Jack Aubrey may, as he frankly admits to Stephen Maturin early in their acquaintance, love money “passionately.” But he worships the Royal Navy, is entirely its creature, and his summit of earthly felicity is not to be rich but to “hoist his flag at last.” That is, to move off the post-captains’ list and to be promoted to the rank of rear admiral. Not just any such rank will do, however; the title of the 18th Aubrey-Maturin novel alludes to Jack’s terrible fear of being “yellowed”: that is, nominally promoted to the rank of admiral without actually having a command. A yellow admiral has been judged wanting by the Admiralty and is a figure of pity, if not of contempt. As the Napoleonic Wars drift toward their conclusion—Wellington and Waterloo leaving Aubrey little to do but man the blockade off Brest—the possibility, even the likelihood, of Aubrey’s never hoisting his flag looms large. It doesn’t help his cause that he has taken a stance against the enclosure of land in his home district, against the wishes of the admiral commanding the blockade.

Here follows an extensive digression on the Barsetshire Chronicles of Anthony Trollope: six fat Victorian novels set in the imaginary county of Barsetshire and concerned almost entirely with the doings of clergymen and their families. This is not, it becomes clear, because Trollope has any special interest in the history, let alone the theology, of the Anglican Church. It’s just that the church, as a hierarchical organization prone to faction between High and Low, is an ideal vehicle for stories of human ambition, often of the pettiest sort. Put another way, Trollope is interested in the small-p politics of the church as they play out in provincial circumstances, just as later he will write about parliamentary politics in the Palliser novels (which I have not yet read). Which curate will receive which living and who will occupy the bishop’s throne is rather more interesting to the majority of Trollope’s characters than spiritual concerns, and there’s also a great proliferation of marriage plots. Only Trollope’s eccentrics behave as though Christianity were not a mere form but the actual substance of their lives.

The Warden (1855), the first and shortest of the Barsetshire novels, will do as well as any of the rest of them to demonstrate this. The novel’s unheroic hero is Mr. Harding, the warden of a hospital with an extremely comfortable living, whose main joy in life is music—he plays, like Stephen Maturin, a ‘cello, and when nervous or upset bows an invisible instrument. A young reformer by the name of John Bold (Trollope is not above giving his characters allegorical names) goes on a crusade to argue that the money that pays Mr. Harding’s generous salary should go instead to caring for the hospital’s impoverished residents. Mr. Harding’s cause is taken up by his son-in-law, Archdeacon Grantly, whose imperious manner and thin skin belie the warmth of his heart. A wealthy, worldly man with a fierce sense of amour-propre, Grantly is a skilled bureaucratic infighter with an unshakeable belief in the inquity of those who would dare to challenge the system from which he and his benefit. He urges Mr. Harding to fight Bold—who as it happens is the fiancé of Mr. Harding’s daughter Eleanor. But fighting goes against Mr. Harding’s nature, particularly once Bold’s cause is taken up by the newspapers. He searches his conscience, and to the astonished exasperation of the archdeacon, resigns his position. Nor does he extract the petty revenge most easily available to him—to stand in the way of his daughter’s marriage. He simply yields, in Christlike self-abnegation, an action that thoroughly bewilders the numerous canons, curates, vicars, and prebendaries of Barsetshire.

Each novel repeats, with varying emphases, this contest between warm-hearted self-interest and unworldly idealism. Trollope’s genius is in the shades of gray: his saints (among them the determined old maid Lily Dale and the poor but intractable curate Josiah Crawley) madden readers as well as their friends in their obduracy, while cynics like Archdeacon Grantly are far more recognizably human in their sympathies for those they love. Though the series has its share of cads, there are no real villains, except perhaps for the indelible Mrs. Proudie, the domineering wife of the low church bishop who supplants Grantly in the second novel, Barchester Towers. Mrs. Proudie is a true believer, but in what? She rigorously and ruthlessly enforces her ideas of propriety, but that hardly qualifies her as one of Trollope’s intransigent saints—she’s more like one of the “blue-light admirals” Jack must sometimes contend with, whose intolerance of bawdy at the dinner table is a symptom of chilly authoritarianism. Mrs. Proudie is not a cynic, however: her comic menace and tragic fall stem from the purity of her identification of her self-interest with the interests of the church. There is pathos as well in Mrs. Proudie’s ascendancy over her husband; she is by temperament far better suited to be the bishop than he is, but we are mostly invited to consider that fact as monstrous. She is killed off in The Last Chronicle of Barset by the intransigence of Mr. Crawley, a lowly vicar with high moral principles, whose refusal to bend to her authority sends her into a fatal conniption.

