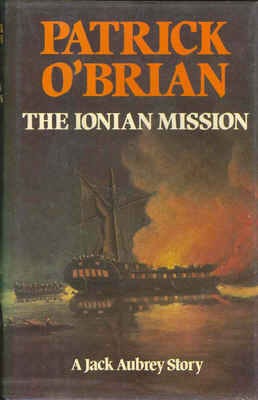

Nothing much happens in the first half of The Ionian Mission, the eighth novel in the Aubrey-Maturin series, and I must confess that that’s just the way I like it. My favorite film subgenre is the hangout movie, a la Barry Levinson’s Diner or Richard Linklater’s Everybody Wants Some! These are the kinds of movies in which a group of likable characters do nothing in particular, shooting the breeze and getting into low-stakes mischief. Such films may have a languid quality to them, but their attractions are rooted in their characters; as Quentin Tarantino, who seems to have coined the term, puts it, “There are certain movies that you hang out with the characters so much that they actually become your friends.”

It should be clear to anyone who reads these little dispatches that I’ve come to think of Jack and Stephen as friends, and of Stephen in particular as a kind of second self (though I am no more a naturalist or secret agent than I am a sailor). The sheer length of the Aubreyad permits for a good deal of downtime, during which we come to know Jack, Stephen, and the characters around them more and more intimately, enjoying their foibles, their wit (or in Jack’s case, his endearing attempts at it), and not least, their enjoyment of one another. Even the most action-packed novels, such as The Mauritius Command, find leisure for banter, for dinners in the gunroom and the captain’s cabin, for observing wildlife, for devising a new trim for the sails or a new plan for the midshipmen’s education, and above all, for music—the initial and continuing hinge between the man of action and the man of contemplation.

That said, The Ionian Mission is more of a hangout novel than the others, with a very slow build from the opening pages in which Jack and Stephen take leave of their domestic affairs (surprisingly happy if unconventionally arranged on the part of the recently wed Stephen Maturin; heavy with ominous legal entanglements on the part of Jack) to take ship aboard H.M.S. Worcester, a wall-sided and lubberly ship of the line taking part in the endless blockade off Toulon. A full 160 pages go by before anything like a major plot point arrives: Jack is sent on what appears to him to be a simple errand that is actually part of a complex scheme to provoke the French into violating the neutrality of the neutral African port of Medina. The scheme fails, and a disgruntled Jack goes back to blockading. More significant to the feel of the novel than this feint at plot is the separation of Jack and Stephen: Stephen is off on a secret mission to the mainland, leaving us in the company of Captain Aubrey and a bad cold. Somehow O’Brian is able to portray the boredom and frustration of Jack and his blockading crew without ever once himself being boring or frustrating, even as we share Jack’s growing feelings of isolation in the absence of his particular friend.

Before that happens, we are treated to a leisurely iteration of what have become stock elements in the series, present to a degree in nearly every novel. These stock elements include:

Jack’s assignment to a new command, wherein he must immediately deal with the ship’s deficiencies in seaworthiness or with the problem of manning her with competent hands, sometimes both;

Stephen comes aboard in some state of lateness or disgrace, embarrassing Jack;

The new crew is trained up to Jack’s high standard of gunnery: three rounds in five minutes is presented as the key to victory in most situations;

Stephen walks into the gunroom (or in the case of a ship of the line, the wardroom) and takes the measure of his new shipmates; some of them will become friends while others prove to be inimical sources of irritation;

A minor emergency at sea caused by the weather or the enemy or both, during which Jack is able to take the measure of his new ship and crew and perhaps help bring them more solidly together—this is often recounted in the form of one of Jack’s letters to Sophie;

Stephen sustains some sort of injury or at the very least a thorough soaking;

Tensions on the lower deck, generally played for laughs, are contrasted with tensions among the officers—a lieutenant who falls out in some way with the captain.

Jack must negotiate his relationship with his superior officer—typically an admiral in some way compromised by venality, unscrupulousness, or, in the case of The Ionian Mission’s Admiral Thornton, physical decline.

All of these elements are present in The Ionian Mission, dilated upon so that one reviewer summarized the novel as “splendid adventures at a stately pace.” This leisureliness is especially striking given that, with the end of the previous novel, we have more or less come to the end of the regular chronology and now enter the strangely subdivided period that amounts to several concurrent 1812s. There simply isn’t time enough in the calendar for all the adventures remaining to Jack and Stephen before Napoleon is exiled to Elba in 1814. We have therefore rather literally entered a period of extra time, as in a game of football. Perhaps that accounts for the book’s almost startlingly frenzied conclusion, ending very nearly in the middle of a sea fight with a ruthless corsair.

