(Author’s note: I am taking a break from writing about Patrick O’Brian because this is my newsletter, damnit, and I can write about whatever I want. I’m sure to get back to Jack and Stephen eventually, but in the meantime, enjoy this review of Paolo Sorrentino’s latest film.)

The Hand of God is really two films: a self-consciously Fellini-esque romp of grotesquerie and eroticism that’s all in the family, and a somber, introspective coming-of-age story. It’s neatly divided in the middle (spoiler alert) by the death of the protagonist’s parents from carbon monoxide poisoning at their holiday condo; their younger son, Fabio (whom everyone calls by the diminutive Fabietto) was supposed to be there with them, but stayed in Naples to watch Diego Maradona play for the home team. The hand of god, in other words, saves his life. The title phrase is deeply ironic; Maradona used it to describe the goal he scored during a quarter finals match against England for the 1986 World Cup: his hand touched the ball, an illegal move that went undetected by the referees. “The hand of God” in this case is an appeal to divine intervention that is also fundamentally fraudulent. This divide, between the divine and the profane, between the transcendent and the scandalous, between fantasy and reality, defines the film, as it has defined Sorrentino’s career and no doubt his life. The film is autobiographical; his parents really died like that; at the end, Fabietto/Fabio/Paolo boards a train and heads for Rome to pursue the destiny that will include the film we have just seen.

Because I’d read an interview with Sorrentino before I watched it, I don’t know what it would be like to see this film without knowing about the terrible twist at its center. The first half appears mostly as a lushly indulgent celebration of Naples and the mostly happy and raucous life of Fabietto’s large and exuberantly vulgar extended family. The second half is quiet, nearly solitary, as the abandoned young man who will grow up to become the director wanders the suddenly deserted city, accumulating piecemeal the experiences of transient connection that will carry him into his adulthood. A series of catalytic encounters winds through the film: the exciting and disturbing nudity of his voluptuous, mentally ill Aunt Patrizia; the distant yet somehow intimate figure of Maradona; Fellini himself (Fabietto’s older brother Marchino, played by Marlon Joubert, auditions to be an extra in of his films, only to be turned away by the great man for having a face “like a waiter”); the aged Baronessa who lives upstairs and who eventually relieves Fabietto of his virginity; the cigarette smuggler who offers him friendship but is then lost to prison; and finally the obnoxious film director Antonio Capuano (Ciro Capano), who batters the young man with aggressive platitudes that nonetheless add up to a kind of artistic initiation, throwing down the gauntlet of his challenge: “Do you have something to say?”

