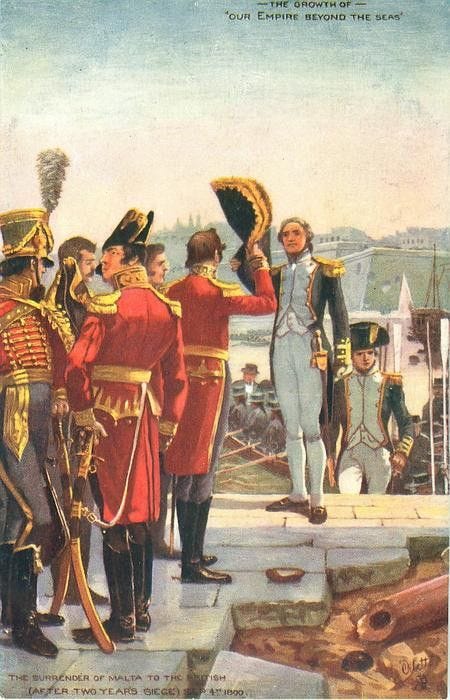

Ah, the British “U.” I’m not sure what purpose it serves, or why we Americans discarded it, so that we write armor instead of armour, labor instead of labour, and harbor instead of harbour. With or without it the title of this novel, as with others in the Aubrey-Maturin series, has more than one meaning: it refers to the treacherous harbor in which the novel’s climactic battle takes place but also to the shelter his position offers to the treasonous Andrew Wray, Acting Second Secretary of the Navy and the mortal enemy of our heroes. The geography of the literal harbor, which is indeed shaped like a U, is so important to the story’s climax that a map is provided in the novel’s very last pages—a bit of a surprise. Another surprise comes at the beginning, when the novel’s point of view, which nearly always follows faithfully either Jack’s mind or Stephen’s, strays into the perspective of the enemy agents who seek their destruction. We view, for the first time, our heroes from outside—though as O’Brian tends to think in terms of doubles and foils, our attention is called to the fact that Lesueur, the French agent, “was not unlike a somewhat older version of the Dr Maturin whose face he was now examining so attentively with a pocket spy-glass – a slight man of under the middle height, sallow, stooping, bookish, with an habitually closed, reserved expression, a man who would rarely draw attention but who having drawn it would give the impression of more than usual self-possession and intelligence.”

As for Andrew Wray, he made his first appearance back in Post Captain when Jack credibly accused him of cheating at cards; instead of calling Jack out he has been quietly working his revenge behind the scenes to deny Jack ships he’s been promised and otherwise thwarting his career at every turn. Neither Jack nor Stephen suspects this, and when they meet Wray in Treason’s Harbour, they are put off his scent by two things. First is Wray’s approval of the promotion of Jack’s extremely able first lieutenant Tom Pullings to the rank of commander—an object devoutly wished by Jack and something Wray might easily have blocked. Second is his love of music: Stephen is surprised to encounter Wray in a Catholic church listening to plainchant and weeping, so deeply moved is he by the music. (When Lesueur informs the surprised Wray that Maturin is a spy, he remarks, “He is an idealist, like you, and that is what makes him so dangerous.”) This forms a tentative connection between them, and very nearly leads to Stephen’s putting his head into the noose. The physical action of the novel—an expedition by Jack and company to Suez in search of a galley laden with treasure, and later the action in the titular harbor—is paralleled by Stephen’s navigation of the secrets and lies in Malta, which culminate in something of a replay of what he pulled off with Louisa Wogan, in which an attractive woman (in this case, the Italian wife of a Royal Navy officer being held prisoner by the French) becomes the unwitting vessel of lethal disinformation.

The two plots are intimately connected: the galley full of treasure turns out to be a trap for Jack, just as the fetching Mrs Fielding has been set as a trap for Stephen. Our heroes manage to slip their respective traps: Jack more or less consciously tests his famous luck, while Stephen’s success depends on the skill he’s developed at reading the human heart while mastering the vagaries of his own. His ability to do this—and to survive, among other things, his intense desire for a woman not his wife—is inseparable from the theoretical detachment he has developed as a physician and a naturalist. It’s the relationship between theory and practice, perception and reality, contemplation and action that produces the divide in our heroes’ characters from which the novels derive their dialogical depth.

