Folks, I know that some of you are pacing and fretting, waiting for me to produce the next essay on Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels, but I am not in the vein; I have been consumed by the new semester and my free hours have gone into futzing with screenplays and with resurrecting an old novel and puttering about on a new one, and when I pick up something to read that isn’t work related it has been, for reasons I will eventually tie to POB, Anthony Trollope’s Barsetshire novels. I am two thirds of the way through The Last Chronicle of Barset and when that is done I believe I shall be released into a place where I can readily discuss the next Aubrey-Maturin novel, The Yellow Admiral.

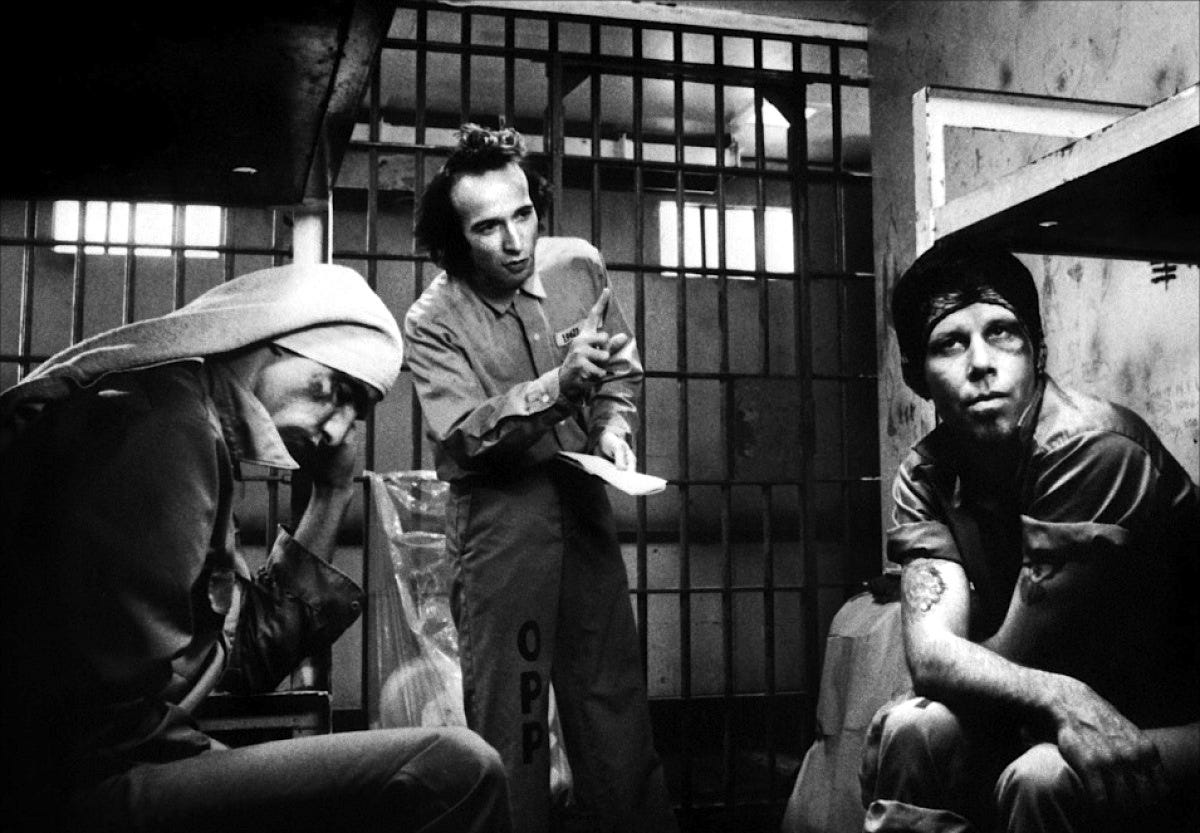

A couple nights ago I rewatched, for the first time in decades, Jim Jarmusch’s second feature Down by Law (1986). My fifteen-year-old, who is constitutionally allergic to anything arty or pretentious—that is, everything her dad likes—wandered in halfway and ended up staying to the end, enchanted, only occasionally repeating her usual mantra when she stumbles upon a movie I like: “What is this movie?” What it is is the cinematic dream of a middle-class kid from Cleveland who turned himself into an avatar of downtown cool, largely by deconstructing genre movies, compressing and unfolding them into a series of visual jokes and lyrical intensities. He’s like Tarantino if Tarantino had moved to New York instead of Los Angeles, only Jarmusch is less obsessed with re-inserting himself into the grindhouse thrills of his boyhood, more interested in art-qua-art. Jarmusch’s cinema can seem at times a little thin, which is not quite the same thing as shallow; there’s a lo-fi, ascetic quality to his movies that hollows out the genre tropes he plays with, in a neo-Brechtian manner. He’ll give you an archetypal figure from the dream-life of cinema, such as the Hagakure-guided assassin played by Forest Whitaker in Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), and subtract from him anything resembling psychology or backstory, so that we are confronted with the mere image of our own desire for such figures. While he is parsimonious with character and nearly comtemptuous of plot he can be lush with incidentals, like music, and of course visually. His favored cinematographer, Robby Müller, finds beauty in the decayed infrastructure of 1980s New Orleans or 1990s Jersey City without, I think, falling into the trap of ruin porn. The black and white photography in Down by Law is absolutely ravishing and stills like the one above could have been adapted from a painting by Raphael. Still, it’s possible to associate him as I’ve done with Tarantino as someone who works in pastiche, easy to parody him as a self-indulgent hipster who’s read a little too much Bukowski. What elevates his work?

