Note: I first published this essay a decade ago on a now-defunct website called Press Play. Then it hung around on my blog for a while. Now that this is my blog, or blog-equivalent, I’m republishing it here, by more or less popular demand. In hindsight, this essay was the launching-pad for my ongoing investigations into representations of masculinity in popular culture and literature. Enjoy!

This is Jim Rockford. At the tone, leave your name and message. I’ll get back to you.

The party plans had been elaborate: my wife had invited all of my friends, including several from out of town who bought airplane tickets for the occasion, to surprise me at a steakhouse in Chicago’s South Loop. The party was to have an eighteenth-century “Clubb” theme, inspired by my love of James Boswell’s Life of Johnson and his journals, and by the elaborate dinners often enjoyed by Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin of the Royal Navy, as depicted in Patrick O’Brian’s series of novels. There would be costumes; there would be wigs; there would be speeches and heroic couplets and all the prime steak and good Scotch we could swallow. But: two or three days before I turned forty, I came down with a fever. The fever became severe and the glands in my neck swelled to the size of golf balls. The doctors concluded that I had a particularly virulent strain of strep throat, or maybe it was mono. I could barely speak or swallow, and the pain in my neck, shoulder, and especially my sinuses was excruciating: it felt as if a sadistic clown were inflating a giant party balloon inside my skull. The party, which was going to be a surprise party, was canceled, and Emily tearfully narrated all the details of it to me so that I could imagine it, almost taste it. Then I retreated upstairs to our bedroom, scarcely to emerge for the next two weeks, while Emily played the unfamiliar roles of nurse and single mom, and my colleagues in the English Department scrambled to cover my missed classes. The antibiotics weren’t helping and neither were fistfuls of ibuprofen. I was too dazed to read. I was forty years old. I had one comfort: my iPad, Netflix, and James Garner in The Rockford Files.

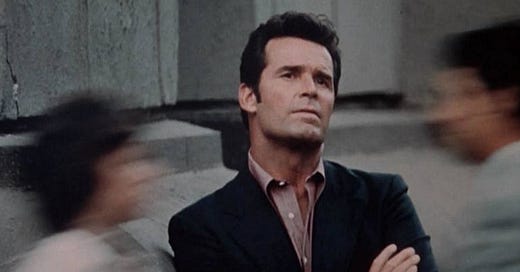

Who is Jim Rockford? The opening credits show him practicing his vocation as private eye: tailing people, asking questions on the street, arguing with cops, covering his face with an enormous bug-eyed pair of binoculars in one still. But we also see him on dates, breaking into a grin as he gets a laugh out of the woman he’s with. We see him in his trailer, cigarette on his lip, hanging up the phone, pulling a jacket on, heading purposefully out the door. We see him nonplussed in the frozen food aisle of a supermarket, recalling, at least for me, Allen Ginsberg: “In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went into the neon fruit supermarket, dreaming of your enumerations!” Ginsberg is talking about Walt Whitman, but he could just as easily be talking about the six seasons and 123 episodes of Rockford, not to mention the eight TV movies released in the 1990s. I saw you, Jim Rockford, childless, lonely old grubber, poking among the meats in the refrigerator…

But Jim’s loneliness is not as essential to his character as it is for other fictional PIs, and this is affirmed most resonantly by the last images in the credits, which show Jim fishing with his dad Rocky. Played by Noah Beery, Jr. during the show’s regular run (another actor played him in the pilot), Rocky is the show’s secret weapon, its emotional anchor, the tip of the iceberg of Rockford’s bottomless likability. Jim has a dad, and they care for and squabble with and go fishing with each other: that simple emotional fact roots Rockford’s heroics in something more human than the chilly abstract chivalry of a Philip Marlowe. It helps too that Rockford, though perennially unattached, doesn’t have a misogynistic bone in his body: here is a man who genuinely loves and appreciates women, whose body in no way shrinks or tightens in the presence of the opposite sex, who has the enviable gift of becoming larger and more like himself when he talks to a woman and makes her laugh. The Rockford Files was often a vehicle for an un-showy 70s feminism, embodied most frequently in Gretchen Corbett’s Beth Davenport. Beth is Rockford’s attorney and sometime love interest, whose mental toughness and sharp comebacks to preening judges and leering small-town cops mark her as Jim’s equal. Her sometimes brittle vulnerability makes her a good match for Rockford, who is averse to physical violence and rarely resorts to carrying the small revolver that he keeps tucked into a cookie jar in his kitchen.

There’s not much else to Rockford’s backstory: we know that he did time in prison for a robbery that he didn’t commit, that he was pardoned for the crime but maintains a network of contacts from those shady days that help and more often hinder him in his work. Most memorably there’s Stuart Margolin’s Angel: squirmy, febrile, cowardly, honest about nothing except his own brazen self-interest, the venal Pancho to Rockford’s wearily forgiving Quixote. But Jim has a never-ending series of friends from the old days always coming out of the woodwork to provide plots and motivations deeper than the two hundred bucks a day (“plus expenses”) that he routinely demands and very rarely receives from his clients. More often than not, he gets emotionally invested in his cases, and he follows them through to the end, invariably outwitting the bad guys without ever lining his wallet in the process.