2

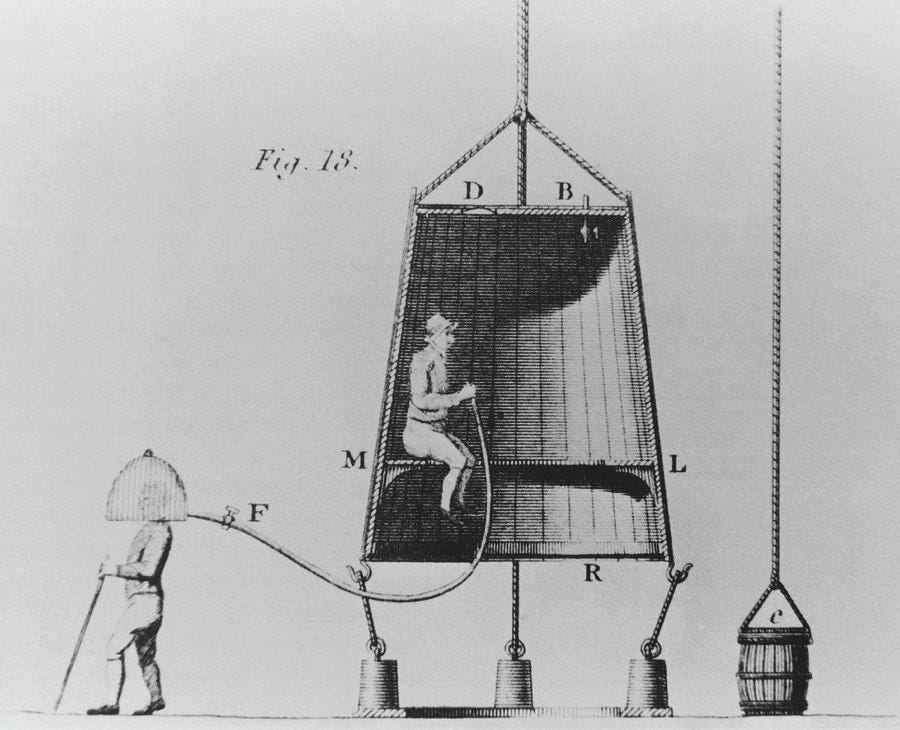

Treason’s Harbour, more than the preceding novels, is particularly concerned with the gap between appearance and reality. Our heroes’ success and survival depends upon their abilities to navigate that gap. That navigation, and the synthesis it suggests between Jack and Stephen’s fundamental orientations as man of action and man of contemplation, the man of the surface and the man of depth, has a vivid symbol in this novel: Edmond Halley’s diving bell. At first, this is played for laughs: Stephen, who lives abstemiously but has socked quite a bit of money away, has purchased the bell for scientific purposes, to walk upon the seabed and to observe the creatures of the deep through the window mounted on top. Jack, who has been put in command of a secret mission to sail to Egypt, travel overland to Suez, and then assume command of another ship to capture the aforementioned treasure-laden galley, is appalled at the thought of a massive brass bell weighing a thousand pounds on the deck of any ship he might command. It looks at first though Stephen must be disappointed of his treat:

“Two tons right over her forefoot, pressing on her narrow entry? It would make an angel gripe: it would cut two knots off her rate of sailing on a bowline. Besides, there is the mainstay, you know, and the downhauls; and how should I ever win my anchors? No, no, Doctor, I am sorry to say it will never do. I regret it; but had you spoken of it earlier, I should have advised against it directly; I should have told you at once that it would never do in a man-of-war, except perhaps in a first-rate, that might just find room for it on the skids.”

“It is Dr Halley’s model,” said Stephen in a low voice.

The unwieldy bell is a physical symbol of the disconnect that has dogged our duo since Master and Commander, when Jack promised Stephen that naval life would be sure to prove “amazingly philosophical.” And so it has been, too—but Jack’s snatching Stephen away from his investigations of this or that species or habitat in the name of of naval business, roaring “lose not a minute” as he does so, is one of the running gags of the series. Only on Desolation Island, where they were marooned for a period of weeks or months, did Stephen have the opportunity to explore and collect samples to his heart’s content. Fortunately, Jack changes his mind after he learns that the bell can be broken into its component parts and stowed down in the hold; though when Stephen expresses the faint hope that leisure might be found on their expedition to Suez to use the bell for its intended purpose, Jack dismisses this with a “Leisure, forsooth.”

