Once in a lifetime

What 2025 may bring

January always takes me by surprise. It shouldn’t—I know very well what month comes after December—yet the transition is always bumpy. The spring semester, which seemed so remote just a few days ago, is suddenly at hand. The days, or at least solid consecutive hours, in which I can write are suddenly numbered, scarce. And a reflective mood comes upon me, in which I can acknowledge beautiful wife, house, and child as mine while still asking perplexedly, How did I get here? Ruminations follow.

What is this thing, this dream, this blog? It is a blog, isn’t it—the spirit of blogging, that mild west of the early aughts Internet, has returned in bastard form. Having cut the cord on X/Twitter, and barely using or caring about Instagram, Substack has become my primary mode of engaging with the virtual world. I am reading a lot of Substacks now, probably too many, and marveling at the variety. In no particular order, and with the caveat that I will inevitably leave out a lot of interesting ‘stacks and writers, I’ve been reading:

Justin Smith-Ruiu’s The Hinternet gets pride of place because it was the first Substack I encountered that seemed truly strange, truly its own thing. It made this platform seem like it could be a home for genuine eccentricity, anchored in histories and geographies that Smith-Ruiu makes palpable in a very un-Internetty way.

Laurence Weschler’s always surprising Wondercabinet; he’s a true culture vulture with a bottomless reservoir of stories to tell about fascinating artists and thinkers, most of whom, like Lesley Hazleton, I’m hearing about for the first time.

Paul Franz’s ashes and sparks, which today features a fascinating meditation on D.H. Lawrence’s philosophy. (I have a soft spot for Lawrence as one of the few male modernists to take marriage seriously.)

Morgan Beatty’s The Futureness, which as serialized science fiction offers one model for how Concord may unfold.

Lincoln Michel’s invaluable Counter Craft, full of practical advice on fiction writing; I share his essays with my writing students frequently, especially the stuff about the pitfalls of writing fiction when TV rather than novels has supplied the bulk of your experience of narrative.

Mary Gaitskill’s Out of It—in some ways this platform is most interesting when a non-digital native such as Gaitskill gets hold of it. Plus she’s a simply fantastic writer, whose prose runs unpredictably cold and hot.

Sam Kriss’ Numb at the Lodge. If you know, you know.

Naomi Kanakia’s Woman of Letters. Opinionated, fearless, funny.

Sam Kahn’s Castalia. Clever boy.

BDM’s Notebook. BDM and Kahn are two examples—there are many more—of younger-than-me writers engaging with writing and publishing as it happens today in sharp ways that help me feel like I might actually understand how all this works one day. Also, I quite liked this.

I could certainly go on, but ten is a nice number.

I have decided to remove the paywall from all of my posts, at least for now. I didn’t start this thing to make money—the fact that I have made a few bucks, enough for an overpriced coffee or two, pleases me, but I’m much more interested in exploring the creative possibilities of a space that seems to have room for everything: reviews, stories, novels, the occasional poem, obsessive rereadings of Aubrey-Maturin, autobiography, what have you. Please help me celebrate the dropping of the paywall by letting other folks know about Dream of a Rarebit Fiend, won’t you? I don’t expect to ever have thousands of readers, but one thousand would be nice. A lover of melted cheese can dream.

This doesn’t mean, by the way, that I don’t appreciate financial support from those of you who have offered it or contemplate doing so! By all means keep buying me those overpriced cups of coffee. More caffeine —> more writing!

I have, as usual, a number of writing projects in hand. The most exciting is the serialization of my science-fiction novel Concord, which will begin with Chapter 1 this coming Sunday, January 5th. It’s the story of Saul Klein, a former corporate fixer turned resident of Concord, a floating city-state created by billionaires to escape the mainland’s collapse. Numbed by guilt and regret, Saul is awakened by a chance encounter that leads him to make the desperate resolution to escape his libertarian paradise for a more uncertain future.

This will be the first time I’ve self-published fiction, and I’m doing it for several reasons. The most obvious is that I hope to build a readership for it, so that I can eventually publish it in book form—I’m twentieth-century enough to still crave the solidity of paper books. But I’m also interested in what can happen when a work of fiction unfolds in time. Did readers’ letters influence Dickens when he was serializing Great Expectations or Bleak House? Did they make those books better? I am wary of audience capture; I don’t want to pander to what readers say they want. The best art always emerges from a singular point of view, whatever its flaws. But I’m interested in the possibilities of less monological forms of literature, and science fiction in particular seems like the right genre for exploring them. Inevitably, by being published alongside my usual occasional musings on whatever, the novel will take on a metafictional dimension that it wouldn’t otherwise have. We shall see!

