I am preparing for the fall semester, yes I am: writing syllabi, emailing colleagues and students, getting ready to leave this calamitous (yet for me, oddly productive) summer behind. With unusual ruthlessness I set and achieved my personal goal of finishing and revising my science fiction novel SKIN & BONE by early August, so that I could rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic of my mind to receive its new passengers. This fall I will be teaching:

Introduction to Creative Writing, my workhorse course that I’ve taught every semester since I first started at Lake Forest College in the dim dear days beyond recall (2007). The trick with this course is to engage with and improve the writing of the majority students who are taking the course to satisfy a requirement but who aren’t otherwise interested in literature, while encouraging and challenging the future English majors and the weirdoes who are serious about writing. (Roberto Bolaño is supposed to have said that “Reading is more important than writing,” and I agree with him; all of my creative writing courses are secretly courses in reading, in bootstrapping some familiarity with the building blocks of narrative and poetry, and, I hope, in pleasure. Another out-of-context Bolaño quote: “Reading is pleasure and happiness to be alive or sadness to be alive and above all it’s knowledge and questions.” Yeah.)

Fiction Writing. For some reason this is the first chance I’ve had to teach my department’s intermediate fiction course (as opposed to more specialized courses in writing science fiction or novels, or the multi-genre courses I regularly teach). For my main textbook I’ll rely upon Janet Burroway’s old standby, but it’s been more difficult to choose an anthology of short stories with which I’m familiar enough that I’ll be able teach them in a nuanced way. Oddly, I found myself choosing between two anthologies that were both published in 2004: Ben Marcus’s The Anchor Book of New American Short Stories and Alexander Steele and and Thom Didato’s Gotham Writers’ Workshop Fiction Gallery. Were I actually teaching this course in 2004, there’d be no question but that I’d choose the former, with its violently postmodernist battery of stories by the likes of Wells Tower and Aimee Bender, on a holy mission to shatter conventional preconceptions about what a short story is and can do.