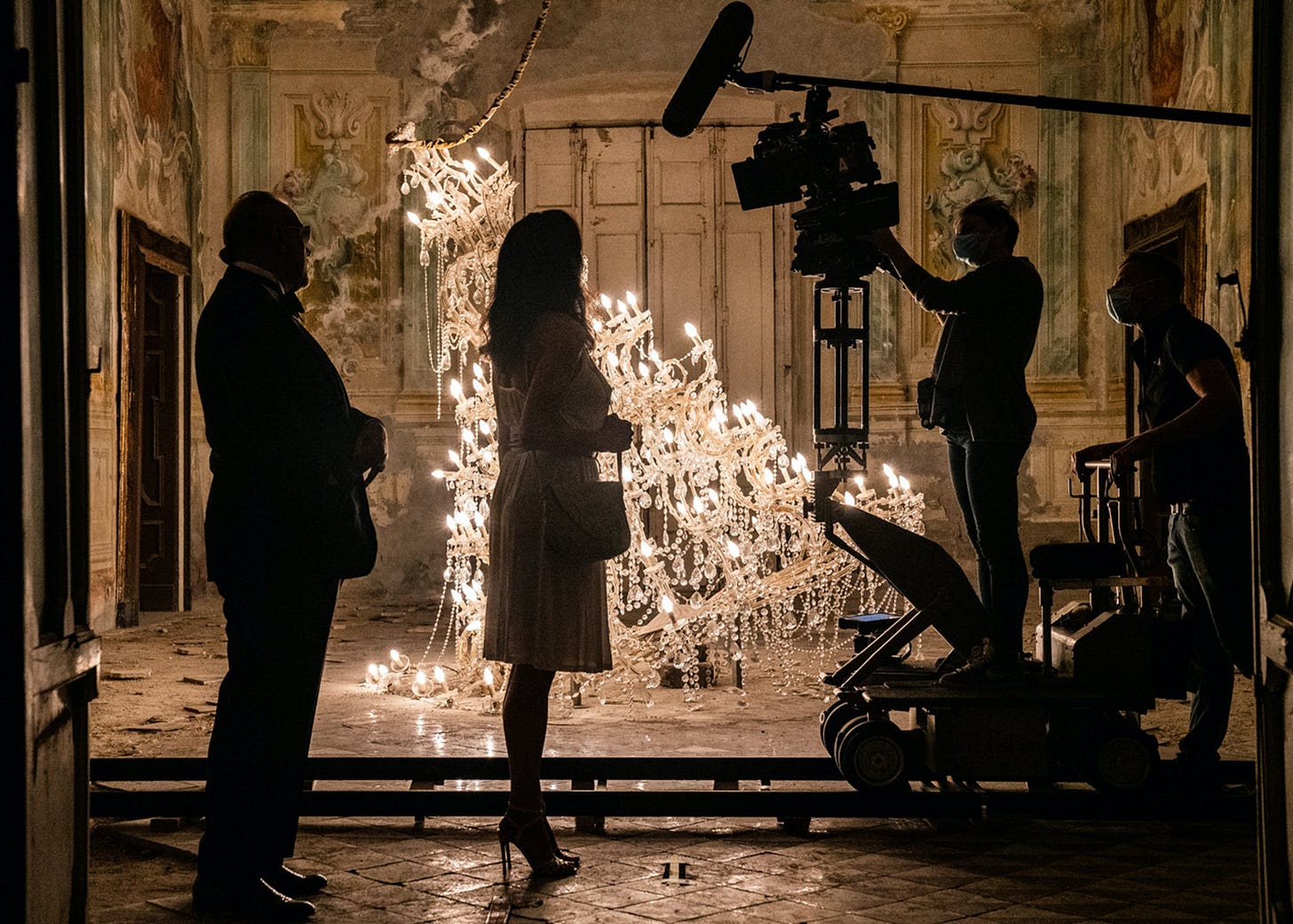

There’s little wisdom on offer in what the characters say to each other: it’s mostly banalities, insults, pranks and jokes. Faces and embraces and the lush yet stricken landscape around Naples do the work of quickening whatever might be slumbering in Fabietto’s soul. One of the film’s many vatic images is that of a man hanging suspended by his ankles in the Galleria Umberto I, a Tarot-like image of meditation, sacrifice, and potential energy. Fabietto’s mad aunt is the touchstone—a woman injured by life, unable to get pregnant, quite possibly a nymphomaniac. When the film begins we see her plucked from a bus stop by a distinguished-looking older man being driven in an ancient Rolls Royce; he claims to be San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples. He whisks her away to a ruined palazzo whose centerpiece is a fallen chandelier, leaning like the Tower of Pisa, where she is blessed (and slipped some cash) by a cowled figure called “the Little Monk.” The saint gooses her and says, “Now you can get pregnant.” Which she does in due course, only—we learn this much later—to have a miscarriage after another in an endless series of violent fights with her husband, who accuses her of turning tricks.

It’s an ambiguous frame for the movie as a whole. Reality is terrible, Fellini is said to say; I prefer the dream of cinema. In cinema the delusions of a character like Patrizia can be realized, but only temporarily; she must return to earth unconsoled. The last we see of her is through the upstairs window of an insane asylum, bidding a silent farewell to her nephew standing in the desolate courtyard below before he departs for Rome and his future. She is the one of the secret hearts of the film, its betrayed saint.

The other is Fabietto’s mother Maria (Teresa Saponangelo), whose adoring marriage to her husband, a banker who claims to be a Communist, is shadowed by his long-term affair with another woman. She’s a prankster, a juggler of oranges, a Fellini-esque sad clown, whom we glimpse at one point watching tenderly over her son as he sleeps. When he learns of the affair and hears his mother’s howling grief, his empathy completely captures his body; shaking and trembling, he is wrapped in the arms of his feckless but loving brother. I was terribly moved by the first half’s scenes of family happiness and torment, equally precious for their ephemerality, their perishability. The repeated image of Fabietto driving his parents on his motor scooter, sandwiched together behind him, screaming in glee, is as powerful an image as I can think of for the persistence of parental love. Once they protected him; after their premature deaths he must ride into the future alone, with only the memory of their touch.

I took this film personally. While I wasn’t orphaned at the age of sixteen, as Sorrentino was, I lost my mother to cancer when I was twenty-one, and I’m still getting over my father’s death in the wake of a freak accident three years ago. Loss as a spur to creativity has interested me for a long time. Toward the film’s end, Fabietto tells Capuano that he wishes, like Fellini, to escape from the terribleness of real life into the fantasy of cinema. Capuano rejects this: for him cinema is life. “Without conflict, you don’t progress,” he tells his protege, echoing William Blake in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.

From these contraries spring what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys reason; Evil is the active springing from Energy.

Good is heaven. Evil is hell.

The Fabietto of the film is good, passive, a reasonable observer (at one point he tells his mother he wants to study philosophy), but he exists in a film controlled by the eye of his older self, an eye for the active, the explosive, the repulsive. The Hand of God is a Proustian swipe at the past recaptured, which is the real purpose of a cinema for which the dream life is the real one. The structure of the film is simple: a fall from the heaven of childhood into the hell of adulthood. But there are no filmmakers in heaven.

Our last image of Fabio—Fabietto no longer—is on the train to Rome. A vision of the Little Monk standing on a train platform, cowl down, revealing an impish smiling face, yields to Fabio through the window, listening to the Walkman he’s carried like a talisman throughout the film. For the first time, we are allowed to listen in to what he’s hearing: Pino Daniele’s song “Napoli É” (Naples Is). The song that will carry him away to Rome and into a future conditioned by his past:

Napule è mille culture

(Napule è mille paure)

Napule è nu sole amaro

(Napule è addore e' mare)

Naples is a thousand cultures

(Naples is a thousand fears)

Naples is a bitter sun

(Naples is adoration and sea)