffected and amiable a man as could be wished. So, indeed, in most ways is JA himself; though a certain careless arrogancy of power appears at times. His cheerfulness, at all events, is with him still. How long will it last? What woman, political cause, disappointment, wound, disease, untoward child, defeat, what strange surprising accident will take it all away?

We glimpse “natural free-springing joy” once and once only on Adam Driver’s face: as the very young Enzo winning a road race. The ravaged Enzo of 1957 calls the work he and his drivers do “our deadly passion, our terrible joy.” It is that living contradiction—something more dialectical and alive in the nerves than mere compartmentalization—that may be Mann’s most authentic subject, and O’Brian’s too.