Journey of a novel

Reflections on the first lap

If novel-writing can be compared to long-distance running, it’s generally the first lap—the first draft—that takes the longest. In the case of my present novel project, the end of the first lap is now in sight—I plan to have a complete draft before the end of the summer—but it’s the longest first lap I’ve ever taken. You might even say I’ve been running it for thirty years, ever since my late cousin Elvin “Al” Rasof first told me about the incredible life led by our mutual relative, the boxer Barney Ross. Dov-Ber “Beryl” Rasofksy was born in New York and grew up in the Maxwell Street ghetto of Chicago in the 1920s; his ultrareligious father was shot in a holdup, which led to his younger siblings being put in an orphanage. Trying to get them out, Beryl resorted to crimes petty and maybe not so petty (accounts differ as to what precisely he may have done for Al Capone, but he definitely worked for him), before he turned to boxing, changing his name to spare his mother the embarrassment (many Jewish boxers did this; my favorite example is Mushy Callahan, born Moishe Scheer). Barney was not a natural fighter—his father had hoped he’d become a teacher—but he was smart and quick and had an iron jaw, and the wins piled up. He was the first boxer to ever hold three championship belts (as a lightweight, light welterweight, and welterweight) simultaneously.

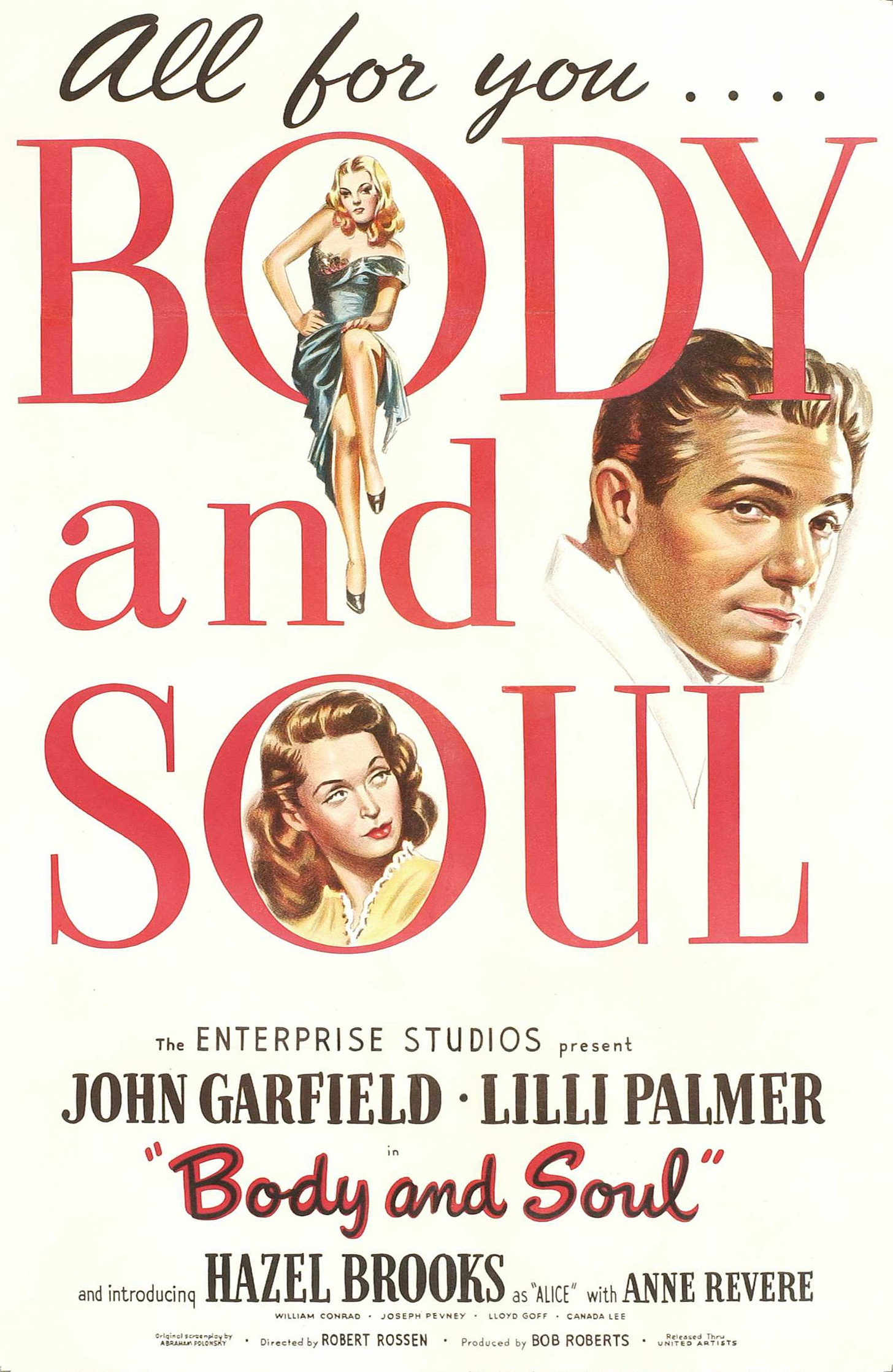

After his career ended, he was at loose ends: he opened a nightclub in the Loop, gambled compulsively, and discarded the nice Jewish girl he’d married, Pearl Siegel, for a shikse showgirl named Cathy Howlett. The war seems to have come as a relief. He became a Marine at age 31 and won the Silver Star for his actions in a gruesome battle on Guadalcanal, killing dozens of Japanese soldiers in his single-handed defense of three wounded comrades. He was dosed with morphine for a case of malaria and became an addict, but eventually kicked the habit at a federal