[Author’s note: This may be the last installment for a while. My duties as editor-in-chief of The Fortnightly Review are taking up more of my time, plus I’m trying to finish my Jack Ruby novel. I’ve learned a lot from this experiment in serializing an unpublished novel, including some things that are making it a better story. But I’m also learning that Substack may not be the right medium for such a project. It’s been nice to know that there are some readers for the book, and I deeply appreciate everyone who’s read a chapter or paused to hit the “like” button. But are “likes” what a novelist should be pursuing? My real goal is to publish the novel in book form—that’s the best way to read it—and I will only continue to publish it here if I think doing so serves that goal. At the moment, I’m not so sure. I am certainly interested in reader feedback, so do go ahead and comment or drop me an email if you have thoughts.—JC]

Once again Lila was not in class, and he began to wonder if he should seek her out. He pictured himself knocking upon the First Founder’s front door: who would answer? With Lila on his mind, he was nonetheless startled to find her waiting after class, outside the door of the office in which he sometimes sat grading papers or staring out the window or sleeping, curled uncomfortably on the loveseat across from his desk. He took a deep breath when he saw her, tried to smile. “Are you here to talk about the final exam?” he said, a little too loudly, as a pair of his colleagues swept past.

Lila looked into his face. “That’s right.”

They went into the office together and he closed the door behind them and locked it. She sat on the loveseat. He dithered for a moment before taking a seat on the edge of his desk. Outside through the window the wind of their now northerly latitude tempest-tossed the trees.

“I saw Dr. Jee this morning,” he said abruptly. She looked at her fingernails. “He says you’re doing well.”

She looked up at him sardonically. “Aren’t you going to congratulate me? Knocked up at seventeen.”

He managed to smile. “This is a good thing,” he said, as if trying to convince himself. “Good for you, good for Concord. Have you told your father yet?” She shook her head, hair swinging to hide her face. “Don’t you think you ought to?”

“I don’t have a father,” she said softly.

“You know that isn’t true.”

“Have you met Marco?” she said, deadpan. “He’s First Founder, sure. That doesn’t make hiim dad material.” The sardonic smile. “They fuck you up, your mum and dad,” she quoted. “Maybe I’m lucky not to have them.”

Saul stood up in his agitation, turned to the window. “It must have been difficult for you to grow up without a mother.”

“We all do that.” She went back to examining her fingernails, which were painted a delicate shade of pink and immaculately manicured, all except for the left index which was ragged to the quick, as though she could not stop herself from nibbling on it. She scratched her arm, then stopped when she saw him looking. “We have Mother Dorian,” she said.

Claudia Dorian, the Crèche Mother, was a compact, efficient, imperious woman who seemed naturally of the same mouse-gray color as the uniforms her subordinate Sisters all wore. She was not often sighted outside the Crèche dome, though the Articles of Association required that she meet both Commodore and Constable on a regular basis. Only once had Saul seen her put aside her prim façade, laughing at the Commodore’s bawdy jokes as they sat across from each other at a table in the village’s fine-dining restaurant, projected to be French at the time—La Micheline. When Mother Dorian fixed you with her glittering eye you could actually see her adjusting her internal thermometer from cool to icy to subzero, depending on her interlocutor’s status. Anxious parents hoping to bear some influence on their children’s futures—Vital Services eligibility was decided after a series of physical and mental tests, usually before the subjects had turned twelve—were met with a steely simulation of warmth, a crinkling at the corner of the eyes, that agitated and soothed them by turns. Leaving, of course, with nothing but the assurance that their child would continue to experience excellent care without them until they turned eleven, these parents would feel themselves to have been further unwound, further unraveled, more dependent than ever on Mother Dorian’s small mercies. At La Micheline she had traded dishes with the Commodore while two of her Sisters watched over her from a nearby table, their faces hidden behind their customary masks. Saul had wondered what they must have thought of Mother Dorian’s performance as she laughed and flirted with the old man. At the evening’s end she’d marched out of the restaurant with a Sister on either arm, her own mask restored, offering scarcely a nod to the table where Saul had been dining alone. That bare civility told him all he needed to know about where he stood in the hierarchy of Concord as Dorian understood it. His status as Second Founder cut no ice with her, and he could not blame her for that. It certainly cut very little ice with himself. But to Lila, she was the only mother she’d ever known.