Speaking of blogs and metafiction, or perhaps I should say metapoetics, back in the day one of my favorite poetry blogs was maintained by Jordan Davis, and many merry dialogues went on between us. He also used to host The Million Poems Show, a traveling talk show in which he would do his best Dick Cavett imitation while hosting poetry readings. Here from 2006 is Sasha Frere-Jones, of all people, singing what might have been the show’s theme song:

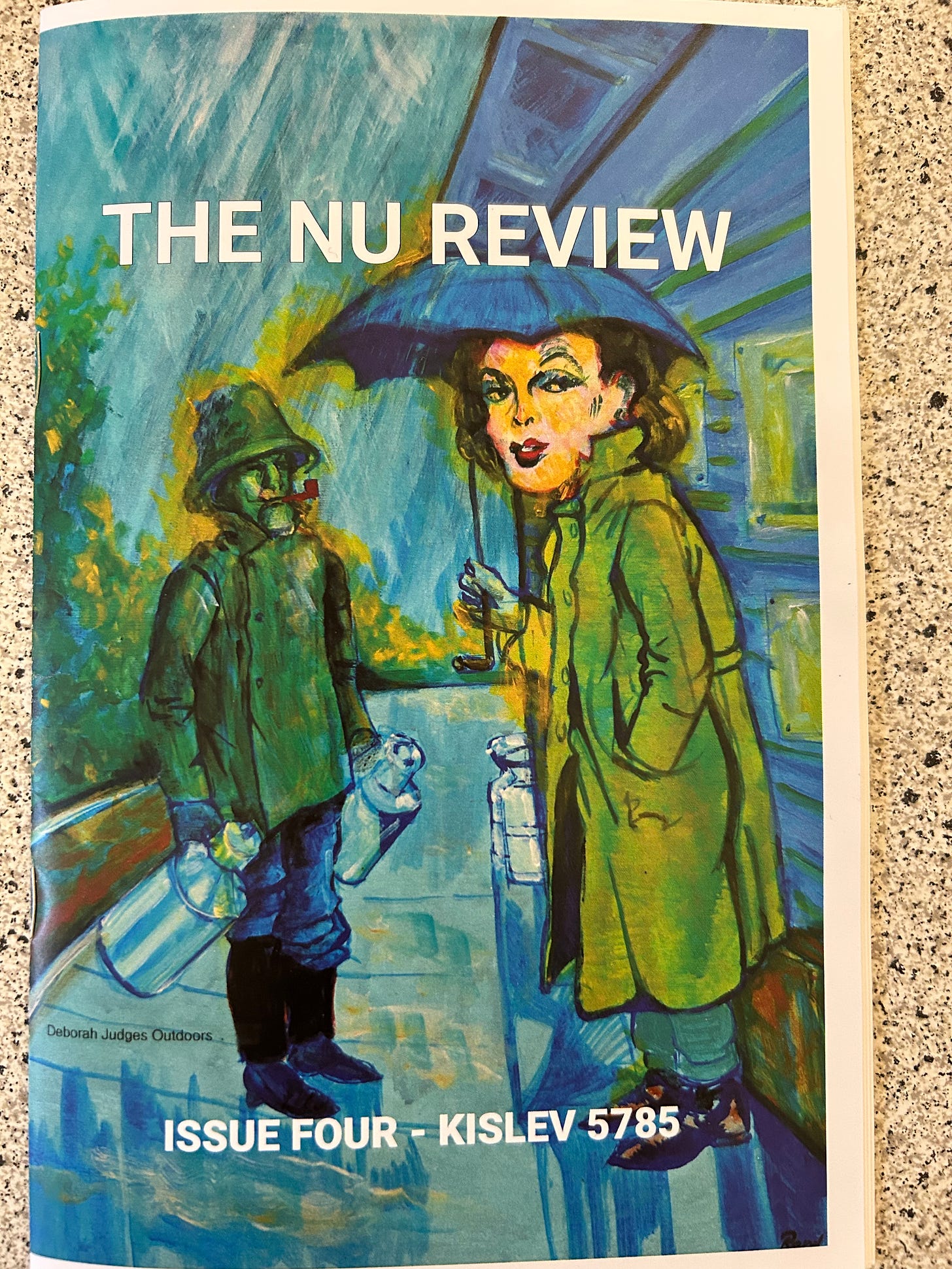

Anyway, these days Jordan is editing a (very) little magazine on Jewish-ish themes, The Nu Review, and he kindly included an excerpt from my novel-in-progress The Last Words of Jack Ruby in the latest issue. Here’s what that looks like:

So that’s fun! And a much-needed kick in the pants; the mansucript stagnated for much of the fall semester while I was spinning plates as interim department chair. But over the break I’ve been able to resume work on it, and I now feel confident in having a completed first draft this year.

You’ll notice the novel is called The Last Words of Jack Ruby but this excerpt is called “Barney Ross on Guadalcanal.” The novel actually has three, or maybe four, protagonists:

Jonathan K. Bergman, a (fictional) young FBI agent tasked by J. Edgar Hoover with getting the truth about Jack Ruby’s murder of Lee Harvey Oswald before Ruby dies;

Barney Ross, the legendary Jewish boxer, who happens to be a distant cousin of mine.

Jack Ruby, notorious nightclub owner and the assassin of JFK’s assassin, who grew up with Barney and was friends with him all his life.