Jim’s capacity for friendship is emblematic of the most enduring of the old pre-cable network shows, before HBO turned scripted television dramas into serialized nineteenth-century novels, fundamentally literary in their storytelling resources and techniques. Don’t get me wrong, I like many of those shows: The Sopranos, Deadwood, and The Wire form for me, as for many others, a profane trinity of high-quality storytelling, not least for their remarkable feel for language. And no one will ever compare The Rockford Files to Shakespeare or Dickens, as routinely happens with the three shows mentioned (though it’s worth noting that Sopranos creator David Chase cut his teeth as a scriptwriter on Rockford). But those shows’ unfolding intricacies of darkly thwarted patriarchies and institutions—the moral bleakness, the frustration of aspirations that inevitably spirals into gruesome violence—had little appeal for me during the sickness that knocked me down on my birthday. I lay in bed and watched episode after episode, becoming quietly addicted to the theme music (especially the bluesy harmonica bridge) and the square aspect ratio that fits an iPad perfectly. The Rockford Files is ghostly and homeless on a modern widescreen TV, with two black bars running down either side of it, as if parodying the horizontal letterboxed bars signifying that one is worshipping at the shrine of the dead god Cinema. That squareness extends to the show’s worldview: in spite of its veneer of post-Watergate cynicism, in spite of Jim’s willingness to bend and break the rules (most often by posing as some sort of businessman or official, usually with the help of business cards that he cranks out using a little printing press he keeps in the trunk of his iconic Pontiac Firebird), the arc of The Rockford Files bends always toward justice.

When I watch the show, I am comfortably enclosed in a decade that eerily resembles ours, with its breakdown in trust in public institutions, its vague guilty consciousness of environmental degradation, its retreat from political life into narcissism and navel-gazing. That feeling of regression is amplified by the show’s imagery, which recalls my 1970s childhood: the hairstyles, the clothes, the fragments of outdated slang, the gigantic boat-like cars that chase or are chased by Jim’s Firebird in seemingly endless, frankly boring sequences that serve now as tours of a seemingly pre-capitalist semi-urban landscape, devoid of product placement or corporate brand-names, long shots of empty sun-flooded boulevards and parking lots through which the essential dead desert of Los Angeles makes itself visible in winks and flashes. The desert of the present: sweating into pillows, the day and its business passing out of reach, my wife’s tightening face or my three-year-old daughter’s voice from downstairs asking how much longer Daddy will be sick. Steady on: here’s Jim tracking down missing girls, breaking a corrupt ring of truckers and unraveling insurance scams, and tracking down more missing girls, without ever losing his sense of humor. This isn’t the same as never losing his cool, because Jim Rockford is not cool, even in sunglasses: he lives in a trailer and drives a car the color of a polished turd and wears shapeless sportcoats and lives on tacos with extra hot sauce. Jim is warm: the character exudes compassion, cracks jokes at his own expense, bleeds when he gets punched, and has a capacity for enjoying life on and off the case that is so infectious that to me, ebbing on the bed, it felt like an almost adequate substitute for life itself.

Nostalgia encased me and buffered me from the ravages of my infection, and protected me for a while from something even more irresistible: the reality of aging. I never watched The Rockford Files when it was originally on the air: my parents only let me and my sister watch a little PBS, though when I was a little older I snuck episodes of Knight Rider and Airwolf and the Tom Baker Doctor Who whenever I could. I guess I’ve always been susceptible to stories of lone investigators and solitary knights (though they rarely lack female company). There was an odd purity to my nostalgia in watching the show, then, since nostalgia is always a longing for something fundamentally imaginary. The show had formed no part of my real experience. And yet lying there watching it through my haze of antibiotics and prescription painkillers was a real experience: there was a halo, a boundary, surrounding the washed-out colors flickering across the screen, and I was all too conscious of what that boundary was keeping out. In my vulnerable state I feared the future as I never had before: it was not just my own aging that worried me, but what seemed to be the rapid aging of the world: the ever-accelerating Rube Goldberg machine of climate change was often on my mind, and in my fever dreams I could see the desert of Jim Rockford’s Los Angeles growing and spreading and rippling outward to cover the earth. To a hallucinatory synthesized bluesy beat, the gold Firebird wove its way through the empty, sunbaked streets as if it were tracing a mandala, past poker-faced houses and burnt umber hills, a vast landscape made tiny and inconsequential. Then Jim’s face again, that grin. Action: a fist to the jaw, a hail of harmless bullets. Another case closed. Another fit of banter between Jim and his companions, his friends, of whom I was one.