Now Lila was speaking: “I saw her yesterday, you know.”

Saul tried to conceal how uneasy this statement made him feel. “Where?”

Lila, chewing her fingernail, didn’t answer.

“What did you talk about?”

She shrugged. “School. David, a little bit.”

“David,” he said stupidly.

She just looked at him. “Oh,” he said. He remembered suddenly how distracted David had seemed in class, how he’d been unable to stop staring at Lila’s empty desk. Saul rubbed his temples. “You didn’t tell her about the baby?”

“I’m not stupid,” Lila snapped.

“Of course not.”

“I just wanted to see her, that’s all,” Lila said. “It’s a pain for her to come outside—she has to decontaminate on both sides—but I knew she’d come to me if I asked. We went for walk by the Pond. I can’t remember the last time I saw her outside, but she looks exactly the same. I mean, she covers her hair, so it’s hard to tell, but her face hasn’t changed. I remember that face. In some ways I know that face better than I know Marco’s.”

Saul nodded. Her refusal to call Marco Father or Dad made his heart lift a little, though he could not have said why.

“She isn’t a nice person,” Lila said. “I know she’s not. But she was there, you know? She’s always there. She isn’t sweet or kind but she took care of me. Of all of us.”

Saul looked out the window into the oncoming dusk.

She twisted her hair in her hands. “She’s the first person I remember. Not... not my real mom, not Marco, not any of the others. Not you. When I was very little, not much more than a baby, I remember how she came to my bed every night, to give me my medicine. Maybe not every night but it felt that way. She said it was supposed to protect against infection but I think it was to help me sleep. To stop me thinking. Do you think a lot when you’re trying to sleep?”

“Sometimes.”

