Bartleby Boys

The only winning move is not to play

“I am a rather elderly man.”

The first sentence of Herman Melville’s story “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street” seems bland on first inspection, without any of the audacious Old Testament savor of “Call me Ishmael,” the most famous first sentence in all of literature. It’s a very basic sentence. “Call me Ishmael” calls out the reader, and calls out the narrator’s otherness; “I am a rather elderly man” hinges on the anodyne words rather, elderly, and maybe most significantly, man. But like “Call me Ishmael,” the first sentence of “Bartleby” reads as a plea for understanding, if not identification. I’m just a tired old man, this narrator insists, who found himself in a situation rather above his head—who in a sense, like Ishmael, ends the story he has to tell clinging to a coffin.

This lawyer-narrator is not a bad guy; his responses to Bartleby’s famous intransigence (“I would prefer not to”) are invariably humane and reasonable, or at least rational. Though he abandons Bartleby repeatedly, he seems to understand on some atavistic level that he and Bartleby are bound together, that he has some kind of ineluctable responsibility for the welfare of his palely loitering clerk.1 When Bartleby dies after being jailed, having preferred not to eat, the narrator learns that Bartleby had been previously employed by the Dead Letter Office of the Post Office in Washington: “Dead letters! does it not sound like dead men?” You can read the story as a Christian parable: the lawyer adheres to the letter of the law, but not its spirit, and is unable to recognize Bartleby as a Christ figure until he has made the ultimate sacrifice. “Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!” The famous last sentences of the story hint to the alert reader that Bartleby is the Son of Man.

This is a story about men. The narrator is “a rather elderly man” and every character in the story is male. Bartleby has male coworkers, two fellow scriveners and an office boy, working together in rather machine-like fashion in a dismal Wall Street office copying legal documents. (Crucially, the narrator is the only writer in the story; the other characters have the dreary task of copying what he writes.) The narrator has no name; his employees, other than Bartleby, get by with nicknames. Turkey is “a short, pursy Englishman of about my own age, that is, somewhere not far from sixty,” and an alcoholic. He’s a good worker in the mornings, but after lunch, when his face “blaze[s] like a grate full of Christmas coals,” he becomes “reckless,” “noisy,” and “indecorous.” His opposite number, Nippers, is “a rather piratical-looking young man of about five and twenty” whom, in the narrator’s view, is “the victim of two evil powers—ambition and indigestion.” Nippers has ill-defined political ambitions, and is forever struggling to correct the height and angle of his copying table; he is as useless in the morning as Turkey is in the afternoon, and vice-versa. The office boy, Ginger Nut, is “a lad some twelve years old” whose father, a trolley driver, hopes to turn his son into a lawyer; he is named for the spicy biscuits that the men in the office seem to live on, as well as the “Spitzenbergs”—a kind of apple—of which Ginger Nut is the purveyor.

Turkey and Nippers are caricatures of the soul of man under capitalism, and they present two variations on toxic masculinity. Both men seethe with barely suppressed ressentiment, as signified by Nippers’ violent but futile battle with the means of (re)production (his drafting table) and the grating, passive-aggressive catchphrase—“With submission, sir”—with which Turkey sprinkles his every utterance. In spite of the many “blots” he produces on his inebriated afternoons, Turkey clings to his position in the lawyer’s office, substituting obsequiousness for competence. Nippers, meanwhile, is “piratical”: he is ambitious, but not in an above-board way. Grinding his teeth, hissing maledictions, holding meetings with “certain ambiguous-looking fellows in seedy coats”; Nippers aspires, but he does not act. They are the ideal employees for a man who declares:

I am one of those unambitious lawyers who never addresses a jury, or in any way draws down public applause; but in the cool tranquility of a snug retreat, do a snug business among rich men’s bonds and mortgages and title-deeds. All who know me, consider me an eminently safe man.

These men produce nothing, neither do they act to anyone’s benefit but the firm’s bottom line. They’re hardly modern finance bros, but they are certainly parasitical (if not piratical) on the real economic and political life of the nation. (Bartleby’s former position, in Washington, was lost after “a change in the administration”; for him we must make the careful distinction between a parasite and a slacker.) There is something distinctively damaged, even incel-like about these characters. Turkey self-medicates with the bottle; Nippers is a “sour and sulky” man who “knew not what he wanted,” afflicted by “irritability and consequent nervousness,” who fantasizes about offering physical violence to Bartleby. For the most part the story’s characters do everything they can to avoid decisive action. The narrator’s solution to Bartleby’s haunting his office is to sneak away and relocate without telling him. When he fails to persuade Bartleby to leave the empty building and come live with him, he flees the scene in his carriage (his strangely cradle-like “rockaway”), where he virtually lives for the period of time required for the dirty deed to be done. His former landlord reports Bartleby to the police, who drag him to the Tombs on a vagrancy charge. There Bartleby withers away, a scrap of humanity whose only existence persists in the narrator’s conscience, and in the story in our hands.

