Palpable Present Intimate

The speculative fictions of Henry James

Henry James is no one’s idea of a genre fiction writer—in spite of the fact that he frequently dabbled in tales of the supernatural, or stories open to a supernatural interpretation (The Turn of the Screw being only the most famous example). He was hard on historical fiction in particular, as shown in a famous letter he wrote in 1901 to Sarah Orne Jewett, in which he rebuked a novel she’d written set during the American Revolution as “condemned… to a fatal cheapness.” The lesson of the Master was that the goal of the novelist ought to be the representation of human consciousness, and he thought it impossible for a writer of one era to present “the real thing”—the consciousness of the past.

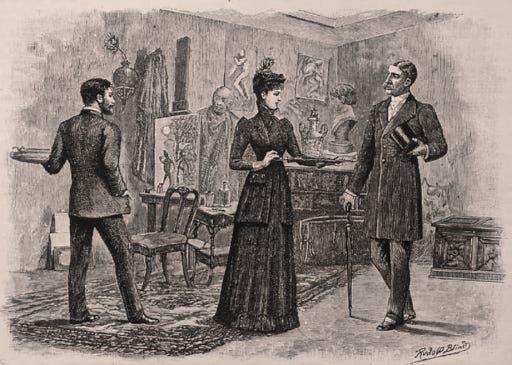

(“The Real Thing,” by the way, is the title of one of James’ more ironic stories, in which a pair of “real” down-on-their-luck aristocrats prove utterly unable to present themselves believable as aristocrats when they try to find work as artist’s models for a society painter. A working-class Englishwoman, Miss Churm, and an Italian immigrant named Oronte, turn out to be much more convincing—”She was a meagre little Miss Churm, but she was an ample heroine of romance.” Reality, in other words, can be an obstacle to its own representation.)

The excerpt from James’ letter is worth presenting in fuller form:

The “historic” novel is, for me, condemned, even in cases of labor as delicate as yours, to a fatal cheapness….You may multiply the little facts that can be got from pictures & documents, relics & prints, as much as you like—the real thing is almost impossible to do, & in its absence the whole effect is as nought; I mean the invention, the representation of the old consciousness, the soul, the sense, the horizon, the vision of individuals in whose minds half the things that make ours, that make the modern world were non-existent….Go back to the country of the Pointed Firs, come back to the palpable present-intimate that throbs responsive, & that wants, misses, needs you, God knows, & that suffers woefully in your absence.

For James, the effort to use one’s modern mind to imagine the workings of a pre-modern one is always wasted; he might be right about that if the goal is always “the real thing.” But is the gap between the “real thing” and “the palpable present-intimate” of fiction necessarily “as nought”? There is always an ironic gap between our representations of the past and our sense of the palpable present; this gap is often filled by a smug knowingness, as seen in contemporary TV shows set in the past: Mad Men comes to mind, or even Cobra Kai, or GLOW. But not all ironies are created equal; when I read a truly great historical novel, such as Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell novels or my beloved Aubrey-Maturin series, I am conscious of the gap between the past and present on the level of allegory, theme, and purpose. In other words, the gap between past and present is on one level what these books are about.

I think for example of the dual protagonists of the Aubrey-Maturin series, each of whom stands before the reader as a representative man of his time. Captain Jack Aubrey is a red-blooded Tory Englishman and a servant of empire, a venerator of tradition and an inspiring leader of men, as capable in a sea-fight as he is hapless in the face of con men and nefarious “projectors” on land. Dr. Stephen Maturin is a Catalan-Irish revolutionary, a doctor, naturalist, and spy who rationalizes his service to the Crown as a means to the end of national determination (he views Bonaparte’s tyranny as a far greater threat to the world than British imperialism—as you know if you’ve read the books, in the Royal Navy one must always choose the lesser of two weevils).