But here I want to stop for a digression on the Aubrey-Maturin series as art, with reference to a recent article in The New York Review of Books that gave me considerable pause.

2

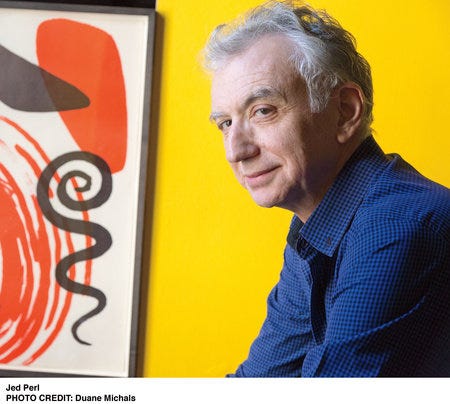

In “The Imaginative Imperative,” Jon Banville summarizes art critic Jed Perl’s new book Authority and Freedom as a defense of high art—a term, Banville notes, that when used “would today be a heroic and certainly provocative gesture.” He quotes a brief, wonderfully succinct passage from Perl that got me thinking about that hoary old distinction between what used to be called mass culture and the high bourgeois variety:

The art in popular culture has everything to do with creating a work that catalyzes a strain of feeling in the mass audience. High art operates in a completely different way, for each viewer comes to the work with the fullest, the most intense, the most personal awareness of the conventions and traditions of an artform.

The distinction depends less, perhaps, on the artist’s intention and more on the qualities of their audience—the qualities but also the quantity. A mass audience in its multiplicity cannot evade the arithmetic of the lowest common denominator. The other kind of audience is more individualized, depending, as Banville puts it, on having “educated yourself, in highly specialized forms of language, signs, and sounds.”

The education of the audience is key to appreciating the quality of an artwork that, as Banville puts it, “to an extent always withholds itself, conceals itself, in the plainest of plain sight; the work of art is at once there and not there.” Perl calls this quality “the enigma of the work itself”; out of this enigma, an un- or anti-presence that only the educated reader or viewer can discern, stems what Perl and Banville might untimely term the autonomy of art.

Let’s return, for a moment, to Patrick O’Brian. Are the Aubrey-Maturin novels pop culture, high art, or something in between? They don’t reach anything close to the same mass audience as James Patterson or Stephen King, but they probably sell better, year in and year out, than most works of literary fiction, and they inspired at least one very good Hollywood film, making $212 million at the box office (Wikipedia calls this “a moderate success”). Fans of the series are numerous enough to sustain any number of discussion threads, fan sites, podcasts, etc. At the same time, people like me are forever comparing O’Brian to Jane Austen, James Joyce, and other avatars of high literary art. Maybe it would be more accurate to call O’Brian’s writing “middlebrow,” a mid-century term of opprobrium for watered-down modernism that demands less of its audience while flattering its intelligence. But that doesn’t quite describe the work of a writer whose formidable erudition, complex prose, and narrative cunning lays out so much on the surface for novice readers while inviting endless rereadings (or “circumnavigations”) by fans.

“Fan” is an interesting word to apply: did you know that it’s short for fanatic? (The Latin fanaticus means “insanely but divinely inspired,” which sounds about right.) Marvel movies and comics have fans; Star Wars has fans; The Sopranos and Breaking Bad have fans. But autonomous artworks do not. People may call themselves fans of Ulysses or Virginia Woolf or John Ashbery, et al, but there’s always a whiff of irony to the claim. Fan culture has little tolerance for the engima of the artwork that Perl describes; fans, and the corporate authors that cater to them, are forever filling in backstories and plot holes for the sake of generating new product. I loathe the Star Wars prequels, but at least they seem to have derived from an honest narrative impulse on George Lucas’ part, and there’s a kind of strangeness to them that suggests an individual’s authentic point of view. The same can’t be said of the more recent trilogy (to say nothing of the metastatizing TV shows on Disney+), which is a naked retread of the original films, its spasmodic gestures toward new territory (in The Force Awaken) as ruthlessly suppressed by the final film as the Soviet commissars who fell out of favor with Stalin.

I’m sure the Aubrey-Maturin series has generated fan fiction, and no end of slash fiction, but so far at least no one has crept forward to offer anything like an “official” extension of the Aubrey-Maturin books, or written prequels to explore, say, Jack Aubrey’s adventures while a foremast hand, or Stephen Maturin’s experiences as a medical student in Paris. Maybe the status of a work of art—highbrow or lowbrow—rests entirely in the hands of the audience, and Patrick O’Brian seems to have been lucky in his. People live for and in these books, but they seem content to respect and admire its lacunae, its narrative mysteries and elisions, like the duel between Jack and Stephen that threatens so menacingly in Post Captain only to dissolve in displaced official violence. “Come brother, come. There is too much blood here altogether.”