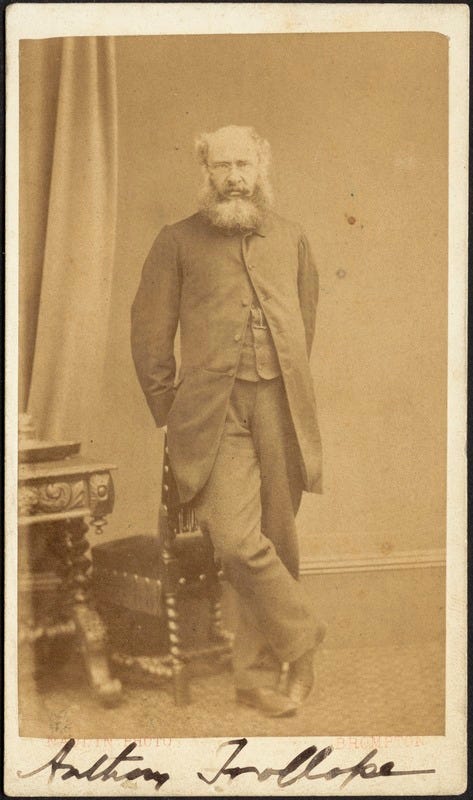

Jane Austen is the most frequently cited of Patrick O’Brian’s influences, but Trollope is almost certainly hovering in the background (in The Mauritius Command, O’Brian names one of Jack’s lieutenant after him). Like Jack, and like the clergymen who populate his Barsetshire chronicles, Trollope was an organization man who worked for the General Post Office for much of his life and who savored a good bureaucratic dust-up. He is credited with introducing the iconic pillar box to the United Kingdom. He left the Post Office in 1864 to stand unsuccessfully for Parliament, concentrating on his literary career thereafter. The forms of hierarchy—political, social, domestic—are his milieu and his subject—comedies of manners writ exceeding small, and rarely enlarged by any theological or political substance.

In a telling passage from The Commodore, Jack and Stephen discuss the career prospects of Jack’s illegitimate son Sam Panda, who has been ordained as a Catholic priest: “Jack Aubrey was as solid a Protestant as ever abjured the Pope and the Pretender, but he was deeply attached to Sam, as well he might be, and he was now as expert in the intricacies of the Catholic hierarchy as he was in the succession of admirals. He was speaking eagerly of the Prothonotaries Apostolic and their varying rows of little violet buttons when Reade came in, took off his hat, and said, ‘Tender hooked on, sir, if you please, and all is laid along,’ this last, with a significant look at Stephen, meant that Killick had carried over a small valise holding all that he thought proper for Dr Maturin to wear during this absence, and a supply of shirts.”

This passage seems to mark Jack as one of Trollope’s big-hearted cynics, whose love of the forms of hierarchy overcomes or erases his nominal contempt for Catholicism. His delight in “rows of little violet buttons” recalls his own happiness when he first affixes the epaulet of a commander to his uniform back in Master and Commander. At other times he seems to hold rank and its appurtenances more lightly; when he first puts on the admiral’s uniform he’s required to wear in The Commodore he displays himself before his family: “Behold the Queen of the May.” But Jack does fear the possibility of having the appearance of rank without its substance: a yellow admiral is an admiral with nothing to command. He would rather retire while he is still a captain than be subjected to such disgrace.

The Aubrey-Maturin novels are often read as a study of leadership. Jack is the ideal commander: decisive and wily, with a deep understanding and sympathy for ships and sailors alike. Nearly every book in the series contrasts Jack’s style of leadership with that of other commanders, the better to illustrate their failings as brutal or sclerotic, vainglorious or incompetent, as the case may be. In The Yellow Admiral he runs up as he often has against the tension between his understanding of his duty and the forms of hierarchy, earning a rebuke from the inimical Admiral Stanraer (whose nephew’s desire to enclose land was frustrated by Aubrey) when two French ships slip through the blockade while Aubrey is putting Maturin ashore for some important intelligence work. This is a minor example of the sort of trouble Jack runs into continually throughout the series, as part of an organization that, like any organization, is too often penny-wise and pound-foolish. Nothing earns quicker contempt from Jack and his crewmen than a captain whose concern for appearances—trim sails and immaculate paintwork—trumps actual preparedness for war, which for Jack is symbolized by his eagerness to exercise the great guns as frequently as his powder allowance will let him.