Nonetheless, Stephen does find opportunities to use his bell—accompanied by his fellow naturalist, the one-eyed parson Mr. Martin, who inadvertently accompanies our heroes on their secret mission to capture a treasure-laden galley when he becomes so engrossed in looking at Stephen’s collections under hatches that he fails to notice the ship has left the dock. Its most notable usage comes after a djinn-haunted journey across the Sinai Peninsula and the sandstorm-plagued passage on Jack’s new command, the Niobe, toward the (fictional) port of Mubara. In spite of being delayed by faulty winds (and after the horrific and sudden demise of the expedition’s interpreter, a charming fellow by the name of Mr. Hairabedian, devoured by sharks while taking a dip in the Red Sea) they find the galley just where it was supposed to be. Giving chase, Jack becomes suspicious when he realizes that the galley isn’t moving as quickly as the energy of its rowers would suggest. He spots a dragsail in the water, artificially retarding the galley’s speed, and sees that the galley is leading the Niobe through a shallow channel into the Bay of Mubara, where it is likely to reach its supposed destination while the Niobe will be trapped. With the greatest reluctance—for it means foregoing the astonishing fortune the galley supposedly carries—he orders the vessel sunk. Down it goes—and the sinking is immediately followed by the booming of an unsuspected gun emplacement that would surely have sunk the Niobe had it followed the galley into the bay.

Even as Jack wonders at the situation, he must deal with the intense gloom and moral disapprobation of his men, not to mention the Turkish troops on board intended to take Mubara for the Royal Navy once the galley had been seized. It is, as Jack remarks to Stephen and Martin, “a tolerably whimsical situation, with a crew of paupers floating over a fortune, knowing it to be there, seeing its coffer as you might say, and yet unable to reach it.” Then Stephen pipes up with the sort of scatological double entendre of which O’Brian is so very fond:

Killick brought the coffee-pot, setting it down with a sniff; and after a short silence Stephen said ‘I am an urinator.’

‘Really, Stephen,’ exclaimed Jack, who had a great respect for the cloth. ‘Recollect yourself.’

‘It is well known that I am an urinator,’ said Stephen, looking at him firmly, ‘and in recent hours I have felt a great moral pressure on me to dive.’ It was quite true: no one had openly suggested anything of the kind, and after Hairabedian’s fate no one could decently even hint at it, but he had observed many low-voiced conferences, and he had intercepted many glances directed at his diving-bell, now stowed upon the booms – glances as eloquent as those of a dog. ‘So with your permission I propose descending as soon as John Cooper shall have reassembled the bell. My plan is to attach hooks to the openings in the galley’s deck, which being hauled upon will break up the floor-boards, revealing all that lies below.

Stephen, of course, uses the word urinator with perfect accuracy, and his offer is gratefully received by the entire ship’s company. Yet when he and Martin succeed in their dive, and break into the galley, and bring aboard one of the heavy boxes supposedly laden with silver, an unpleasant discovery is made upon its opening:

The expectant, happy faces, even more crowded now, looked taken aback, puzzled. The more literate slowly read Merde à celui qui le lit painted in white upon a dull grey block of metal.

‘What does this mean, Doctor?’ asked Jack.

‘Roughly whoever reads this is a fool.’

A tool of scientific discovery—of the disinterested contemplation of nature and its creations—proves instrumental in discovering the true extensive nature of the trap into which Jack and Stephen were led. The late Mr. Hairabedian, though amiable, was Wray’s man—Stephen discovers the diamond chelengk gifted to Jack as a reward for the success of The Ionian Mission, thought lost, hidden among Hairabedian’s effects. The extent of the conspiracy becomes more apparent as the book goes on, climaxing in another trap set by Wray, designed not only to bring about the destruction of Jack, Stephen, and the Surprise but of his own father-in-law, the egregious but very wealthy Admiral Harte, to whose daughter Wray is married and through whom he will inherit a fortune.