3

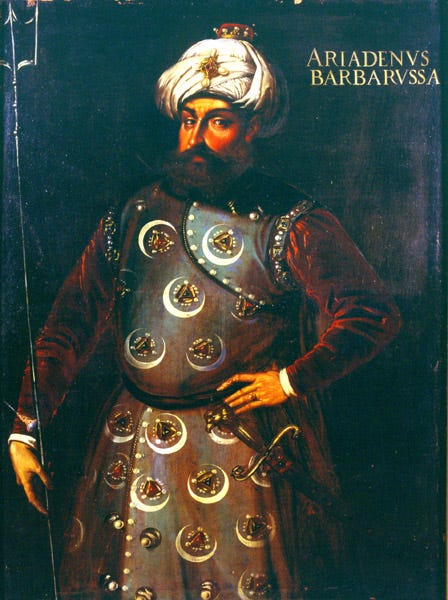

By a curious coincidence, that line is echoed by the last sentences of The Ionian Mission, in which the action become frenetic as though to make up for the deliberative hang-outness of the first half or so: “‘You had better get back to the barky, sir,’ said Bonden in a low voice, tucking the ensign and the other officers’ swords under his arm. ‘This here is going to Kingdom Come.’” “This here” is the Torgud, a Turkish frigate that the Surprise defeats in furious battle at the novel’s end. This is the climax of the the late-arriving titular mission, a journey to the Seven Islands on the Ionian coast to take the measure of three potential allies (beys nominally loyal to the Turkish sultan) who, in return for cannon, will help the British turn the French out of Corfu. One, Ismail, is unimpressive; one, Mustapha, is little better than a pirate (yet Jack likes him instinctively, and I think we are meant to see Mustapha as a kind of second self to the Jack who is so often described as having “a fine piratical gleam” in his eye); the third, Sciahon, is allied with Father Andros, an Orthodox priest who seeks to defend the (fictional) port of Kutali in which Christians and Muslims co-exist more or less peacefully. There are any number of petty utopias in the Aubrey-Maturin novels: small communities, afloat and otherwise, that seem to exist outside the prevailing violent ideologies summed up by the phrase “Napoleonic wars.” Kutali is one of them.

Jack’s instincts lead him to choose Sciahon, much to the frustration of Professor Graham, a moral philosopher and, as we discover midway through the novel, a colleague of Stephen’s in the field of intelligence. Much of the humor of this particular novel derives from the byplay between Stephen and Graham, who as Catalan-Irishman and Scotsman each stand somewhat apart from the sheer Englishness of the Royal Navy; but Stephen is a natural philosopher with a wicked sense of humor, and Graham is a humorless moral philosopher who takes everything said to him literally. The hang-out climax of the novel precedes the action climax: Graham and Stephen are among the hearers of a poetry contest in which Lieutenants Mowett and Rowan face off, each reciting poems that their audience judges more for their nautical accuracy than their prosody. Jack, Solomon-like, splits the decision: “I find that Mr Rowan carries the day as far as poetry in the classical manner is concerned, whereas Mr Mowett wins for poetry in the modern style.”

Jack’s instincts are sound, at least when it comes to matters of naval strategy, and when Mustapha captures the British transports carrying the cannon intended to defend Kutali, Jack and the Surprise set out to intercept him. It’s a furious fight—one ship against two, for Mustapha’s startlingly well-armed frigate the Torgud has a sloop for a consort. But the Surprise prevails, not least because Jack had been aboard the Torgud when Mustapha was wooing him, and took note of the ship’s brass cannon: “If you keep on firing at this rate, they melt. They are pretty, to be sure; but they cannot keep it up.” As always, battle melts and dissolves ill feeling and self-discontent; Jack had felt humiliated by his failure to engage the French in Medina, and a good honest fight is the best remedy he knows for the blue devils. “His heart was bubbling high: that old splendid feeling of more, far more than common life.” I’m reminded of something Robert E. Lee is supposed to have said during the Civil War: “It is well that war is so terrible, else we should grow too fond of it.”

