As the summer winds down I finish or try to finish various tasks—revising, for the nth time, a science-fiction novel and sending it off to my agent; working on syllabi; editing an interview I did of the legendary poet Michael Anania—I keep an eye on what really holds my attention. I don’t know about you, but there is always in my life a conscious current of activity and a less conscious counter-current. This summer, the counter-current has been reading The Journals of John Cheever, along with rereading classic stories like “The Enormous Radio,” “The Country Husband,” and" “The Five-Forty-Eight.” It started with Olivia Laing’s The Trip to Echo Springs: Why Writers Drink, which I inhaled a couple months ago. Laing explores the destructive role played by alcohol in the lives of six iconic twentieth-century writers: Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Berryman, John Cheever, and Raymond Carver. Each of these writers were important to me in my younger and more vulnerable years, with the noted exception of Cheever, whose lapidary stories seemed too deeply embedded in the boring suburbs I’d so recently fled. I’m not interested in alcoholism per se; it’s the impulse of alcoholic writers to dramatize their psychic wounds with varying degrees of metaphorical flamboyance that has always caught my eye. But Laing’s book swung my middle-aged attention to Cheever’s pathos, and his lyricism.

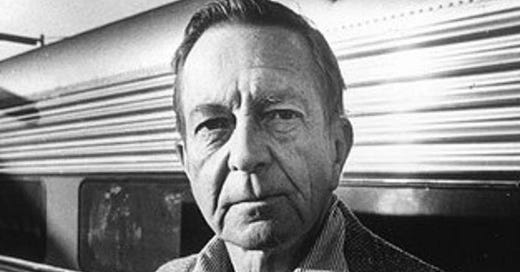

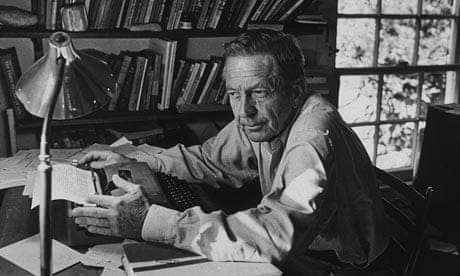

Who thinks about Cheever now? He belongs to the mid-century pantheon of pale males: Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, John Updike. His beat was middle or upper-middle class loneliness in the Westchester set, medicated by adultery and alcohol. He was, or appeared to be, the quintessential New Yorker writer, with all the strengths and weaknesses appertaining thereto. Dive into the prose, however, and you will catch much stranger fish than you might expect. For one thing the man had an astonishing ability to capture the pleasures and torments of sensuality in his sentences; he is the sort of writer capable of a degree of attention to the physical world that becomes transcendent, not by any over appeal to higher values but simply by the quality and intensity of that attention. I related especially to this remark from the journals: “I read George Eliot and find myself to be so physical a person, so tactile, so crude, that when anything is touched—when Deronda at last puts his hand around an oar—I am thrilled.” And here is an example of Cheever’s own tactile prose, chosen at random from a 1959 journal entry:

It is a rainy Sunday and the smell of pew cushions is dense. One can hardly hear the priest, the noise of rainspouts is so loud. I seem to be back at the farm, a happy child, sitting on burlap cushions and hearing rainspouts. For a second the recollection is so vivid, so full, it is like the rush of memory brought on by a mouthful of hot pudding.

The Proust is in the pudding! Cheever is a great noticer, and a great crafter of images—I wish I were more gifted in this realm, which seems to me the essence of art. Though I selected the passage at random, it seems not insignificant to see Cheever’s sensuality manifesting in church (he was a high-church Episcopalian, and I wonder if his religious sensibilities were of help to him when he finally broke up with the bottle in the last half-decade of his life). The journals are suffused with self-pity polished to a high sheen, but they frequently evoke the beauty of nature to a sacramental degree that locates Cheever in the direct line of Transcendentalism. Drop Thoreau into the suburbs, give him a libido and a glass of gin, and you’d have something like John Cheever on a good day.

