I was strangely put in mind of Edward Fox, the unfortunate envoy who serves as foil or counter-hero to Jack Aubrey in The Thirteen Gun Salute, by the performance of Ethan Hawke as the songwriter Lorenz Hart in Richard Linklater’s new movie Blue Moon, which Mrs. Rarebit Fiend and I took in at a rather dismal cineplex not far from headquarters. Bear with me now. The film is very much a character study, taking place almost entirely within the confines of Sardi’s, the legendary Broadway hangout, on the evening of the triumphant premiere of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical Oklahoma!, March 31, 1943. “Larry” finds himself consumed with jealousy and contempt, sneering at the exclamation point and the middlebrow lyrics of Oscar Hammerstein II, who has replaced Hart after twenty years of partnership because Rodgers can no longer put up with his alcoholic instability. The real Lorenz Hart was a very little man, 4’10” according to Wikipedia; Linklater uses an inflated-looking suit and camera wizardry to cut the 5’10” Hawke down to size. Oozing a continuous monologue blending poetry and obscenity, underneath a dire comb-over and walking with an antic waddling gait, Hawke’s Larry Hart is a kind of midcentury Alexander Pope—a witty, diminutive outsider who helped to define the culture of his era. Hart accomplished this by writing the lyrics to deathless songs like “Isn’t It Romantic,” “My Funny Valentine,” and of course the title number, which Larry despises but which follows him around like an ankle-biting dog. Like Pope, Hart is a tolerated outsider, though not for being Catholic; Larry Hart is gay, or as he puts it, “ambisexual—I can jerk off with either hand.” Not much happens, plotwise: Larry talks to anyone who will listen, whether it’s the sympathetic oaf of a bartender played by Bobby Cannavale, a piano-playing soldier on leave (Jonah Lees), and in a delightful surprise, E.B. White (Patrick Kennedy). When Rodgers and Hammerstein arrive in triumph, Hart’s disdain turns to obsequiousness as he begs his erstwhile partner for another shot; they have a painful colloquy on a stairway landing, with Rodgers literally having to shake the needy, alcoholic, resentful Hart from his coattails before he can ascend to immortality. “You’re very talented, Larry,” Rodgers tells him. “That’s never been the problem.” Shaken, Larry retires to the coattroom for a heart to heart with Elizabeth Weiland (Margaret Qualley), a beautiful twenty-year-old Yale student with whom the middle-aged Hart feels himself to be in love. She does love him, but “not that way,” giving Larry another chance to riff on his favorite line from Casablanca, spoken in disbelief by another middle-aged man confronted by the purity of a young woman’s desire: “Nobody ever loved me that much.” She ends up leaving with Rodgers, her eye on the main chance. Hart, we know from a prologue, will die six months later of pneumonia contracted while wandering drunk down rainy alleyways of New York City, alone if not unmourned.

So what does any of this have to do with the copper-bottomed, give-em-a-broadside adventures of Captain Jack Aubrey, RN, and his particular friend Dr. Stephen Maturin? Maybe nothing more than the coincidence of watching the movie on the same day I finished a reread of The Thirteen Gun Salute. This time, I was struck forcibly with a sense of compassion for the rather dislikable character of Mr. Edward Fox, the envoy whose prickly sense of his own distinction and anxiety for recognition lead him first to alienate and then to abandon the crew of the HMS Diane, sailing off into a typhoon from which he never returns. I’ve already written about this novel, and focused pretty closely on Fox; what more is there to say?