drug treatment center and became an anti-narcotics advocate who testified before Congress about the sufferings of addicts. The noir classic Body and Soul was loosely based on his life, and there was another film made about his struggles with addiction called Monkey on My Back. I tracked down a copy of Barney’s autobiography, No Man Stands Alone and read it repeatedly. And because at that time I still thought exclusively as a poet, albeit a narrative-curious one, I tried to capture Barney’s life in a cycle of poems that I called Maxwell Street Sonnets. Here’s one:

I can still taste my blood. I was David. In the limed ring’s glare, Lugo’s body mirroring mine, a blink of pain. Naked each night in the blinds’ light, I make my study. Triphammering on the balls of my feet, muscles strung on the guitar of my arm, flamenco golem for a fist, I beat bruises in blue air, face a feint. No harm comes to the anointed. Every alley, every bit of broken glass, Father’s beard-- these gloves ain’t packed with sand. I keep no tally of big guys I’ve fed dust. See how I’m feared, how the bell and swell washes away shame and pride. Lord, let me stay David. Keep fame.

Of all the traditional forms the sonnet is most closely identified with lyric, and especially with the love poem. That doesn’t stop poets or their readers from collecting them into narratives—we will never stop trying to discern the story we infer from the cycle of Shakespeare’s sonnets, ordering and reordering them as the whim takes us. Looking back at my own little cycle I can discern my ongoing fascination between the lyric impulse on the one hand and the impulse toward narrative on the other. Synthesized, those impulses can create a kind of drama. In Shakespeare’s plays, the narrative is constantly interrupted by brilliant lyrical investigations of the inner life of Hamlet or Viola or Portia or Lear—soliloquies that bring the narrative to a screeching halt, reorienting or restarting it from our new conception of how that character sees themselves.

