1

The fourth chapter of The Far Side of the World brings us, 157 pages in to a 366-page novel (itself what would become the midpoint of a twenty-one volume series), not to any sort of dramatic midpoint but to one of O’Brian’s frequent departures or digressions, this time on the arrival of Stephen Maturin and his bird-fancying friend Parson Martin (why am I only just now noticing the similarity of their names?) into the naturalist’s paradise that is the New World, circa 1812:

Martin clasped his hands as he gazed, uttering some private ejaculations; and Stephen, touching his elbow, nodded towards three trees some way up the river, three enormous cathedral-like domes that rose two hundred feet above the rest, one of them completely covered with deep red flowers.

They took a few more steps through the palms, reaching the white unshaded strand: to the left hand at the water’s edge lay a twenty-foot caiman, contemplating the gentle stream, and to the right hand, full in the brilliant sun there stood a scarlet ibis.

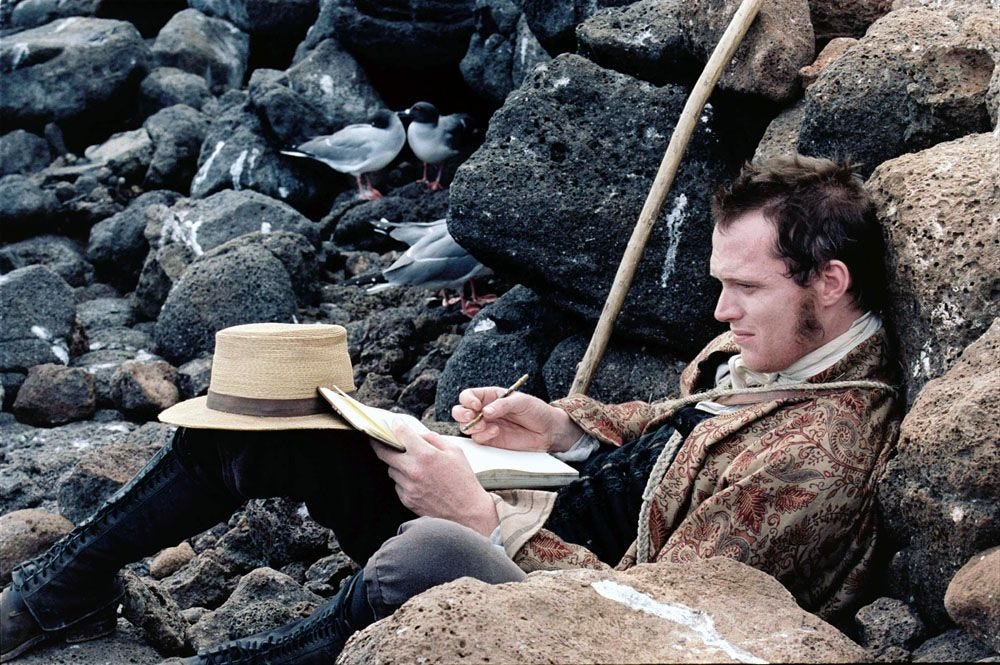

Martin and Maturin fall out of language into overwhelmed reverence for the sheer plenitude of nature on the coast of Brazil, but this is something their author can never do. Instead his choice of words makes it quite clear that in this moment, these nominally Christian men (Martin is an Anglican priest and Stephen, of course, is a Catholic) are worshipping not at the altar of God, but at His Creation. It is one of the brilliant lines of intellectual tension running through this novel, which begins with a Moby Dick-like consideration of whaling and climaxes in the Galapagos, in which the sometimes testy dynamic between Jack and Stephen anticipates the tensions that will play out on the H.M.S. Beagle between Captain FitzRoy and Charles Darwin, nineteen years hence.

What does this scene have to do with the main plot? What does it contribute to the story? Nothing whatever. It simply is, and what is, in the novels of Patrick O’Brian, is beautiful.