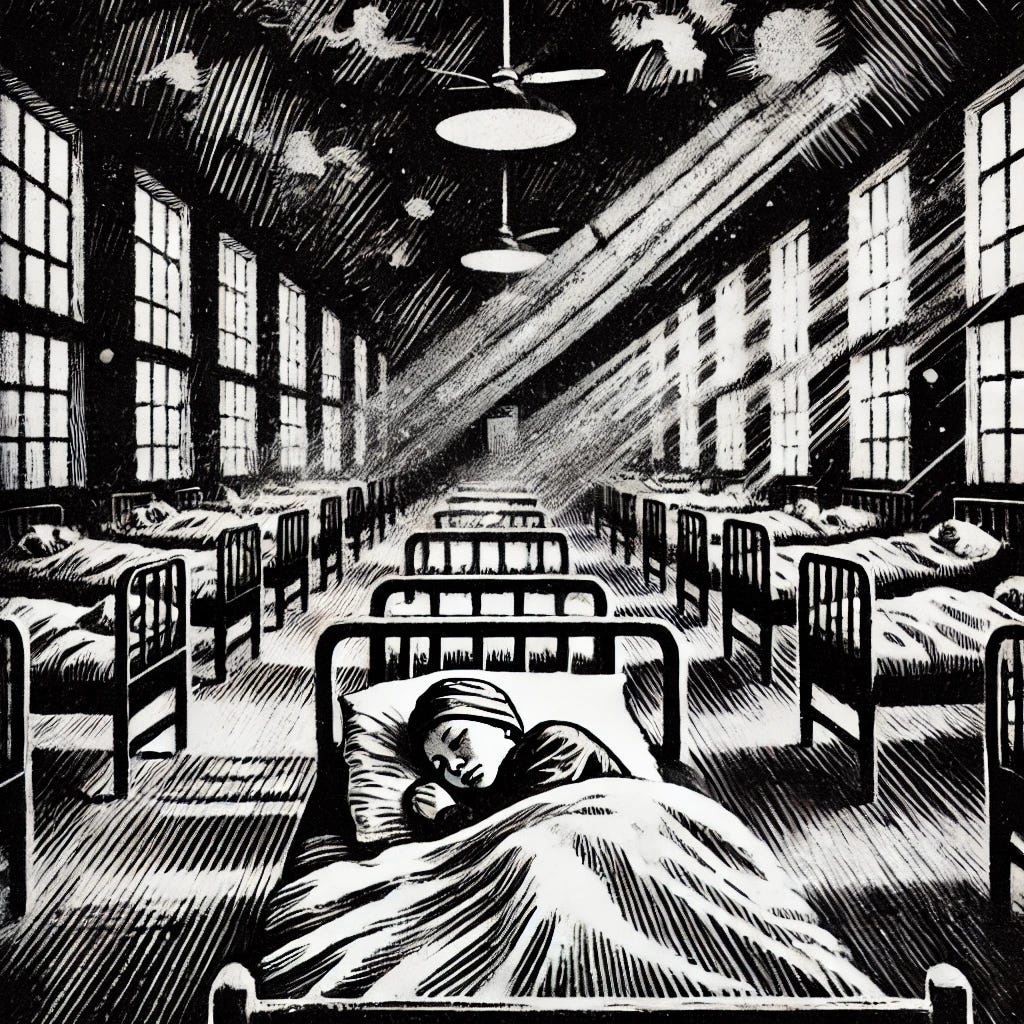

“What I remember is being in bed in the ward with the other girls, and they were always asleep already. No one else had trouble sleeping, just me. Little sleeping hills, that’s what I thought they looked like. Like the snow in pictures. I would lie there, waiting for her, for what felt like hours, totally still. All I could do is clench my leg muscles and relax them, over and over again. And there were pictures in my head I can’t describe. They weren’t even pictures. Just lights with monsters in them.”

Her voice was toneless. He noticed he was holding his breath and exhaled as quietly as he could.

“Sometimes I’d fall asleep like that, rigid and flat as a board. But on the other nights it was always the same—snapping awake, as though I had fallen asleep without noticing it, like I had finally relaxed. And I’d open my eyes wide, and there she’d be.”

The room rang with migraine light. He forced his fists to relax.

“I was saddest when she was there,” Lila said. “Not scared, sad. Because I was glad that she had come, that I wasn’t alone. But in another moment I knew I would be. And there would be dreams.”

“What did you dream about?”

She started, as though she had forgotten he was listening. “It’s stupid.”

“Tell me.”

“It wasn’t even really a dream. It’s just that sometimes, I’d open my eyes, and instead of Dorian, I’d see her. My real mom.”

The name hung unspoken between them: Suzanne. Saul held himself still, the way one tries not to spook an animal stumbled upon in the forest.

“I’ve seen pictures,” she said. “They’re not hanging up anywhere but Papa used to let me play with an old tablet, and there were pictures on it. Of her, and me as a little baby.” She gave him an appraising look. “There are even a few pictures of you. Anyway. I know what she looked like. I saw her in my dreams.”

“Did she say anything?”

Lila shook her head, smiling slightly, as though he were the child. “They’re just dreams.” She looked at him. “You know what she was really like. You tell me what she said.”

“She loved you very much,” he said hoarsely.

“On the tablet there was a little video of the two of you together. It looks like you’re in some kind of, I don’t know, magical castle. Except you’re really in a boat, but there are stone walls on either side. It’s like a moat. Were the two of you in a moat?”

“I doubt it.”

“You’re lying down,” she said slowly. “Together in this boat. A man in funny clothes is pushing you along with a stick. You look happy. You’re looking at each other. My mother is smiling and you look like this.” She raised an eyebrow coyly and puckered out her lips.

“Really?”

“Not really,” she said, relenting. “The angle is weird and I can mostly just see the back of your head. But I knew it was you.”

“Venice,” he said. “In Italy. A city built on water. It was one of the first places to vanish. It had been vanishing for years.”

“Your inspiration, right?” She frowned. “I wish Concord would vanish. Maybe if you turned those stupid projectors off for a start.” The frown deepend. “Italy, where Marco is from. That makes me Italian, right?”