Jarmusch remixes, brilliantly, the elements of Hollywood genre filmmaking that enchanted him as a kid, refracted through a neoexpressionist sensibility: the mysterious charisma of stars, enigmatic faces emerging from black shadows, the abstract violence of road films, etc. His eye loves ruins, decay, and wilderness. He takes road movies, film noir, gangster flicks, horror movies, love stories, etc., and either skips or undermines the beats we most take for granted in these genres. The jailbreak in Down by Law—the central event of classic escape films like The Defiant Ones (1958)—is practically an afterthought, and the climax of Ghost Dog transfers all its tension from the confrontation between Ghost Dog and his “master” from the duel itself to Ghost Dog’s resignation to death. He leaves out or subverts the “good parts” while dilating the moments that a conventional genre film keeps brief or leaves on the cutting-room floor.

This is taken to extremes in the 2009 film The Limits of Control—in my memory of it, at least. Here we have another cool Black assassin, this time played by frequent Jarmusch collaborator Isaach de Bankolé (the monoglot ice-cream vendor in Ghost Dog), in what I’d consider a minor work by a director intent on a minor cinema in the Deleuzean sense.1 All I really remember from this film is the obsessive repetition of a key type of interstitial thriller scene, in which the spy-assassin makes a contact and receives instructions regarding his target. Over and over we are treated to the spectacle of an impossibly handsome and dapper Bankolé sitting down at a table at one of a seemingly endless series of European cafes, to be briefed by one of a series of charismatic eccentrics played by the likes of Tilda Swinton and Gael Garcia Bernal. When he finally achieves his object and hits his target—a blustering politico meant to symbolize the arrogant folly of war-on-terror 2000s America, played by Bill Murray—the act is perfunctory and anti-climactic.

I suppose Jarmusch could be considered a postmodern filmmaker in his reflexivity—a preoccupation with the means of cinema as an end, so that concerns for story and character are afterthoughts.2 (Movie stars don’t need to be characters, after all—they have, as Norma Desmond told us, faces—and Jarmusch works regularly with the most interesting and most beautiful faces in show business.) I am trying to put my finger on the possibly imaginary distinction between artists of originality and those whose yearning to participate in the art they love is so strong that by remixing that art and its tropes they end becoming that art, made of that art.3

The exception that proves the rule in Jarmusch’s oevure would be his first feature, Stranger Than Paradise (1984), which he described as “a neo-realistic black comedy in the style of an imaginary Eastern European director obsessed with Ozu and The Honeymooners.” The grainy black and white deliberately leaches the frame of all beauty, though there are remarkable compositions, most famously the image of our heroes contemplating the blank white void that is Lake Erie in winter. The camera barely moves; each scene is like a little self-contained play, a single shot with fade-to-black intervals on either side. It’s less of a black comedy than an anti-comedy or a mock epic about three proletarian Quixotes, a road-to-nowhere story that slyly reverses Jarmusch’s fateful migration from suburban Cleveland to New York. To paraphrase Vivian Mercier’s snarky 1956 summary of Waiting for Godot, it’s a film in which nothing happens, twice.