2

I have been thinking a lot about the tension between good writing and good, er, novelizing, or I suppose you could simply say storytelling. In a recent Substack, the writer Phil Christman considers the case of a young fantasy writer who disputes the adage that, to be a writer, one must read everything; this writer even goes so far as to label this expectation as ableist. Christman ecumenically proposes that there’s nothing wrong with being a writer whose main preoccupation is story rather than voice or insight or the music of language, who takes their storytelling models entirely from pop culture and not from literature. This is probably the only sane approach to that sort of thing, if one is not simply going to tear one’s hair out, lament the illiteracy of the young, and transform oneself into the archetypal Abe Simpson meme.

A more highbrow version of the distinction between writer and novelist/storyteller is one of the themes of Elif Batuman’s Either/Or, which I discussed a few posts ago. Batuman’s alter-ego Selin wouldn’t dream of rejecting literature, and in particular the great 19th-century novels upon which she attempts to model her life and art. But she does worry that, although no one can dispute that someone who has kept voluminous diaries analyzing her every thought and deed from the age of ten is a writer, that very approach to writing may be antithetical to the demands and skill set required of the novelist. As Selin puts it, “to be obsessed by your own life experience was childish, egotistical, unartistic, and worthy of contempt.” The entire novel, of course, is a slyly structural rejoinder to this attitude, which hinges on the dichotomy between aesthetic and ethical approaches to life.

Perhaps we can try assigning “writing,” with its concern with”your own life experience” to the ethical and “storytelling” to the aesthetic and see what happens. The two novels I’ve published derive much of their energy from the tension between writing and storytelling. Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy divides its protagonist between a noir-style detective called Lamb and Ruth, a young mother often referred to as “the new reader,” who hires Lamb in an attempt to understand her mother’s life and death within the parameters of the novels she reads obsessively. Only about halfway through the novel do we fall into story, when a new narrator, Gustave, tells the story of his inconclusive affair with Ruth’s mother during the May ‘68 student uprisings in Paris. The character of Ruth’s mother—referred to only as M—was inspired by my own mother, a poet and Holocaust survivor who died before we had the chance to really understand each other. The loose baggy monster of the novel form was in this case the substitute for a conversation I’ll never be able to have.

My new novel How Long Is Now is even more openly autofictional, dividing its narrative between the feckless adventures of a writer almost exactly like me in Europe and Morocco and the imaginative recreation of my parents’ courtship in 1960s New York. Once again the Sixties loom large as a decade for me somehow formative, even though I didn’t yet exist (I was born in 1970). Once again the novel is built around an absence, this time of my father, who died of complications from a freak accident in 2018. Both books are shaggy dog stories about grief, in the sense that the story in them—the characters and their actions, the settings, the nominal plots—are more or less open pretexts for the exploration of the experience of loss, which for better or worse in my case takes an acutely literary form. Put another way, if this isn’t too grandiose, I feel myself to be an orphan adopted by literature. This feeling probably has less to do with my parents’ deaths than it does with lifelong feelings of alienation and outsiderness, feelings I suspect essential to and productive of any given writer’s character. They certainly seem to have central to Patrick O’Brian’s.

3

Turning back to the question of writing vs. novelizing, I think of Janet Burroway, perhaps the most popular and influential author of creative writing textbooks, whom I wrote about a while back in a post inspired by Netflix’s The Chair (nope, still haven’t seen it). I was a bit startled, when I first picked up Writing Fiction to use as my textbook for a course I was about to teach, to read these paragraphs from her chapter on plot. The first is about storytelling and its supposed function:

It seems likely that the earliest storytellers—in the tent or the harem, around the campfire or on the Viking ship—told stories out of an impulse to tell stories. They made themselves popular by distracting their listeners from a dull or dangerous evening with heroic exploits and a skill at creating suspense: What happened next? And after that? And then what happened?