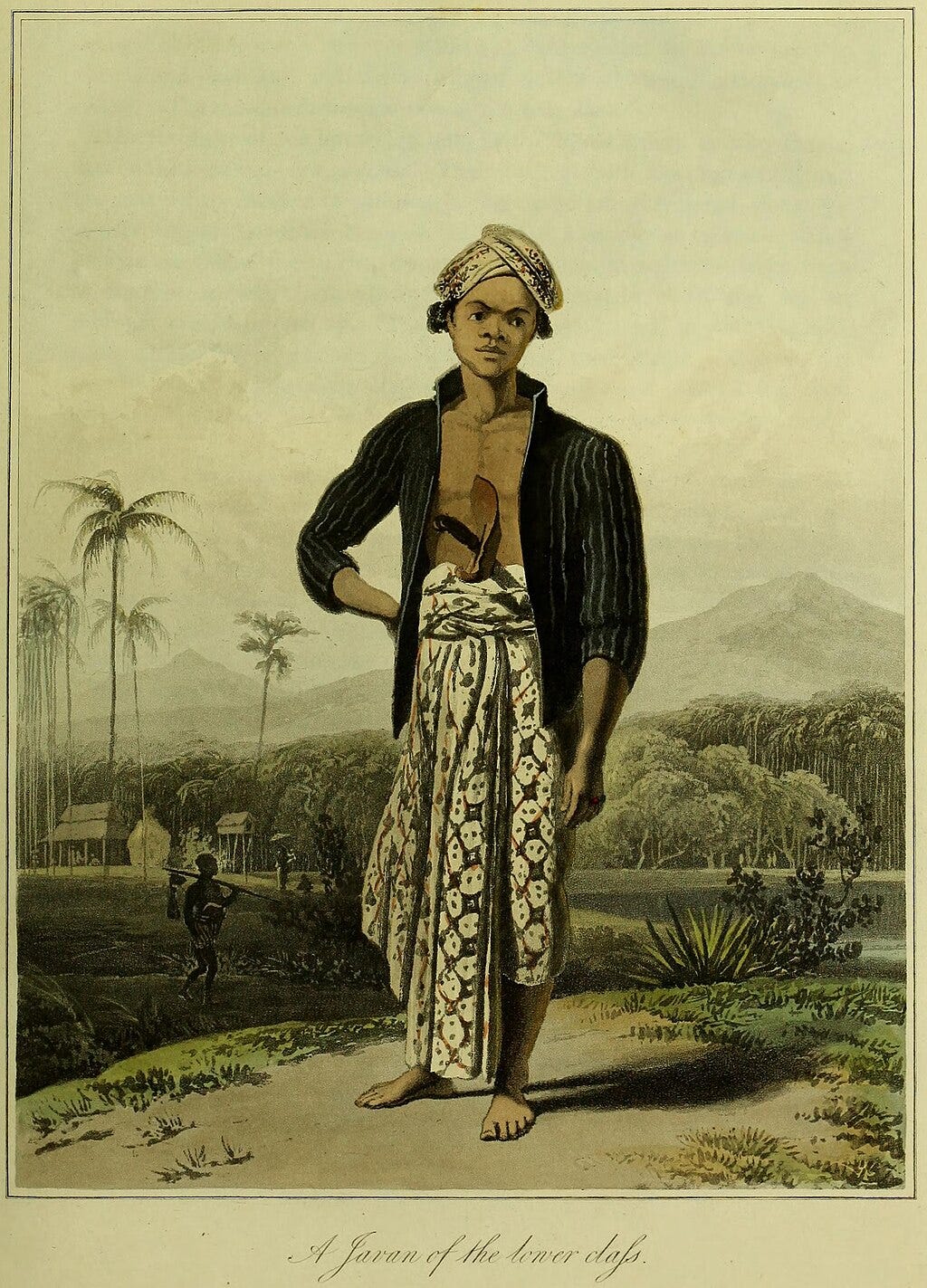

To answer these questions, let us turn to one of the real historical figures who pop up from time to time in the Aubrey-Maturin series, the appealingly named Stamford Raffles, of whom the fictional Fox is partly modeled. Raffles was the son of a sea captain who voluntarily ended his involvement with the slave trade; at the age of 14 he apprenticed with the East India Company, and in 1805 when he was 24 he was appointed secretary to the new governor of Penang, Philip Dundas. (Yes, one of those Dundases: a nephew of Melville, onetime First Lord of the Admiralty, whose fictional brother Heneage is Jack’s good friend.) Leveraging his knowledge of Malay language and culture, without advantages of birth or patronage, Raffles rose swiftly, becoming lieutenant-governor of Java after the British defeated its allied Dutch and French occupiers. Something of a technocratic visionary, he introduced a land-revenue system fairer than the tenant system of the Dutch, pursued educational reform, and abolished slavery. But he was also an intellectual and something of a romantic. His 1817 book, The History of Java, is both a justification of imperial practices and a sensitive work of ethnography and history. He explored the ancient Buddhist temple at Borobudur—the inspiration, it would appear, for the orangutan-haunted temple that Stephen Maturin finds at the top of the Thousand Steps—one of several moments in the series in which an encounter with the wonders of nature is conflated with religious experience. His interest in natural philosophy may not have been as intense as Stephen’s, but he did give scientific names to at least two species, Macaca fascicularis and Tragulus kanchil. He is, in short, the face of British imperial administration at its most attractive—or seductive.

Fox’s deep knowledge of Buddhism (we are told he once “read a paper on the spread of Buddhism eastward and its subsequent relations with Brahmanism and the Muslims” at a meeting of the Royal Society), his knowledge of Malay and other languages, and his genuine passion for Javanese and Malay culture are all attractive qualities taken from Stamford Raffles. His less attractive qualities are described by Sir Joseph Blaine as deviations from what we know of Raffles’s character:

“Of most unusual parts; and yet he has never been appreciated at his full value. Always acting, temporary appointments – always moved on to some other administration. Perhaps there is some fault of manner … a certain unorthodoxy … a certain bitterness from want of recognition. But there are undoubtedly remarkable abilities, and he might have been made for this particular undertaking. He is, by the way, a friend of Raffles, the Governor of Java, another interesting man.’