3

The phrase “the bifurcation of nature” comes from Alfred North Whitehead’s 1920 book The Concept of Nature, one of the first fruits of this mathematician turned philosopher’s heroic effort to assimilate the implications of Einsteinian relativity and the new quantum physics for philosophy. He writes:

What I am essentially protesting against is the bifurcation of nature into two systems of reality, which, in so far as they are real, are real in different senses. One reality would be the entities such as electrons which are the study of speculative physics. This would be the reality which is there for knowledge; although on this theory it is never known. For what is known is the other sort of reality, which is the byplay of the mind. Thus there would be two natures, one is the conjecture and the other is the dream.

The bifurcation of nature breaks the world into two incompatible realities, or rather two locations vis-a-vis a fundamental reality inaccessible, in Whitehead’s formulation, save by means of the human mind. This intolerable situation will lead him to develop the process philosophy for which he is best known, as developed in his masterwork Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. But I am more interested in the division of epistemologies suggested here between those who construct theoretical models of the world and those who live in in the “dream” of “apparent nature.” As Whitehead puts it:

The nature which is the fact apprehended in awareness holds within it the greenness of the trees, the song of the birds, the warmth of the sun, the hardness of the chairs, and the feel of the velvet. The nature which is the cause of awareness is the conjectured system of molecules and electrons which so affects the mind as to produce the awareness of apparent nature. The meeting point of these two natures is the mind, the causal nature being influent and the apparent nature being effluent.

Whitehead here anticipates “the two cultures” of C.P. Snow, who in his famous 1950 lecture warned of the division of our intellectual life into two groups mutually incomprehensible to one another: “literary intellectuals” on the one hand—concerned, it may be, with “nature apprehended in awareness”—and physical scientists, preoccupied with “the nature which is the cause of awareness” on the other. This echoes, at least to my mind, the romantic division of temperaments described by Friedrich Schiller in his essay “On Naive and Sentimental Poetry,” first published in 1795 and something Stephen or Professor Graham might well have read. For Schiller, plants, animals, and other natural objects “are what we once were; they are what we ought to become once more.” The naive way of thinking belongs to children and the childlike; the naive poet “moves us through nature, through sensuous truth, through living presence” whereas the sentimental poet “moves us through ideas.”

It seems to me that the two cultures, and the two modes of apprehending nature, are very much at play in the relation between Jack and Stephen; though neither is a pure representative of one or the other, it is the interaction of their perspectives that make them so successful, causally (in terms of narrative construction) and apparently (in terms of readerly pleasure). At the same time, our delight in their characters derives from a quality of naivete that both possess in surprising abundance.

On the most basic level we might identify Jack with the apparent and intuitive relation to the world and Stephen with the causal and speculative one. The division breaks down if we push it too hard—Jack, after all, is devoted to the higher mathematics, as speculative a realm as one might wish, while Stephen’s aesthetic appreciation of the birds and other wildlife he studies is his intensest and most reliable source of happiness. Nevertheless, the distinction holds, even when the exception proves the rule: Stephen the man of science versus Jack the man of action; Stephen the “inhuman” medical man versus Jack the jolly tar; Stephen, who sometimes raises an eyebrow at what he sees as the Royal Navy’s ingenuous respect for literature, and Jack, incredulous at Stephen’s inability to retain even the most basic understanding of the tides.

Each, on his own ground, is moved and amused by the permanent naivete of the other. Jack is childlike in his delight in sailing, in a good blow, his love of horses; he is easily bamboozled and manipulated by women and cunning landsmen. Stephen is childlike in his love of birds, in his indifference to cleanliness, and in his complete inability to distinguish starboard from larboard.

In the early nineteenth century of which O’Brian writes, the bifurcation of nature was still in its infancy. It was still just possible for a character such as Stephen Maturin to know everything—to have a complete world-picture in his head, as granular in his understanding about human anatomy or the life cycle of the Rodriguez solitaire as he is about Catalan politics or Latin poetry. Jack is not so knowledgeable, but he floats serenely (sometimes maddeningly so) upon the naval and cultural traditions that he takes for granted—“the immemorial custom of the service” is his infallible guide to the future and past. Modernity and revolution scarcely touch Jack, save as opportunities to practice his profession. Stephen, as the scion of two colonized nations, is a little less inclined to take his world for granted, but by the time we meet him in Master and Commander he has already put aside his millenarian hopes. Not long after, he makes the pragmatic choice to serve the imperial British state as the lesser of two evils.