Do original artists exist? Or are there only artists whose antecedents have been concealed by time or cunning? We all know there’s nothing original in Shakespeare but his handling of received materials—genre being one of them. Perhaps I am following a path back to Coleridge’s distinction between fancy and imagination—fancy (the 18th-century way of saying fantasy) being the whimsical recombination of actualities (a sphinx, for example: a lion with the head of a man) and imagination being the capacity “to idealize and unify.” Is this description or prescription? Isn’t unity in the eye of the beholder? At what point does the recombination of cinematic elements become the Jarmusch look, the Jarmusch style, even the Jarmusch metaphysics, indelible and immediately recognizable? Maybe it begins with Stranger than Paradise and falls off from there into self-parody? But there is strategy, too, in his overt recombination of genre elements, disconnecting the expected tropes from their antecedents, their normal rhythm, so that they become strange and marvelous objects in spite or because of the absence of plot, character psychology, and the other literary expectations too often superimposed on cinema.

The concern, of course, is personal. As I explore genre writing—mostly science fiction, though the novel I’m working on now is, like my published novels, something of a detective story—I wonder whether and to what degree my obsessions (or what Frank O’Hara calls “the catastrophe of my personality”) might idealize and unify my own recombination of genre elements with a modernism-inflected style. This in itself is nothing new under the sun, but I hope I have something different to offer readers than the mere eccentricities of my biography. Perhaps more broadly I hope that my misbegotten generation, Generation X, has something valuable to offer to a world that’s seemingly passed us by. Might we not serve as a yet-living archive of ideas and artifacts that offer some resistance to, on the one hand, the frictionless world of the extremely online, and on the other, the destructive narcissism of the Boomers?

Jarmusch, who just turned 70, is unquestionably a Boomer, but he’s beloved of GenX for the canniness of his cool and the seeming effortlessness of his synthesis of junk, pop, and art cultures. Above all he’s mastered the art of drawing to him the collaborators he needs to realize his vision, sometimes movie stars, very frequently musicians (John Lurie, Richard Edson, Eszter Balint, Tom Waits, Iggy Pop, RZA, and the list goes on). They are the living fragments drawn into the unity of his aesthetic, which flattens and cinematizes them. Maybe that’s the lesson for this fan of Robert Duncan, the self-proclaimed “derivative poet” who collaged quotations and translations into poems that could never be mistaken for anyone else’s.

I close with a quotation taken from the letters of James Schuyler, which I’ve been reading with great pleasure, in which he defends the aesthetics of artifice, to the point where one of Shakespeare’s most artificial plays takes on its own organic bloom: “Bigger works of art always seem to threaten to help one in some way or other, and therefore the fact that they exist is a part of the Social Good; As You Like It is just there, like the one red poppy across the lawn, pure excess of delight.”

By “minor cinema” I mean something analogous to Deleuze and Guattari’s minor literature: a work that subverts majoritarian thinking even as it works in the (in this case cinematic) language of that majority. Their paradigmatic example is Franz Kafka, a Czech Jew who wrote in German without being German and thus subverted Germanness; Jarmusch at his most interesting works in Hollywood genres while subverting those genres. For more on this topic see Gilles Delueze and Felix Guattari’s Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature.

Here I might digress on Jarmusch’s affinity for poetry, which pops up in most of his movies, most memorably and angularly in Dead Man (1995), a détourned Western in which a man named William Blake is mistaken for the poet and somehow more or less becomes him. There’s also Paterson (2016), whose eponymous hero is a poet, a bus driver whose devotion to his work is too pure to be much concerned with publication—in other words, even poetry as an object in Jarmusch’s films resists being turned into an instrument of plot.

I said I might digress, but I won’t.

Kafka once wrote, “I am made of literature; I am nothing else and cannot be anything else.” A boast indistinguishable from a cry for help.