As recently as the 1990s, nothing was taken more seriously, literarily speaking, than the inner lives of white men restlessly confined by middle-class mores. John Updike was an inescapable presence as both novelist and critic; every new Philip Roth novel was an event; Saul Bellow’s last novel, Ravelstein, echoed the cultural event that was Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind—in hindsight one of the last protesting gasps of serious culture in this country. Today these writers are unfashionable; Updike in particular seems to have vanished down the memory hole, fifteen years after his death, and is most frequently remembered for his cringy sex scenes. Nowadays there’s a fair bit of handwringing going on about the fate of the male novelist, as there is about the fate of male readers. To reread Cheever, however, is to be reminded that the stereotypical image of these writers and their characters as overprivileged sexist horndogs is to miss the yearning intelligence that they turn on themselves and their failings. That’s especially true of Cheever’s more surreal stories, such as “The Swimmer,” whose protagonist tries to transcend his own limitations through the perverse feat of swimming home through the suburban swimming pools of the postwar patriarchy; time bends strangely as the story progresses, and when he finally arrives at his own door he’s become a lonely and bewildered old man. There’s a truthfulness, and richness of metaphor, in Cheever’s writing that matters at least as much as his identity as a middle-class white man. Not to mention more than a hint of a connection between his fragmented experience of identity (“I am queer, and happy to say so,” he writes in a late journal entry) and the synthesizing grasp of his metaphors.

“The Country Husband” is perhaps the archetypal Cheever story, featuring a limited man, Francis Weed, who runs up against “the strenuousness of containing his physicalness within the patterns he had chosen.” The opening reminds me strongly of one my favorite films, Fearless (1993): Weed is on an airplane from Minneapolis to New York that has a mechanical emergency and is forced to make an emergency landing in a field in Pennsylvania. He gets home to Shady Hill before any news reports, and finds himself utterly unable to communicate his near-death experience to his family. There is an unspoken parallel, I think, between this experience and the PTSD of World War II veterans, of which Cheever was one. This is made manifest later in the story when Weed recognizes a neighbor’s maid as a Frenchwoman he encountered when he was a soldier, being punished for collaborating with the Germans by being stripped naked and having her hair cut off. She is, to borrow from the title of another Cheever story, a chimera, a mysterious emblem of the sexual unruliness that possesses Weed, which after a desperate struggle he re-sublimates with the help of a psychiatrist named Dr. Herzog. The ending of the story is justly famous for its depiction of the pagan forces roiling just under the serene surface of this prosperous suburb: “Then it is dark: it is a night where kings in golden suits ride elephants over the mountains.”

My father read Cheever—it’s his hardcover copy of The Stories of John Cheever that now sits on my shelf—and Roth, and Updike with a particular avidity, as though looking for himself in their pages. Dad wasn’t an alcoholic, but he was a raging sensualist with an eye for women and the woe that was in marriage (in his Paris Review interview, Cheever is asked for an example of “a preposterous lie that tells a great deal about life” and responds “The vows of holy matrimony). He was not a veteran, nor bisexual the way Cheever was. Nor could he be described, as Cheever’s shrink devastatingly does, as "a neurotic man, narcissistic, egocentric, friendless, and so deeply involved in [his] own defensive illusions that [he has] invented a manic-depressive wife." Still I feel like I’m on Dad’s trail somehow as I read Cheever’s stories and even more so his journals, so frank about his desires and frustrations and the blame he puts on his long-suffering wife, and his helpless love for his children.

Nowadays what seems most remarkable is to have had a father who read novels at all. Men, they say, don’t read, and when they do read they don’t read fiction. My father read plenty of stereotypical “dad” books—presidential biographies, popular histories, World War II books, etc.—but he was of a time and place when you had to read novels if you wanted to partake in the culture, and so novels made regular appearances on his bedside table. I don’t know if my mother’s reading habits had any affect on him, or if they ever read the same books. She mostly read poetry (Plath, Sexton, Rich) and trashy genre fiction (Agatha Christie, horror novels, medical thrillers), alongside second-wave feminist classics: The Second Sex, The Feminine Mystique, et al. Though I think of her as being more intellectual, her taste in prose was arguably more middlebrow than his; she read John Steinbeck and Michael Crichton, he read Richard Ford and Don De Lillo. I think he was looking for himself when he read novels; I think she was looking to escape. I wish I could talk to them about it now.