Bartleby disturbs us by manifesting the exploitation on which raw capitalism depends up from the factory floor into the sanitized space of the modern office. I think of another Melville story, “The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids,” which contrasts the “paradise” of an all-male troop of lawyers and writers enjoying a bountiful dinner with the hellish working conditions of young New England women laboring in a paper factory. To dominate and exploit is to be coded masculine; to be dominated and exploited is to be coded feminine (something similar goes on in the all-male world of the Pequod, and in the various vessels Jack Aubrey commands). Bartleby, “the pale, poor, passive, mortal” is a more feminine figure than Turkey or Nippers. But Turkey is a superannuated alcoholic and Nippers, though “piratical,” is very from being a pirate. To return to that opening sentence, the modifying phrase rather elderly reads as the inverse of of sound mind and body. The whole story is a kind of special pleading by an old man who feels himself in the wrong, though everything surrounding him in his society tells him he is right.

I would prefer not to. Bartleby’s strange word “prefer” infects the narrator and the other characters; infects the story; infects the reader’s mind. To prefer is not to revolt, or even to choose. It is a kernel of the will. If Nietzsche’s ressentiment is the revenge of the weak, Bartleby’s prefer is something more humane. It is something more like the protest of a disabled person asking society to acknowledge that he is being asked to function in a world not made for their needs.

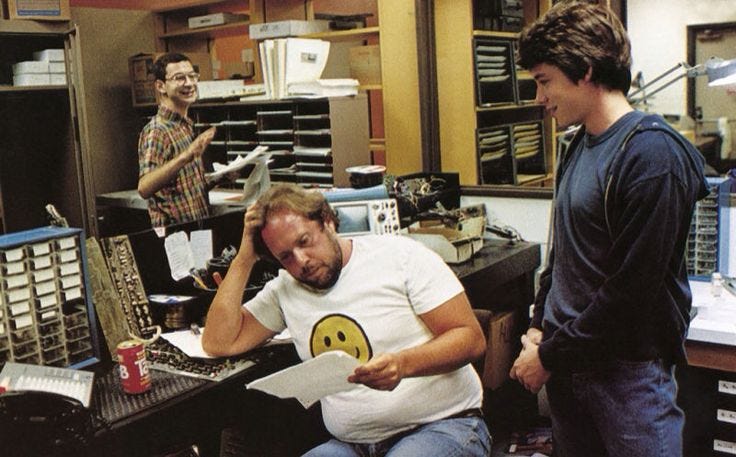

When I was twelve years old I saw the movie WarGames (1983), starring Matthew Broderick, who was already 21 or 22 but was quite convincing as a teenage computer nerd who inadvertantly hacks his way into NORAD and very nearly starts World War III. Broderick’s character David was all too easy for me to identify with as a socially awkward kid obsessed with computers and with games, who ends up living beyond his most grandiose fantasies as he first endangers and then saves the world (and gets to kiss Ally Sheedy while he’s at it). The movie gets a lot of comic mileage contrasting Broderick’s snotty-nosed kid with the serious-looking men he encounters under Cheyenne Mountain: Dabney Coleman’s McKittrick, Barry Corbin’s General Berenger. The film also offered a fairly early depiction of AI. While not nearly as charismatic as one-eyed Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey, the sentient computer WOPR (War Operations Planned Response) achieves a certain pathos from its eagerness to play games with what it imagines to be its “father,” John Wood’s Dr. Stephen Falken. That Falken nicknames the machine “Joshua,” after his dead son, aroused a certain confused identification in me, as though the computer and the Broderick character were two aspects of the same person.

Spoilers ahead. At the film’s climax, Joshua has gained control of the military’s nuclear warheads and is about to launch them so as to win the “game” it thinks it’s playing with David. David persuades it to play a series of simulations against itself; each follows the logic of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD). After a nightmarish series of simulated nuclear wars on NORAD’s multiple giant screens, the screens go dark, and Joshua issues his conclusion in his froggy computer voice: A STRANGE GAME. THE ONLY WINNING MOVE IS NOT TO PLAY. The lights go up. The world is saved.

That’s how I felt for many years about being a boy, about masculinity. My only place in the feral hierarchy of boyhood was at the bottom, so I more or less consciously opted out. Play (or talk about) football, baseball, basketball, or any other sort of ball? Boast about (nonexistent) sexual conquests? Pretend that I didn’t read books, only speak in monosyllables, swim in homophobia? I WOULD PREFER NOT TO.

Maybe that’s too slender a thread on which to hang a connection between a 1983 Matthew Broderick vehicle and a classic of nineteenth-century American literature, but I don’t think so. Broderick’s David Lightman, like Bartleby, is a slacker, an outsider, whose only friends prior to meeting Ally Sheedy’s Jennifer are a couple of computer nerds played by Maury Chaykin and Eddie Deezen read today as neurodivergent. David’s pale, unathletic body and social awkwardness are signifiers of a vulnerability that might inspire protectiveness from a woman like Jennifer but invites violence from men, who need scapegoats to distract from their own vulnerability. David refuses to play the game of toxic masculinity, but gets pulled through a “back door” into the ultimate macho stand-off, the final battle of the Cold War. He saves humanity by teaching the machine to prefer not to.

Maybe we can save our own humanity the same way.

I am reminded of the many sailors Jack Aubrey rescues from drowning, and the strangely permanent relationship this creates, as signaled in this passage from The Ionian Mission: “Captain Aubrey, a powerful swimmer, had had the misfortune to rescue Davis from the sea, perhaps from sharks, certainly from drowning, many years before. Davis had at no time expressed any particular gratitude, but the fact of the rescue had given him a kind of lien upon his rescuer. Having rescued him, Jack was obliged to provide for him: this seemed to be tacitly admitted by all hands and even Jack felt that there was some obscure justice in the claim.