So that was the zeroth lap. I never published any of those poems in magazines, that I can recall, but they did make up the bulk of my portfolio when I applied for a Stegner Fellowship in 1999. I spent my two years in the Bay Area fighting what felt like a guerilla war against the ghost of Yvor Winters, writing elliptical, abstract poetry that could not have been more different than the sonnets I’d been accepted for, culminating in one of my stranger books. But I’m too romantic or sentimental to ever put lyricism entirely aside, and it turned out I wasn’t done with the sonnet either. After Stanford I spent some of the happiest years of my life in Ithaca, New York, working on my PhD and falling in love with the woman who became my wife. In spare moments stolen from my dissertation I wrote the ventilated sonnets of Severance Songs, which ended up winning the most substantial prize of my career thus far. They were love poems and pastoral poems, written against the backdrop of 9/11 and the subsequent military adventurism that laid the groundwork for our authoritarian present. In 2018 I returned to the Maxwell Streets Sonnets as a component of “Lightweight,” a digital essay about Barney, my father, and the vulnerability and resilience of the Jewish male body.

Still I’m not done with Barney. The novel I’m writing now would not have taken on its present form without the belated discovery of his lifelong friendship with one of history’s most notorious schlimazels, Jacob Rubinstein aka Jack Ruby. I don’t think I knew about this friendship before I read Douglas Century’s 2008 biography of Ross, in which Century refers to Ruby as “the Jungian shadow of Ross. In the latter we see the controlled, scientific harnessing of violence; in the former its most undisciplined, impulsive manifestation” (19). Another page from the book was equally arresting: it depicts Barney Ross at the Cotton Club on November 30, 1936, when the Champ was at the height of his powers. Sitting next to him is J. Edgar Hoover. And at the bottom of the page, after a description of the glamor in which the fistic enterprises of this Orthodox Jewish ghetto boy had been immersed, this sentence: “Like the Golem—that mythic man of clay who was created by a kabbalist to save the Jewish people and winds up running amok—Ross became a prisoner of the very restless impulses that had catapulted him to greatness” (90-91).

Thank you, Mr. Century. In those two lines you gave me the novel project that has obsessed me for the past half-dozen years.

Jack grew up alongside Barney in equally violent, dysfunctional circumstances. His path through life shadowed the champ’s at nearly every turn, culminating on that fateful November weekend in 1963 that began with the assassination of JFK and ended with Ruby assassinating the assassin. Ruby is often seen as a footnote to the story of Lee Harvey Oswald (Norman Mailer more or less treats him as such in his behemoth novel Oswald’s Tale); but that story is so epic, and seems to have so much to say about the American Century and what it became, that even a footnote might warrant whole films and novels unto itself. A story began to catalyze in my mind of a fictional FBI agent, on special assignment from the Director himself, who goes to interview Jack Ruby where he lay dying of cancer in Parkland Hospital in December 1966, to make one last attempt to discover the truth about why he shot Oswald in basement of Dallas police headquarters in front of the eyes of the world. But Ruby, whose mind had been in a fragmentary state since the day Kennedy was shot and possibly for long before, has a different question to ask, a different story to tell. He and Barney Ross were so close, so similar—both in their way gave all they had to show the world that “Jews have guts.” Why, then, should Barney be a hero, while he, Jack, was a villain or something even worse—a cudgel with which the world’s antisemites might destroy the Jewish people? He was, he believed, the hapless dupe of a conspiracy—not a conspiracy to kill the President, but to bring about a second Holocaust, right there in Dallas.