That’s what a certain kind of television can do at its best: scripted series television, not reality shows or intricately plotted season-long plots or funny cat videos on YouTube. The Rockford Files, Taxi, Barney Miller: the old shows characterized by their smallness of scale, their putting plot in the service of characters or a mood. These shows weren’t Seinfeld; they weren’t “about nothing,” not exactly. They function, strangely, like poetry. In its very inconsequence, its mere being, The Rockford Files makes nothing happen:

it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

—W.H. Auden, “In Memory of W.B. Yeats”

It survives, a way of happening, in the face of James Garner in the years 1974 - 1979, a man in his forties rueful, grinning, scolding, surprised, sly, smiling. Perpetually unattached to any woman, perpetually childless, yet saved always by his relationships: with his father and with Beth and with Angel and with Sergeant Dennis Becker, the irascible but upright policeman who is Jim’s only friend on the force. Wise to the ways of the world, yet capable of being shocked: Jim’s fundamental innocence (he is, remember, that rara avis, an innocent jailbird) is the show’s hallmark: the hallmark of a decade whose pervasive cynicism is rendered moot by the simple fact of its being encased impregnably in a past that looks less fundamentally damaged, more reparable, and more fun than our present. The Seventies has become a small town, populated by familiar faces, an object of nostalgia, a homeland that never was. MeTV, indeed.

Yet Rockford’s unglamorous Los Angeles is also a raw town, and in every episode he encounters the desolate inhabitants of “ranches of isolation” with their “busy griefs.” There’s real darkness on the edges of some of the early episodes. Season One’s “Slight of Hand” presents us with a tale of Jim’s disappeared girlfriend, who vanishes from his car after a trip up the coast with the woman’s daughter, who hauntingly murmurs the phrase, “Mommy didn’t come home with us last night.” Jim solves the case but it leaves him bruised, bitter, and as close to noir as The Rockford Files ever comes. In Season Three’s “The Family Hour,” Jim and Rocky get mixed up with a twelve-year-old girl who has seemingly been abandoned by her father, played by the ubiquitous Burt Young (the sweaty cuckolded husband in Chinatown; the sweaty brother-in-law of the title character in the Rocky movies, the sweaty trucker Pig Pen in Convoy, etc., etc.). In a wrenching confrontation late in the episode, Young’s desperate father challenges a drug-dealing federal agent to kill both him and his daughter, who’s standing right there. The bad guy flinches and the day is saved, but the raw anguish on the father’s face stayed with me long after the smirky or sentimental freeze-frame that ends every episode and which, by freezing on a single image, usually of Jim’s grin, separates this universe from the universe of future episodes.

These fragments of real terror, real feeling, are hermetically sealed off from each other, and so we are shielded from the full impact of the sunlit noir that may be the decade’s most enduring contribution to pop culture. The Conversation, Night Moves, The Long Goodbye, The Parallax View, Chinatown: the great neo-noirs of the Seventies always end in the corruption, if not the outright destruction, of the hero, whose personal code proves to be no match for the systemic pervasiveness of the evil that he confronts. Jim is saved in part by not having a code: only warm responsiveness, and wisecracks, and a network of relationships that never really let him down: even Angel is reliable in his venal unreliability. But what really preserves him is the show’s illusory continuity, fundamental to the form of episodic television. There are recurring characters and very occasional references to past events, but it’s as if the show and its characters were created anew each time the credits roll. That’s the nature of nostalgia: we never play, we re-play. And I’ve seen enough episodes of The Rockford Files to feel like each new one I see is something I’ve seen before. The déjà vu is built in.

I got over my infection and got over turning forty, but I never did get over Jim Rockford. He’s still out there, somehow, waiting for the call of imaginary friendship. When you’re finished watching you may feel the chill of the twenty-first century, of real relationships rendered somehow intangible by social media or distraction or sheer carelessness. You might remember the news, or Mad Men, or the weirdness of the weather, and be impelled back toward—or father away—from what we’ve agreed to call reality. But if you’re like me you’ll also remember friendship: how fragile it is, how necessary. Nostalgia can be self-indulgent and escapist, yes. It’s also a form of friendship with the self. So the next time you’re feeling low, defenses down, the world too much with you, spend an hour with Jim Rockford. You’ll be glad you did.

I promise to get back to Patrick O’Brian eventually! Still waiting for my interview with Ian and Mike to pop up on an episode of The Lubber’s Hole. In the meantime, if you’re hungry for more Corey content, listen to the podcast interview I just did with Elias Crim to learn all about my poetry book Hannah and the Master and my novel How Long Is Now. Thanks for listening.

I never knew you connected so much to Jim Rockford. It's uncanny, because I also have intense feelings about The Rockford Files, in my early 20s, but perhaps it was identification with the actor more than the character. I remember my routine of classes in the morning, afternoon tv with the likes of the Rockford Files and junk food, then off to a shift for an evening retail job. I don't think Garner ever strays far from channeling a figure like Rockford when he's doing Maverick or his role in Support Your Local Sheriff, for example. In my own journey through masculinity awareness and oblivion, I was looking for male models of resilience and autonomy at that age. Another pole was Ian Curtis and Ernest Hemingway. Garner also happens to look a little too much like my father did in the 1970s. I intimately understood how it was possible David Bell (the protagonist of Don DeLillo's Americana) had mirrored his own imago on Burt Lancaster. Jim Rockford as imago at 40, versus 20?