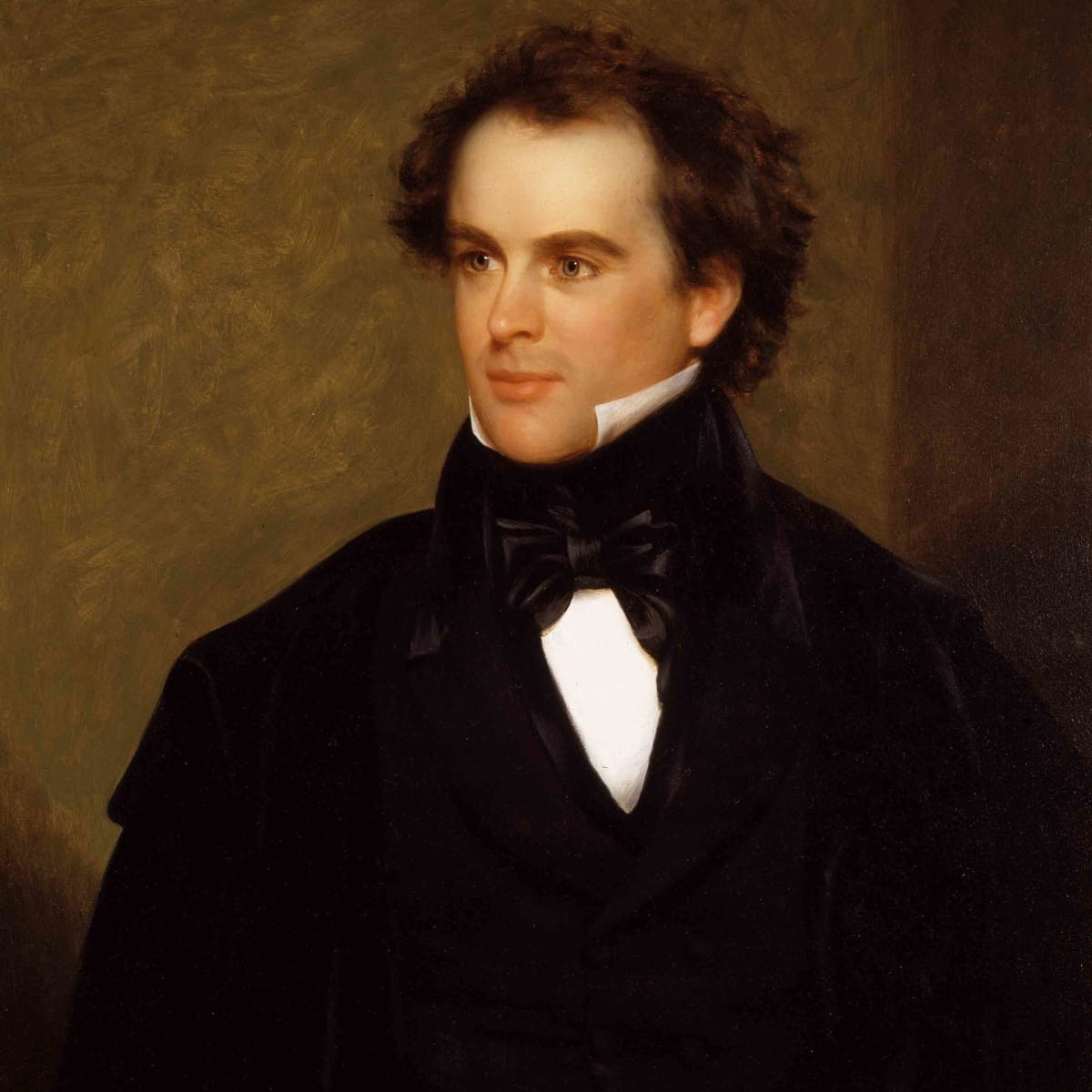

In hard old 2021, however, I’m more inclined toward the frank humanism of the selections in Fiction Gallery, in which selections from ZZ Packer, Pam Houston, Jhumpa Lahiri, and John Cheever, et al, are bookended by Chekhov’s “A Trifle from Life” and Hawthorne’s “Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment” (which I ought to have read in the process of composing Hannah and the Master for the sheer coincidence of it, but never mind). The anthology is built around the plausible premise that the influences of Chekhov and Hawthorne stand behind the two major poles or schools of American fiction: the “character caressing” slice-of-life Chekhov versus the plot-driven, gee-whiz genre gothicism of Hawthorne. I expect most of my students to be Hawthorneites (Heideggerians?), which is fine, but even as I re-embrace genre fiction, I find in middle age that character has become my central fascination, so I’ll be gently nudging them to at least appreciate the Chekhovian strain.

Watchmen and Society. This is a brand-new course, a first-year seminar for brand-new Lake Forest College students, and I’m quite excited about it. We’ll start out reading the 1986 graphic novel, along with Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and in the second half of the semester we’ll focus on the HBO limited series created by Damon Lindeolf (a must-see). I was fifteen with Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen came out (I first read it in monthly installments, like any other comic book) and like most comics fans of my generation I was permanently altered by its revisionist take on superheroes (see also Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, though at the time I didn’t discern the difference between the right-wing politics ironically critiqued by Moore and Gibbons from the right-wing politics enthusiastically endorsed by Miller). Lindeolf’s series is both a sequel and a revision (or “remix”) of the original graphic novel, reframing its critique of vigilantism within the real history of racialized vigilantism (and policing) in the U.S. The first episode begins with a harrowing depiction of one of the most notorious incidents of racialized vigilantism in our history, the Tulsa Race Massacre, one hundred years old this year. LOTS to talk about. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Here in the Chicago area the signs of the deep trouble we’re in have been a bit more subtle than they’ve been out West—we’ve mostly been spared the wildfire smoke, and there have been hot temperatures but nothing that seems too far out of line for a Midwestern summer. There was an intense thunderstorm last Wednesday with 65 mph winds that knocked out our power for twelve hours; Lake Michigan is down from its record high of last year but it’s still 22 inches higher than normal, and it’s eaten a considerable quantity of Evanston’s beaches. Today the weather is perfect, sunny and in the mid-seventies; I can hear birds chirping from my window. Business as usual.

If one didn’t read the news, one could pretend that things are normal. But of course, things are normal, aren’t they? It’s just that the word “normal” no longer means what it did. The word normal derives from the Latin for “carpenter’s square,” which ought to remind us that the normal is always human creation, as there are no straight lines in nature. The normal is something we build. Or break.

My title refers of course to the famous MacGuffin from Casablanca, the “letters of transit signed by General de Gaulle. Cannot be rescinded—not even questioned!” Leaving aside the illogic of this—why should the Vichy government, let alone its Nazi masters, respect a document signed by the leader of the Free French?—the letters function as a get-out-of-jail-free card, a means of perfect escape from an untenable situation, enabling the flight at the center of the word refugee. In the film, that flight is inseparable from fight—the noble Viktor Laszlo is not simply saving his own life, but saving it for the purpose of continuing the struggle against an implacable foe—one that, in 1941, the year of the film’s release, was by no means certain to lose.

Creative writing today means composing one’s own letters of transit—means of flight and fight—negotiating the difficult transition from the jerry-built “normal” of the neoliberal capitalist climate disaster toward something more uncertain, grounded in the lived experience and needs of ordinary people learning to care for their particular patch of earth and each other—a flight toward, and fight for, wherever one already is. Looking back over this post, I note a theme of the deconstruction of heroism, whether in the form of the American gothic story or in the white supremacist ideology hiding behind the mask of many superheroes. No one is coming to save us, but writers can start telling stories that de-center the heroic in favor of the textures of actually existing life, the only ground from which a livable future is likely to emerge.