Don’t write a novel if you don’t have a taste for obsession. For the past six years I have gone down a dozen rabbit holes: the history of boxing, Al Capone’s Chicago, the celebrities like Al Jolson with whom Barney palled around, the Pacific theater of World War II, the Narco Farm in Lexington, Kentucky where Barney kicked his morphine habit, Dallas’s neighborhoods and nightlife. The biggest rabbit hole of all, of course, is the JFK assassination; as many others have discovered before me, the Warren Report reads like a great novel in itself (George Oppen compared it to Ulysses, with Jack Ruby as its Leopold Bloom), and there are dozens if not hundreds of books, movies, and TV shows in which Ruby is a player large or small, from the 1992 film Ruby starring Danny Aiello to Stephen King’s novel 11/22/63 (and the subsequent miniseries adaptation) to The Umbrella Academy. Every writer of historical fiction faces the problem of when to stop researching, when to start writing. I have been aided in my thinking around this question by the work of my Lake Forest College colleague Ben Goluboff, the author of Ho Chi Minh: A Speculative Life in Verse and Other Poems, and several other collections of what he calls “speculative biography.” Here again the lyric and narrative impulses intertwine and collide as Ben resurrects sometimes notorious, sometimes obscure figures like the scuptor Lorado Taft or General Curtis LeMay, rescuing their humanity from the ossifications of history. It’s a way to hold history in lyric suspension, without assimilating any of its particulars into a generalizing ideological stance.

The biggest challenge of writing historically is to avoid the cheap irony that comes from knowing the fates of the figures you’re writing about: you have to believe, whatever ultimately became of them, that they might have made different choices, that things might have been otherwise. The obstacle to that in my case is the biggest rabbit hole of them all—not a rabbit hole but a wound blown through all our lives. I am speaking of the massacre perpetrated by Hamas on innocent Israelis on October 7, 2023, and on the disproportionate, genocidal response of Netanyahu’s government from that day to this. Jack Ruby tried to avenge the death of JFK, as if killing Oswald could undue the rupture in the American Century caused by the President’s death and restore the sense of invulnerable destiny Kennedy’s charisma had emobdied. What the IDF has done and is doing strikes me as similarly futile, and similarly immoral, but on a far more calamitous scale. It’s a cliche to say that Kennedy’s death brought about the end of America’s innocence, however renewable a resource such innocence has proved to be—but it did bring us to a fork in the road. Down one path is a reckoning with the mortal complexity of the American story, which cannot be reduced to either atrocity or righteousness. The original sins of slavery and of Native American genocide can never be erased, nor their ghosts placated, yet I still believe in the promise of equality that’s written in our founding documents and deeds (among which I include the Gettysburg Address, the New Deal, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964). The other path, of course, is the one we’re following now: the path of chauvinism, denial, paranoia, and authoritarian promises of “greatness.” It might have been otherwise. It might yet be otherwise. Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation.1

I can’t write about Jews, Jewish men, Jewish men who forged their paths through violence, without thinking about Israel-Palestine. This is all the more the case with Barney Ross, a militant Zionist who ran guns to the Irgun during the Arab-Israeli War. Were his actions the seeds of genocide in Gaza? Was there an inevitable pathway from the struggle to create a Jewish national home (in the words of Chaim Weizmann as expressed in the Balfour Declaration) to the dehumanizing apartheid to which Palestinians have been subjected? Must history’s victims become perpetrators? I have to believe that none of this was inevitable, nor will the deaths of malnourished children that get reported tomorrow have been inevitable. I condemn the actions of the Israeli government, as I condemn those who would murder Jews on the streets of Washington, DC, or anywhere else. I condemn violence. At the same time, I feel compelled to try and understand it, the fear and humiliation that eats the soul, that seems to demand of a man that he lash out instead of coming to terms with his own mortal limits. That’s what writing this novel has become.

Ross and Ruby are particles of possibility suspended in the narrative solution of history that has relegated the former to heroism and the latter to infamy. My novel tries to be true to the lyric possibility within each man, the subjective dignity that resists their golemization by the force of history that would turn David into Goliath. I hope as well that it tells an entertaining story, but it’s become my tool or vessel for transforming, in my own mind at least, the helpless passivity I can feel in the face of horrors into agency, wisdom, and persuasive action.

I just have to finish the damn thing, first.

A phrase attributed to the late great Alasdair Gray, whose magnum opus Lanark I recently read with astonishment and pleasure. A kind of Glaswegian mashup of Michael Moorcock and James Joyce.

Fascinating subject matter. Hope to read the novel someday.