What is the nature of Fox’s bitterness? In my original essay, I wondered whether it had something to do with his sexuality; my recent rereading seems to confirm that idea. His hatred of the traitor Ledward (whose very name, “Edward Ledward” suggests one who leads an Edward—Fox’s own first name—down the primrose path), to the point of wishing to see him “peppered” (a grisly form of execution in which the victim’s head is stuffed into a sack of peppercorns and then beaten until they are dead) seems too intense to be anything but the hatred of a lover scorned. They appear to have met in Penang, and likely had a relationship there; Fox thus has reasons for taking Ledward’s treason against the British state extremely personally. (Raffles, for what it’s worth, was married twice, but had several male protegés, one of whom, Thomas Otho Travers, was his bosom companion for twenty years.) Perhaps Fox blames his failure to rise in his diplomatic career in part with having associated with a traitor; perhaps sexual shame is a sufficient explanation. During the long voyage of HMS Diane to Pulo Prabang, Fox’s condescending air of superiority and inflated sense of his own importance fails to make him much liked by the officers and crew. His one companion, a young man named David Edwards (why is everyone in this story named Edward?), is oppressed into muteness by the force of Fox’s self-regard, nor can Fox partake in or even appreciate Jack and Stephen’s music or the singing of the sailors dancing nightly on the forecastle. (An inability to appreciate music is nearly always a marker of poor character in the Aubrey-Maturin novels.)

Fox is an intelligent man, and a lonely one. He consults frequently with Dr. Maturin in his professional capacity as a sop against that loneliness, and maybe something more. In Lois Montbetrand’s article “Bells in the Tower,” which is about O’Brian’s anachronistic incorporation of an A.E. Housman poem into the novel,1 she reproduces a note with that heading from O’Brian’s manuscript papers. The words, I believe, were intended to be voiced by Stephen Maturin:

“Hypochondriac self-centered self-hater; and I have often observed, that your self-hater generally manages to retain his self-esteem in relation to others by means of a general denigration: it is as though he saw clearly & no doubt rightly that he was a worthless scrub but that nevertheless all the rest (or all those in his immediate view) were even more worthless, even more scrublike. They are I am told the bane of confessors in the old establishment—interminably wordy—the last & lowest of sinners, apart from any (illegible word) of humanity.”

