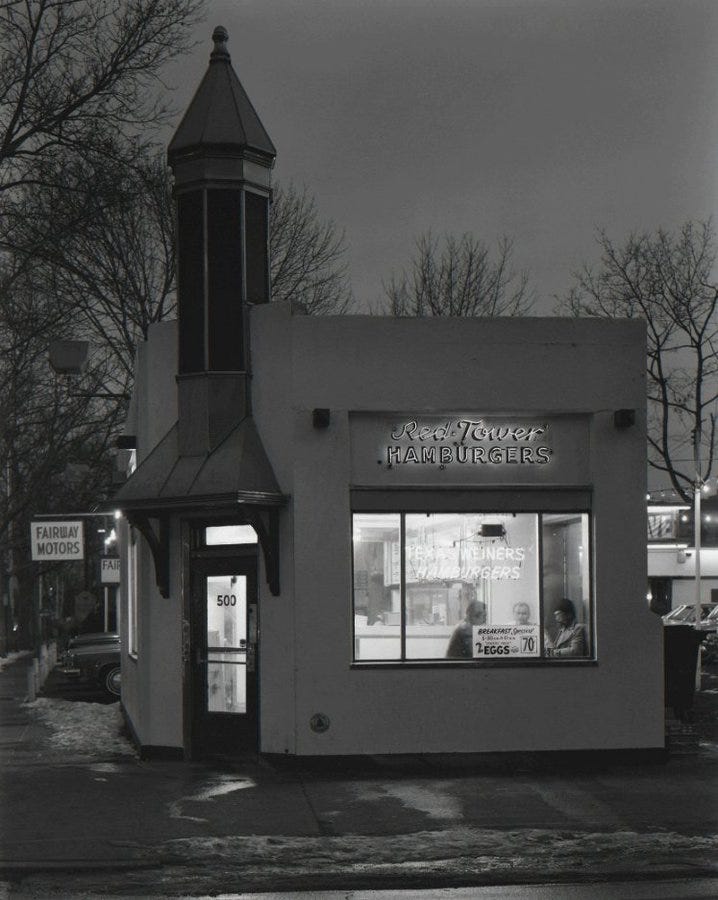

The photo above I encountered randomly on my Twitter feed yesterday; it’s a photograph of the Red Tower, a hamburger shack in Plainfield, New Jersey, where I did part of my growing up. My dad took me there pretty often, at around the same time the picture was taken. To encounter it in a social media feed, with no context, delivered to me a small Proustian shock. I remember the greasy smell of the place, the laminated counters, the fizz of the soda machine and the hiss of meat on the grill, the jukebox full of 45s into which I would feed Dad’s quarters, hunting for the hits of that era: Hall and Oates, Blondie, Stevie Wonder. The burgers came, I think, wrapped in white waxed paper, and the fries were hand cut with the skins still on; the ketchup came brandless in one of those red cylinders with the nozzle on top, looking like nothing so much as the Red Tower itself. What does this memory mean? What does encountering this photo on a random Tuesday, arresting my mindless scroll, mean? Is this a story about me and my dad, just the two of us, indulging our love of comfort food on a Saturday afternoon in the summer of ‘81, when I was ten? Is that enough for a story? Maybe it’s nothing, nothing at all, just a dead moment brought back to life, a bubble in the stream that will soon submerge again, or pop, nothing more than air.

In his 1927 book Aspects of the Novel, E.M. Forster made his well-known distinction between story and plot. Story, Forster says, is a sequence of events: “The king died, then the queen died.” Plot, on the other hand, establishes causality: “The king died, then the queen died of grief.” One thing causes the other, and as a result, the sequence of events becomes meaningful. Without plot, life, like history, is just one damn thing after another.

Fifty-two years and three days ago, I was born to my Chicago-born assimilated Jewish father and my Budapest-born Holocaust-survivor mother at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. A dreamy, unathletic, much picked-on kid, I grew up with the pervasive sense that my life, and all of my experience, was random, a by-product of titanic causes that predated my birth. In my early teen years I became obsessed with World War II as it was filtered to me by two different yet related sources: Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five and the many books on the Holocaust that my mother had accumulated, which I would slip from her bedside to my own. Billy Pilgrim, unstuck in time, and the incomprehensible mechanized cruelty of the death camps, confirmed my belief that World War II was the crucible of chaos from which I had somehow emerged blinking into Ronald Reagan’s what-me-worry America. The war, scarcely distant in time, manifested in my mother’s inability to get out of bed some mornings, in the number tattooed on my Grandfather Ernest’s forearm, and seemed to somehow ratify or confirm what I felt to be my own powerlessness. Like many Americans, I mistook my knowledge of the war for an understanding of history itself; unlike most Americans, the lesson I took from it was not of America’s righteous power but of the cruelty that inevitably results when people gather as a body (a church, a political party, an army) and turn themselves into machines. Had I been born thirty years earlier in Europe, as my mother had been, I would have been marked for death, not for any quality I could claim as my own but simply for being Jewish, whether I was observant or not. The infinitely more mild yet still excruciating persecution at the hands of my more muscular and well-adjusted peers struck me, in my egoism, as a logical extension of my grandparents’ fate.