The Golem of Prague, and the Rabbi who created him.

I’ll keep you posted on how all this progresses. For now, if you’d like a copy of The Nu Review (this issue also features fiction and poetry by Stuart Ross (the Canadian one), Sharon Dolin, Nada Gordon, Alex Dicklow, and others), backchannel me and I’ll see if Jordan has any copies left.

Bright, triumphant metaphors of love. I am listening to Nick Cave’s Wild God on vinyl, an album that makes me cry. Going to see him perform for the first time at the Salt Shed in Chicago next month. If you’ve never read his Red Hand Files, you should.

Another new-old project is the new Fortnightly Review. What is The Fortnightly Review? Well, it’s this, but it’s also this. I’ll have more to say about it shortly.

Another science-fiction novel of mine goes on submission in the spring. Fingers crossed. If that doesn’t work out, but serializing Concord does, expect to read it here, but probably not before next year.

(I’m a prolific motherfucker, aren’t I? Folks, I have no other hobbies. As good an answer to the how did I get here? question as I’ve got.)

Preliminary thoughts on AI: my initial, visceral response to the dawn of the LLM was fear and revulsion, and an instinct that its primary cultural impact will be negative. If it can be used to cure diseases and solve real-world technical problems, it might offer a net social benefit, but as far as art goes, I only foresee enshittification, unless and until people learn to treat AI itself as a medium like words or paint and not as substitute for craft. Still, as Ethan Mollick and others never tire of repeating, whatever AI you might be using now is the worst AI you will ever use. I will admit to making use of Claude and ChatGPT as a kind of sounding board; I would never use either to create actual text that I’d claim was my own, and not just because even the best of it is invariably bland and mealy-mouthed. But as a kind of diary that can talk back to you, reflecting your own interests and sometimes making unexpected connections, it has its uses. Some writers have, or used to have, editors with whom they could have productive conversations about their work; some writers have spouses or friends to play that role. For the many writers who don’t, I suspect AI will be most valuable as a kind of sub-editor, performing the Max Perkins-esque function of mirroring the work to help you see its flaws and potentials.

I am a little curious about the artistic potential of AI as a medium, by which I mean as something that an artist can learn to manipulate and stress-test and thus lead to the creation of works or experiences that would simply not be possible in painting, photography, filmmaking, etc. I am venturing tentatively into using AI image generation so as to give a visual tag to each of my Concord chapters. My method is to generate a phrase that will conjure a kitsch image, then ask the bot to deform or streak the image in some way. That seems actually appropriate for Concord, which is premised on a libertarian billionaire’s misunderstanding of New England Transcedentalism/Fourierism; I imagine the resulting aesthetic as Ayn Rand meets Currier and Ives. The image I came up with for the project as a whole is rather successful, I think:

Though it would be better if I could persuade DALL-E that the distant background should look like the sea!

The last 2025 project I can talk about is my new poetry collection. Well, it isn’t exactly new. Rather, I have the opportunity to publish a new-to-the-world collection on MadHat Press, the trusty publisher of two of my recent books. I am trying to decide between an old manuscript and a more recent manuscript; which do you think it should be?

The old manuscript, which was available for a time on my website, is called The Nature Theater of Oklahoma, after the artistic collective that absorbs the hero of Kafka’s unfinished novel Amerika, aka The Man Who Disappeared. I finished this book twenty-five years ago, but never succeeded in winning any contests with it (which is how most poets publish their books, or used to). But its concerns with Jewish identity and the use or misuse of the Holocaust in supporting that identity seem uncomfortably current; I now think of it as a kind of prequel to Hannah and the Master. It might be interesting, then, to publish it and put it in dialogue with that book, which has yet to get its due (unless one-star reviews on Amazon count).

The newer manuscript is called The Great Outdoors, the title of which emerged from my brief fascination with OOO, aka Object-Oriented Ontology, but it also stages a kind of intervention into my man Emerson, most specifically his great tragic essay “Experience,” the occasion for which was the death of his five-year-old son. All of my permanent fascinations are represented here—Transcendental utopianism, grief as ladder out of (or deeper into) solipsism, Kurosawa and Kubrick, sinister landscapes, etc.

I welcome your thoughts and notions on these matters.

It seems to me that serializing a novel has an obvious danger: each instalment you publish limits what you can do thereafter. For example, if somebody dies in Chapter 4 and later you decide you want to bring them back - what do you do then? I wonder how Dickens and other greats who published this way dealt with the problem. Probably the way long-form TV producers do today (however that is).

As a huge fan of both Emerson and Kafka, I think they both sound interesting. I teach "Experience" in my Transcendentalism class, and I teach Kafka (but not Amerika) in a different one. The last chapter of Amerika is fantastic, though I guess it's not at all clear he actually intended the "Open Air Theater" section as the end. It'll always feel like the end to me, though.

I think I like the first idea just a little better. It's timely, as you said, and think how satisfying it will feel to finally have the old manuscript out there.