There isn’t a lot of insight to be found in Burroway’s tautological explanation of storytelling, but there is a hint of disdain for what we might call storytelling’s ethical function—not ethical in the sense of the right thing to do, but in the sense of ethos, building a character, as in rhetoric. Storytellers tell stories to make themselves popular—carving out a social role for, it’s implied, people who might not have another one. And they derive their popularity from their powers of distraction from dullness or danger. There’s little or nothing here to do with art as most of us understand it. In the next paragraph, Burroway shows her cards:

Natural storytellers are still around, and a few of them are very rich. Some are on the best-seller list; more are in television and film; some are in comic books and video games. But it’s probable that your impulse to write has little to do with the desire or skill to work out a plot. On the contrary, you want to write because you are a sensitive observer. You have something to say that does not answer the question What happened next? You share with most—and the best—contemporary fiction writers a sense of the injustice, the absurdity, and the beauty of the world, and you want to register your protest, your laughter, your affirmation.

My feelings about this are complicated, to say the least. On the one hand, I react negatively to Burroway’s snobbery, and what comes across as writerly ressentiment for the “natural storytellers,” a few of whom “are very rich.” (Writing Fiction is in its tenth edition, and I’d bet anything sells better that all of Burroway’s novels put together; is that the wrinkle here? Those who can’t do, teach.) To denigrate storytelling as distraction is to deny its pleasures—to deny, in effect, that it has its aesthetic side, without necessarily being “art.”

On the other hand, I feel directly addressed by Burroway—even more to the point, my younger, undergraduate, Selin-like self feels addressed. For when I brought my writerly aspirations to college, thirty-odd years ago, I knew that I was shit at plot, which was the one thing nobody seemed to know how to teach. That’s a large part of why I became a poet, actually, because I couldn’t see how to bring my novelistic aspirations into line with how clumsy and predictable the plots I sketched out in my notebooks always turned out to be. (I had yet to learn the art of discovering plot through writing, rather than planning it out in advance; I am, it appears, a born pantser.) I was a sensitive observer, not a storyteller, I thought—naturally poetry became my thing. It took decades for me to discover the fascination of the dialectic between ethics and aesthetics, storytelling and writing, that Burroway wants to, well, bury.

For Burroway, plot is the spoonful of sugar that makes the sensitive observations go down. “Readers,” she complains, “still want to wonder what will happen next, and unless you make them wonder, they will not turn the page. You must master plot, because no matter how profound or illuminating your vision of the world may be, you cannot convey it to those who do not read you.”

Are the pleasures of plot a necessary evil, then, to be mastered in a spirit of distracting readers from what you’re really up to? Or is plot merely the source of pleasure to which its easiest to point—as what a given story is “about”?

4

For readers of these posts it should be obvious by now that I consider Patrick O’Brian, aka Patrick Russ, to be something of a spiritual kinsman. By all accounts O’Brian was a lonely man whose greatest achievement centers on the relief from loneliness found in the friendship of two men who couldn’t be more different, centered in a floating community where they can be more at home and more themselves than is possible in their supposedly native lands. O’Brian is lauded as a storyteller—”the best Yarn-spinner in all the Fleets,” as Thomas Pynchon put it. And yet the pleasure of “what happens next” has not been central to my experience of reading him for a very long time—such a pleasure can hardly be central to rereading as opposed to reading. If anything, the usual source of pleasure is reversed, as I become pleasurably conscious of a character or scene that I’d forgotten before it occurs—a kind of belated re-anticipation. This is why I have so little patience for the fear of spoilers, because what happens has never interested me as much as how and why.