“Half.”

She shook her head. “Florence, Venice, Italy, Europe. They’re just names. Like words for animals that don’t exist anymore. They’re not alive.” She looked up at him. “You’ve probably never been inside the Crèche, have you?”

“Not since before the launch, no.”

“I know there’s projectors everywhere to make Concord look like… whatever it’s supposed to look like. But in the Crèche they’re everywhere. They used to project pets for us, cats and dogs and hamsters, and teddy bears and dragons and anything else you can think of. You can see them, you can even pet them, sort of. But they aren’t real, because they can’t die.”

He held his breath picturing her, a child in the white wards of the Crèche, stretching out a half-sleeping hand to caress the fur of a passing dog, touching only air.

She frowned. “You tell us lots of stories, Mr. Klein. So does Mother Dorian, my father, everyone. But none of it seems any more real than Shakespeare, or Greek mythology. Just stories. How do we know if any of it really happened?”

He smiled. “You’ll just have to take our word for it.”

“Your word?”

“Sometimes stories are all we have.”

She looked at him steadily. “Do you know any stories about my mother?”

The pain was behind his eyes and a different pain was in his chest. He wiped his eyes.

“You loved her,” she said. “Didn’t you.”

“Yes.” It relieved him to say it. The thickness in his throat relaxed, though the migraine aura was stronger than ever.

“That video,” she said after a pause. “Where did Marco get it? Did he know?”

“I don’t know,” Saul said, thinking about Suzanne’s weight against him, the rhythm of the gondola, the stroke of the oar. “Working somewhere.”

“Working.” She said the word with distaste. “The great Marco Vespucci, always working on behalf of the Concord Ideal, right? You know what he does? You know what he’s doing in that room he calls an office, all day long?”

It isn’t right, Saul said to himself. It isn’t right that someone so young should be so bitter. So bitter and so sure. “No,” he said aloud.”

“Solitaire,” she said. She laughed. Saul laughed too, a little. “Whenever I go into his office, he’s playing solitaire, all by himself. He just plays solitaire on his computer, for hours.”

“He used to do that when he was coming up with his best ideas,” Saul said. “You can never count Marco’s mind out.”

“What was he working on?”

His gesture encompassed Concord. “This.”

“Yeah, well. Look how that turned out.” She attacked her ragged fingernail. He heard her mumble, “It isn’t fair.”

Saul wondered what she meant. Not fair that he had loved her mother? That he had ridden in a gondola with her, and that the man she’d been told was her father knew about it? That it was Saul who had truly touched her, made loved to her, heard her whisper his name?

“No,” he said. “It’s not.”

Lila gathered her things. “I should go.” She stood and looked at him. “I’m going to see Dr. Jee. At his house, not the clinic, so Nurse Bruce won’t know.”

“What are you going to tell him?”

“That I don’t want this.” Her sweeping gesture imitated his. “Any of it.”

“Lila, wait.” He searched for what to say. “Does David know?” he asked lamely.

Her eyes were hard. “What difference does it make?”

“He’s the father, isn’t he?”

She shook her head, but it wasn’t a denial. He touched her lightly

on the shoulder. “Talk to Dr. Jee. That’s a good idea. But don’t do anything. Not yet.”

“Why not?” She shook his hand off. “What business is it of yours?”

“David’s a good kid,” he said. “A good man.” He took a breath. “He’ll be a good father to your child.”

“I don’t want this,” she said again. Then she shocked him by standing on tiptoe to kiss him dryly on the cheek. “Thanks for trying.”

For a long time after she’d gone he stood at the window, one hand to his face where her lips had touched him, watching the treeline.

The wind raked its iron comb through the pinetops, bending them as one to its will.

I've read every installment but I don't always remember to hit "like". I'm enjoying it very much. I have been particularly enjoying the richer characterization of Lila, for example. I would keep reading if you stick with it, but yes, do what's right for the book.

I'm good with whatever path you choose. I've been enjoying it all so far.