As characters, Aubrey looks to the past, whereas Maturin is far more modern in his attitudes and at times the voice of the liberal establishment that still held sway when O’Brian started writing at the end of the 1960s. O’Brian’s novels are rightly praised for their grasp of the details of the period—he multiplies “the little facts” in the form of his famously baroque nautical vocabulary, which overwhelms the reader with an enchanting mix of strangeness and presumed verisimilitude. Here’s a passage selected more or less at random from the third novel in the series, H.M.S. Surprise:

In the momentary lull of the deepest trough he raced along the gangway, followed by twenty men: a cross-sea broke over the side waist-deep: they ploughed through and they were on the forecastle before the ship, slewed half across the wind, began to rise—before the next wave was more than half-way to them. Men were swarming up the weather ratlines, forcing themselves up against the strength of the gale; their backs made sail enough to bring her head a little round before the sea struck them with an all-engulfing crash and spout of foam—far enough round for the wave to take her abaft the beam, and still she swam.

I am a little fuzzy on what a phrase like “abaft the beam” means, and I don’t much want to look it up—I get the gist, and more than the gist, I get a wonderful sense of reality from a passage like this, and even more so from O’Brian’s dialogue, which moves up and down the social scale with astonishing facility, from drawing-room talk on shore to the officers’ conversation in the gunroom to the pungent language of the common sailors. He has often been compared to Jane Austen for his ability to present a seemingly complete (and drily humorous) portrait of an entire social world. Notably, these novels are set in the same period in which Austen was actually alive and writing, in which her representation of late-eighteenth-century society and consciousness was very much “the palpable present-intimate” that James so highly prized.

O’Brian achieves the palpable largely through the richness of his verbal imagination, as well as his immersion in a formidable array of “pictures & documents, relics & prints.” The intimate is present as well; if you’ve read all twenty novels (as I have, more than once), you will come to feel that Jack and Stephen are intimate friends not just to one another, but to you.

As for the present in historical novels such as these, you might think its absence speaks to their appeal as escapist adventure literature, set safely in another age with no bearing on the present. That escapist quality is what I think many people associate with genre fiction in general, and speaks to why James, and generations of subsequent academics and critics, have been slow to take genre fiction seriously. And yet it’s impossible for me to read these novels without a sense of the history they depict as very much living into our present. For one thing, the books are full of rapturous descriptions of wildlife: few fiction writers are as adept at depicting the natural world, and Maturin’s reverence and excitement when he discovers a new species of tortoise (of course he names it Testudo aubreii) is contagious. But I can’t read about Maturin’s activities and explorations without a lump in my throat for the wholesale destruction of the natural world he’s discovering, a destruction that was already accelerating when O’Brian published the first novel in 1969. Nor can I forget Maturin’s fundamental naivete (both he and Aubrey have a boyish quality that they never entirely shed) in allying himself to the imperial cause, one of the consequences of which will be the pitiless colonization and exploitation of the wide world presented to us with such wonder.

The present is, in other words, very much present to the alert reader when reading a historical novel, and I read this at least potentially as a strength of the genre, not its weakness.

Now here I’ve gone on and on about the historical novel when what I really wanted to write about was science fiction and the possibility of a Jamesian approach to stories about robots and aliens and spaceships. Put another way, I see a lot more continuity between SFF and realistic fiction than is generally assumed.

James’ antipathy to the genre is similarly generally assumed. He feuded famously with H.G. Wells, lamenting the lifelessness of Wells’s more didactic fiction, and was much injured by Wells’ satire of James’ style in a novel called Boon. (This is where the famous image of James’ prose as resembling “a magnificent but painful hippopotamus resolved at any cost, even at the cost of its dignity, upon picking up a pea” comes from.) If you Google “science fiction” and “Henry James,” up pops this amusing little story about a book publisher whose new prize author turns out to be just the front for a novel-writing AI he keeps on his laptop. The publisher ends up pushing both of them in front of a bus in the name of protecting the sanctity of literature.

But let’s remember who Henry was named for: Henry James, Sr. was a religious writer in the Swedenborgian vein, whose unreadable cosmological speculations would probably pair well with Philip K. Dick’s notorious exegesis. It’s probably not an exaggeration to say that the spirit of speculative fiction was something that James inhaled during his anxious and peripatetic education. Certainly he rejected it—and yet he became a fiction writer known for his wooliness, as dedicated as his father to speculation. But it’s the intimate he chose to speculate about, rejecting the cosmological scale of his father’s writings in favor of exploring the intimate consciousness of his characters and the capacity of the periodic sentence to represent it.