The same instincts that make Jack an effective commander make him a dreadful politician, both in the small-p sense of intra-naval politics and in the large-P sense (when he becomes a member of parliament). Jack’s loyalty to the Navy as such blinds him to the importance of party; he never learns the lesson that speaking up against corruption embarrasses the party in power, damaging his career and increasing the odds of his being yellowed. Archdeacon Grantly, for one, would never make such a mistake.

Of all the novels in the series this may be the least nautical; there are few significant actions at sea but plenty of doings on land. The battle against enclosure leads to a prizefight between Aubrey’s coxswain Barret Bonden and a gamekeeper in the employ of the squire who seeks to profit by turning land that supports a community of peasants into his fenced-off private property. The match ends more or less in a draw, with both combatants badly injured (its depiction appears to be closely modeled on the boxing match depicted by William Hazlitt in his wonderful essay “The Fight”), but the anti-enclosure forces are victorious thanks to Aubrey’s intervention. More seriously for our hero, Sophia’s meddling mother discovers the letters from Amanda Smith, the flighty young woman with whom Jack enjoyed an affair back in The Surgeon’s Mate, and instantly passes them on to her daughter, leading to the most serious rupture yet in the Aubreys’ marriage. Sophie is furious, but Clarissa and Diana intervene, making her understand for the first time the real importance of sex and suggesting the possibility that it’s something that Sophie might learn to enjoy—perhaps with a lover. It’s not clear whether or not Sophie takes them up on it—probably she doesn’t—but after these conversations she decides to forgive Jack. Napoleon is defeated at Waterloo, and Jack agrees to a scheme developed by Stephen and Sir Joseph Blaine to be suspended from service to the Royal Navy so that he might sail independently to Chile and aid in the independence movement there.

What is the real substance of Jack’s ambition? Is it to command in any circumstance, in any cause? Jack is no freedom fighter; if he takes up the cause of Chilean independence, it’s because it serves the interests of the British Empire to weaken the influence of Spain, and it will keep him active while other captains are thrown upon the beach. Of course history intervenes before this can happen; in the novel’s last pages we learn of Napoleon’s escape from Elba, paving the way for one last glorious campaign against the French in The Hundred Days.

Jack Aubrey has the warmth of Trollope’s cynics and the purity of his saints. He is cheerfully corrupt in causes he thinks just, seeks always to benefit and advance those closest to him, and thoroughly enjoys the good things of life without any meanness or asceticism. At the same time he is wholly identified with the Royal Navy and its mission, embodying the best of its principles of leadership and scorning those for whom seamanship is secondary to questions of rank and respect. That respect for seamanship and leadership gives him something of an egalitarian streak; he does not hesitate to promote a master’s mate to officer rank if the man in question has the skills, whether or not he can “pass for gentleman.”

And what of Stephen Maturin? If he wanted it, he could probably have risen to the rank of Physician of the Fleet, but he does not want it. Though he holds a surgeon’s warrant, he is in the Navy without being of it. As a voluntary and unpaid secret agent he is part of no hierarchy; his personal wealth makes it unnecessary for him to seek distinction in that area. He is a little like Trollope’s Doctor Thorne, a dedicated and disinterested medical man whose care is for his relations and friends rather than himself. In the novel that bears his name, his entire concern is for the well being of his niece, and to do right by his patient the roughneck drunkard, Sir Roger Scatcherd. Thorne is a melancholy being with few thoughts for his own happiness. He is, in other words, one of Trollope’s saints, utterly detached from the race for status that preoccupies his more warm-blooded characters. In a later novel Trollope marries him off to the preposterously wealthy Martha Dunstable, as a kind of reward for his saintliness, as well as a hint, perhaps, that there is more heat in the good doctor’s blood than we might have suspected. (We will recall that Stephen finds himself to be of an “ardent” temperament when he finally weans himself off opium.)

Worldiness and warmth, and the coldness of the pure heart: these tensions are at play in most of Trollope’s characters. Jack and Stephen follow similar lines, in a far different key.

P.S. As one who, though raised Catholic, spent twenty years as a pastor in a mainline American Protestant denomination, I’m also interested in your thoughts on the politics and manners of church life, and its representation in both O’Brian and Trollope! Bravo!

Thank you for sharing your thoughts on O’Brian’s work and for all the connections that you make! I take real joy in reading and rereading your posts! 🙏