Life then as I understood it was just one damn thing after another, and it was a matter of pure chance whether you lived or died. I had, therefore, a very difficult time grasping the concept of causality, both in my nascent gropings as a writer and in my own life choices, which I scarcely felt to be choices at all. You went to high school, then you went to college, then you got some sort of job, then… well, I could scarcely imagine what might happen after that. In fact, I could scarcely imagine having a job; I hated all the jobs of my teenage years, indignant that I was expected to exchange the hours I could have spent reading or daydreaming dishing out ice cream or ringing up groceries or stuffing envelopes, etc. Even nearly flunking out of college wasn’t quite enough to teach me that my actions (or inactions—in this case, cutting every class that didn’t interest me, which was most of them) had consequences. I can’t seem to make anything happen in the world, I reasoned, but maybe, just maybe, it was possible to skate by making things happen in my imagination.

So I became a writer. But I wasn’t the kind of writer I most admired and wanted to emulate—or so I believed after failing to slay my own personal monster in a box, the novel I scratched away at for the first half of my twenties while working for restaurants and lawyers in New Orleans. No: I wasn’t a writer at all; I was a poet. (It’s Poets & Writers, after all, not Writers, Some of Whom Happen to Write Poetry.) I wasn’t a storyteller, I told myself—I hadn’t finished my novel, couldn’t write a short story to save my life, and I’d been rejected three of the four fiction MFAs I’d applied for (I was waitlisted for one but that wasn’t sufficiently encouraging). I was what Janet Burroway calls a sensitive observer, ready to praise or damn the world but not to devise the sort of thing that attracts readers in any quantity—a plot. Plots were composed of thick, heavy strands of human relationships and social performances, phenomena I understood not at all. I was a sensitive observer—of words, and of my own confused feelings for nature and history and my dead mother, and of myself.

So I wrote what one critic has called my “spare and brittle poetry”. I spent a decade reading poetry and theory voraciously and almost exclusively, especially the gigantic unwieldy monsters of midcentury modernism—The Cantos, Louis Zukofsky’s “A”, The Maximus Poems, etc. I shunned fiction, declared all plots boring and predictable and above all untrue to life. I wrote out of a kind of embittered nostalgia for things I’d never experienced, since everything significant about my life seemed to have been determined in childhood or before I was born. Above everything else was the early death of my mother, of cancer, when she was forty-nine and I was twenty-one. My age was retrospective; I took my cue from the title of a biography of Edgar Allan Poe published the same year Mom died: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance.

So what happened next?

Plot happened. Because X, then Y…

Because of my single-minded dedication to poetry, I went to grad school, doing well enough to get a Stegner Fellowship and admission to Cornell’s PhD program in literature. Because I went to Ithaca, I met the woman who’d become my wife. Because I wanted a family, I had to get a job. Because I was lucky enough to get a job at a small liberal arts college, and because I had a kid, I gradually abandoned most of my intellectual pretensions, the load-bearing pillars of the castle in the air where I’d lived for most of my life. Because I lived with people for whom I cared deeply, I began to take better care of myself, cutting out fast food and exercising more. Because I was more in touch with my body, and with bodies in general, I took an interest in my fellow human beings and in what made them tick. Because I was a writer, I tried to write about this. Which turned me into a novelist. Which now, at very long last, is turning me into the storyteller I maybe always was.

Cause and effect. My life is not random. My life is not merely the epiphenomenon of more significant histories, but a story of its own. Imbricated, yes, in history—on today of all days I understand that. But I have made choices, and those choices have had consequences, most of them amazingly happy. I read a lot of Vonnegut and Holocaust literature when I was a kid—too much—but I also read Dickens and Tolkien and LeGuin, and experienced the magic of feeling alive in story. It has taken me much, much longer than I might have wished to feel capable of attempting such magic myself. But such was my path; such has been the plot of my life.

At the Kol Nidre service at Mishkan last night a question flashed on the screen to kick off the Amidah, the sequence of silent prayers in which for a moment you are alone in the midst of the congregation, directly addressing G-d: Who taught you to love? The question brought tears to my eyes. I thought of my father, always the more physically affectionate of my parents, who carried me on his shoulders or rubbed my head while I sat on the floor next to the couch while we watched TV. And I remembered how he’d come up to my room at the end of his long workday to sit on my bed and loosen his tie and listen, bemused and delighted, to the long and elaborate stories I told him with the aid of my toy spaceships and action figures.

It would be too simple to say that my mother, frozen by trauma, made me a poet, winning fragments of her attention with clever turns of phrase. Or to say that Dad, my first audience, less intellectual than Mom but more consistently appreciative, made me a storyteller. But it would also be kind of true.