The novel ends in medias res, with Mustapha’s defeat—and this may signal a subtle transition in how O’Brian thought of his project, now eight novels in. The novels may sometimes move slowly as we hang out with a subplot or enjoy a poetry contest, but we swim in the currents of macro-plots that extend beyond the boundaries of any single novel. It was back in the fifth novel, Desolation Island, that we were introduced to the character of Andrew Wray, whom Jack caught cheating at cards; the Acting Second Secretary of the Navy has hovered in the background since then but will encroach on our heroes more definitively in the next novel and remain a primary antagonist until novel 14 or so. The existence of such a macro-plot elaborates and extends the tension of each novel, like the long cable that the Surprise lays up the mountainous streets of Kutali for the purpose of elevating cannon to the highest battlements. Sometimes this plot moves slowly, so that the novels enjoy little more than steerage way—but plenty of time for the characters to, well, character. And at other times, as at the conclusion of The Ionian Mission, we are launched pell-mell into action. How difficult it must have been for its first readers to wait for the next installment!

I was pleased to learn that M.G. Stephens, a prodigiously accomplished writer of my acquaintance here in Evanston, had agreed to read my new novel, How Long Is Now; I was even more pleased when he wrote a new blurb for it! Here’s what Mick has to say:

Joshua Corey writes an impeccable prose that resonates with echoes from the past, even as these echoes propel his narrative onward in the present and beyond, into the future. But that is not all. This is the Portrait of the Artist as a Jewish American male in the early years of the 21st century. His characters hail from a kind of ideal America where people read books and esteem a good education, which in no way absolves them of the tragic rhythms of action that surround their lives. This is the first contemporary novel that I've read in which I have gone back and re-read a paragraph—because it was so good—and not once but several times.

Ain’t that elegant? If you want to read and re-read my paragraphs, please consider purchasing your own copy by clicking on the image below:

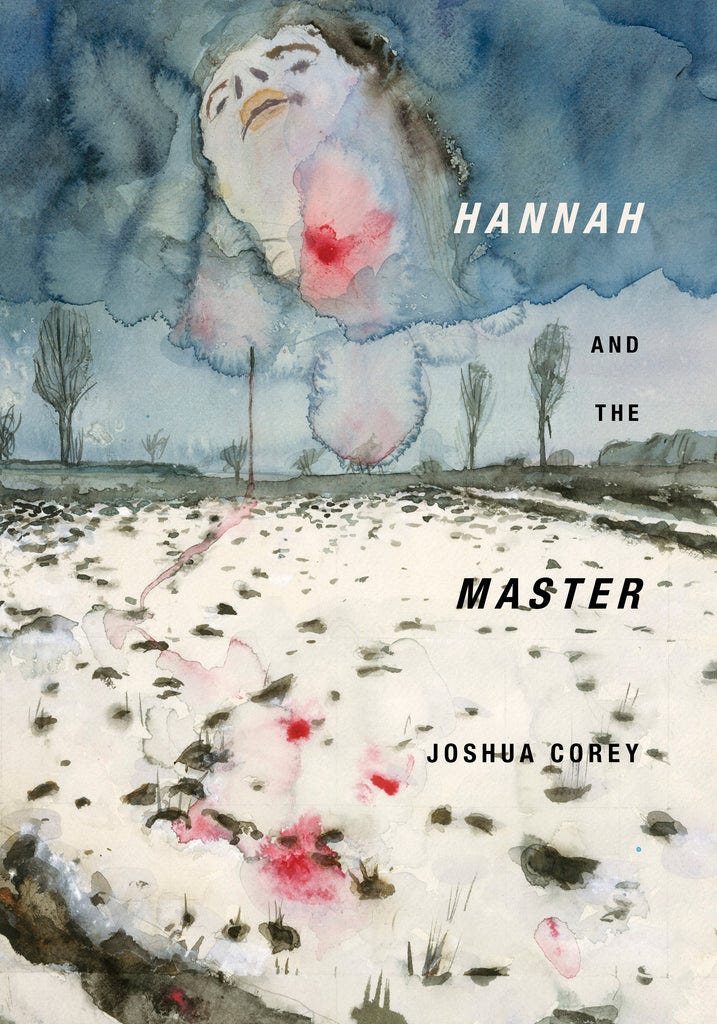

If you want to see what happens when I get really weird, you might check out my most recent poetry book, Hannah and the Master, a kind of speculative masque on the topic of Hannah Arendt and Martin Heidegger’s notorious love affair, and its implications for our era of resurgent fascism. You can read an excerpt here or just buy the thing (check out the wonderful cover, courtesy of the great German painter Anselm Kiefer) by clicking below:

And if by chance you have read either of these books and want to help a fella out, please pop by rhymes-with-Glamazon or Goodreads to rate it and/or write a review. Give those pesky algorithms a nudge for me!

Tomorrow I start teaching Shakespeare for the May summer session at Lake Forest College—first time I’ve had the privilege of doing an entire course on the Bard. I’m a little nervous, but I also feel lucky as hell. I mean, Shakespeare! He’s no Patrick O’Brian, but he’s pretty good. I’ll let you know how it goes.