4

I have been sitting on this essay for many weeks. The term ended, and I taught Shakespeare for a month; I had COVID for the second time and had to get over that; and like so many other people I’ve been reeling this week from the actions of a rogue Supreme Court that seems intent on dismantling utterly the freedoms and advances in democratic equality that I, born in 1970 (the year the first Aubrey-Maturin novel was published), once took for granted. The world breaks in on the reader, as it has done before, and I can no longer regard, for example, Stephen’s refusal to consider assisting Diana with an abortion in The Surgeon’s Mate with equanimity. I am besieged with a peculiar mixture of helplessness and hubris, wondering if I shouldn’t, in my reading as well as in my writing, not be attending entirely and with every nerve to the present crisis, rather than loitering in the early nineteenth century.

Yet I find I must be unfaithful, at least at times, to the mind-flattening urgencies of the present, expressed as they are by a social media feed that demands that we react without reflection or real conversation to the atrocity of the moment. I must step outside my own time, my own concerns, into the space of imagination, which at a minimum makes life worth living and at a maximum becomes the crucible for alternative ways of seeing, thinking, and acting. So I will go on with my reading and writing, adjusting as always to the pressures of the present. I am more attentive now, for instance, to the status of women in O’Brian’s world, and the means they find to resist or subvert the patriarchy that insists they are property. The arbitrary actions of judges and lawyers shine in a more sinister light. And I take note of O’Brian’s double-edged depiction of romantic idealism—the dream that puts the shine on a storm for Jack or a petrel’s wings for Stephen, but that for the likes of Andrew Wray becomes a justification for treason and murder.

I return to Jack and Stephen and the joyful Surprise for the little world they build together, cramped and oppressive and all-male as it may be, because there is a kind of bliss in parenthesis. In a different context I have written about the value of stepping outside the present tense for a while, transcending through poetry the deadlocks of social and political life for the purpose of returning to that life with a new perspective. Jack and Stephen’s wooden world is very far from perfect, but to visit it is a refreshment and a stimulant. We need such refreshment more than ever, to return to the world we are making as a world we make, and which we might make differently if we so choose.

At the end of Treason’s Harbour, as I said above, Jack and Stephen escape the traps set for them by Lesueur and Wray, by a combination of cunning and luck. Each in this case proves capable of looking beneath the surface of things—neither, at the crucial moment, is caught in his place of naivete. (When they are so caught, for the most part, it is played for comedy: Jack is hoodwinked by a landshark, Stephen takes an unscheduled dip in the sea.) Together, they represent nature unbifurcated, theory united with practice. A good set of friends to have in dark times.

Friends, I will remind you that I have published some books recently. If you like what I do here, you will enjoy reading what I do there. And if you could find it in your heart to give either or both of my newest volumes a positive review on Goodreads or Amazon, please do!

Joshua Corey writes an impeccable prose that resonates with echoes from the past, even as these echoes propel his narrative onward in the present and beyond, into the future. But that is not all. This is the Portrait of the Artist as a Jewish American male in the early years of the 21st century. His characters hail from a kind of ideal America where people read books and esteem a good education, which in no way absolves them of the tragic rhythms of action that surround their lives. This is the first contemporary novel that I've read in which I have gone back and re-read a paragraph—because it was so good—and not once but several times.

—M.G. Stephens, author of Kid Coole

“Who may reach into the depths of terror, but lovers?” asks the MASTER in Joshua Corey’s spellbinding new collection. The question unfolds and folds back on itself multiplying in breathtaking, visionary waves. In this erudite and unflinching landscape, the characters (Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger, Simone Weil, to name a few) exist both at the margins and at dead center of the 20th century’s furious catastrophes. Being and non-being, poetry and philosophy, fiction and nonfiction, prayer and play, crash into each other creating luminous shards of history, desire, and heartache. Structured like an epic riddle, this book is the perfect mirror in which to discern the resurgence of fascism today.

— Sandra Simonds, author of Triptych