I am following up on an intuition hinted at in my previous post that there is more of a continuum than one might suppose between the separate ambitions of poets, science fiction writers, and writers of realist fiction. (Okay, my ambitions.) All imaginative writing is speculative in the sense that it must imagine what it takes to be real but fundamentally inaccessible—the ding an sich of one’s own consciousness (if one is even a little bit Freudian), of the future, or of social life. In that sense a novel like Siri Hustvedt’s achingly sad What I Loved—a realist novel about art’s ability to reframe one’s relationship to marriage, parenting, and loss—is every bit as speculative as one of Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, which imagines the ramifications of a world without scarcity in a far-future universe whose most significant players are artificially intelligent “Minds.” I am reading Hustvedt and Banks side by side at the moment, and while their pleasures are different in texture, and the gravity of their plots hit me differently (I don’t think Banks has the capacity, as Hustvedt does, to make me cry), both of them are intensely speculative about the social and moral possibilities of highly specific fictional constructs—the New York art world in the one case and a fabulous society in which death is more or less optional in the other.

The New York art world is real in a sense that the Culture is not, and yet both novels devote considerable space to speculation. What I Loved is punctuated by detailed descriptions of imaginary artworks, each of which seems to reconfigure not only the narrator’s sense of the inner life of the friend who made them but his own evolving relationship to other significant people in his own life, notably Violet, the artist’s wife for whom the narrator has an erotic fascination. He sees himself reflected in his friend’s paintings and sculptures, as in a funhouse mirror, and becomes more attentive to the mystery of his own desires.

A novel like Banks’ Surface Detail is crammed top-to-toe with imaginary things: aliens that seem to be something like a combination of elephants and A.A. Milne’s Eeyore; spaceships the size of skyscrapers; virtual realities as convincing or maybe more so than the real thing (including a vividly described Hieronymous Bosch-like Hell); etc. It lacks the depth of characterization of the Hustvedt, possibly because the “palpable” of a space opera tends to be backfilled by genre cliches rather than the lived history we can assume for a character like Hustvedt’s narrator, an aging art historian in New York City. The same undescribed interval between our calamitous present and the (in this case) utopian future assumed by Banks is what makes that future believable, at the cost of uprooting its characters from the palpable histories that ought to fill and energize its present. Reading it is certainly a less intimate experience than the one I have with What I Loved; yet I hesitate to say that Hustvedt is “better” or writing in a non-speculative mode.

Maybe it all comes down to scale. The realist novel does tend toward intimacy, very often the domestic—which is why a writer like Amitav Ghosh can claim that realism, with its focus on the moral career of individuals, is singularly ill-equipped to tell truthful stories about our era of globalized climate disruption. As his subtitle implies, and as the IPCC report reinforces, the “unthinkable” cannot be successfully engaged by the same-old models of thought we’ve always had. And so the challenge for the fiction writer now is to engage with the vast scale of our situation so that it has a meaningful bearing on the intimate experience that makes fiction feel truthful, and a useful source of insight into the mysteries that got us here. Put another way, I’m interested at the moment in writing that helps me to understand how we got here, because that understanding helps me to imagine alternatives to the all-too thinkable.

To help me do that, I plan to continue to explore all available modes of the speculative. In my poetry, as for example in my latest book (buy it here), I try to adapt the distinctive languages of particular styles of thought (associated in this case with the likes of Martin Heidegger, Hannah Arendt, Simone Weil, Walter Benjamin, Paul Celan, and others) to imagine what I think of as the twentieth-century’s unconscious and the pressure it brings to bear on the twenty-first. In my more or less realist fiction—such as Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy and the novel that’s coming out next year—I speculate obsessively about the 1960s, the historical moment immediately prior to my own birth, and the ways in which that moment shaped who I’ve become and the world in which I’ve grown up. In my science fiction novels (yet to see print but I hope that will change), I imagine the consequences of American exceptionalism in a climate change-ravaged future-present, but I’m also still very much concerned with consciousness and the ways we might employ technology (and in the broadest sense literature too is a technology) not in ever-more baroque attempts to control nature but to become more attuned to it and to the fuller understanding of ourselves.