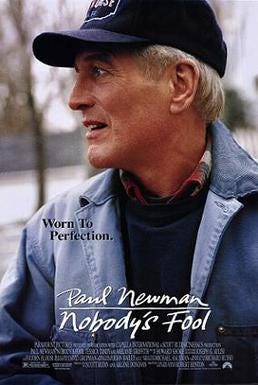

No—I tell a lie. Of course there’s pleasure in finding out what happens in a novel. I just read Richard Russo’s Everybody’s Fool, his sequel to Nobody’s Fool (one of the rare novels whose film adaptation is as rich with pleasures as the book). Russo is a consummate storyteller, if a bit afflicted by sentimentality and a tendency toward caricature (but so was Dickens). As a sequel, the experience of reading Everybody’s Fool offered me a curious mix of the pleasures of reading (finding out what happens) and re-reading (becoming re-acquainted with familiar characters). But although it’s what they still call a literary novel, oriented more toward character than plot, that plot is hilarious and suspenseful, centering on the hapless police chief Doug Raymer’s increasingly wild-eyed quest to discover the identity of his dead wife’s lover. I found it to be a page-turner, consuming the whole thing in 48 hours, and turned to the last page with a silly grin on my face and moistness in my eyes. The guilty were punished, the all-too-human (Russo’s version of virtue) rewarded. Yet I feel sure that the granular pleasures of re-reading this novel would not equal, much less surpass, the intense pleasure of reading it. But I can’t say the same of The Far Side of the World.

5

Viewing the screen adaptation of a novel is another form of rereading, I suppose, and I’ve watched Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World nearly as often as I’ve read the two novels jammed into one that director Peter Weir drew upon to make the film. It’s easy to dwell on what’s missing from the film: Stephen’s intelligence career, any women whatsoever, the character of Parson Martin, and any land aside from the Galapagos. Paul Bettany is far too tall and handsome for Stephen, yet he persuades us with his sudden shifts from distraction to concentration and back again—he’s also brilliantly costumed, and convincing with his cello. Russell Crowe is perfect as Jack, though I should have liked to see a bit more of the character’s goofy side, and it’s delightful to see minor characters like David Threlfall’s Preserved Killick and Billy Boyd’s Barret Bonden so convincingly embodied. The confinement and sense of danger aboard ship are effectively conveyed, and it’s fun to see Jack attempting some of his best ruses (such as the floating rafter hung with lanterns to deceive a pursuer by night). Stephen, meanwhile, pulls off his two most remarkable feats of surgery from the series (the trepanation of the gunner from Master and Commander, the self-surgery from H.M.S. Surprise) and is appropriately vexed by Jack’s failure to keep his promises to give Stephen time to botanize. There’s some thrilling spectacle and the great guns get plenty of exercise. The most genuinely O’Brian-esque touch, however, is the use of music to characterize each man: when Stephen is alone, we hear his cello; when Jack attacks, the violin takes the lead; when they come together to play in the main cabin, it’s their bond made audible, transcendental.

I like the movie a lot, but for me it succeeds primarily as proof of concept for the Aubrey-Maturin television series that will likely never be made, given how expensive it would be to do the thing properly, CGI or no CGI. The pleasure such a series promises is the pleasure of rereading, the pleasure of Patrick O’Brian’s “is”: to see again, in a new medium, characters and places and situations with which we are already intimately familiar. This seems about as far from real art and genuine aesthetic experience as we can get. In Coleridge’s terms, this is a scenario of fancy (fantasy), the re-arrangement of already existing intellectual property. The novels, n the other hand, are works of imagination, contributing (as R.P. Blackmur said of poems) to the store of available reality. When we adapt, when we interpret, when we re-read, we do the former and not the latter. Don’t we?

Truth and fiction, writing and novelizing, the ethical and the aesthetic. It’s finally the and that compels, the sliding between opposites like the pitching of the Surprise in a heavy sea. Because I have a Cartesian turn of mind, I’m forever fretting about which side of the line I fall, or a particular piece of writing falls. Why do I always forget that the most intensely personal can manifest in something invented? Or that even when I focus deliberately on story—as in my as-yet unpublished science fiction novels, or even more so the television scripts I’ve been working on—writing, the keen and sensitive observation of people and events as focused and refracted through diction, syntax, etc., remains the necessary medium between me and “real life”?

These books are alive, and I’m at my most alive in them.

Speaking of writing from life, if you haven’t already done so, please check out shelter in place, my collection of one-hundred-word responses to the pandemic, composed daily over one hundred days, from March 18 through June 25, 2020. It’s available as a free ebook to be downloaded from my website; you can learn more about the project and see sample pages here.