My original post on The Thirteen Gun Salute began with a consideration of the meaning and etymology of scrub, so I’m pleased to discover O’Brian himself defining the term here so acutely. This may be the key, then, to Fox’s character: his self-hatred is such that it sets him apart from humanity. There is no necessity for his sexual orientation alone to explain this, but his extraordinary sensitivity to slights, and his naked hankering after the thirteen-gun salute of the title (the number of guns fired to honor a king’s representative) suggests that he is a man who feels himself to be socially flayed, desperate for compassionate protection. He is a hard man to like, but I feel sorrier for him on this read than I did previously. His scrubness makes him the lowest of sinners, but he has touches of nobility as well. Even his jealous hatred of Ledward makes him more human.

Which brings me back to Lorenz “Larry” Hart and Blue Moon. Hart is a more lovable character than Fox, and of course he’s a songwriter with a deep feeling for music. But he has something essentially in common with the embittered envoy. If we push the boundaries of speculation just a tad, we can surmise that Fox and Ledward once had an intimate connection—you might even say they were particular friends. Larry Hart also has a particular friend with whom he had an intimate working relationship, something that him capable of accomplishing artistic feats he could never have managed on his own. That of course is Richard Rodgers. Rodgers and Hart, Ledward and Fox, Aubrey and Maturin! One of these pairs of particular friends is not like the others, if only because they are never seriously tempted to betray one another.

But when a particular friend is no longer treated with kindness and particularity? When one betrays the other for the sake of his own ambition, even or especially if both parties have ambitions that their continuing partnership puts out of reach? What remains? Bitterness and desolation, alienation from humanity, and in Larry and Fox’s case, a sour and demanding performance of amour propre that solicits our disgust—or our compassion.

The partnership of Rodgers and Hart was endlessly creative; for more than twenty years they made indelible contributions to the American songbook while producing a stream of Broadway hits. The partnership of Aubrey and Maturin is, in its own way, equally creative. Without Jack, Stephen would likely have remained a penniless physician, increasingly embittered by the failure of the 1798 Rising; he would not have discovered his calling as a student of human as well as animal nature, nor would he have become the deadly effective intelligence agent who ultimately triumphs over (to the point of literally dissecting) Ledward and Wray. Jack would have still been an enterprising commander, but without Stephen to advise him and protect him from land sharks and Jack’s cruder impulses it’s doubtful that he would have enjoyed his prize money for long, nor would his marriage to Sophie be as happy as it is, if it happened at all.

The closest Jack and Stephen come to mutual betrayal is early in the series, in Post Captain, when they almost fight a duel over Diana—jealousy being a reliable agent of chaos in a friendship. We can only speculate whether the break between Ledward and Fox may have been over something similar, though Fox’s relish at Ledward’s discomfiture being caused by his affair with the Sultan’s gazelle-like Ganymede is suggestive. Unfortunately we never really get a clear look at Ledward in the series—he is more like the unseen cause of various effects—but we do get a vivid sense of his lover and subordinate Andrew Wray, who like Fox is a “man of parts” with self-destructive tendencies. Fox may feel himself to have been replaced by Wray, though his rage seems directed more at Ledward, just as Lorenz Hart saw himself replaced by Oscar Hammerstein II, an inferior talent. Jack and Stephen depend on one another, and I would not be the first to compare their partnership to a marriage. But though they sail together, each under the other’s nominal command (Stephen, remember, becomes the owner of Surprise), they do not depend upon one another professionally. They amuse one another; they are musical partners. Their bond is, above all, moral. Stephen educates Jack about Ireland, about Catholicism, about slavery and other ills he would otherwise be blind to. Jack’s friendship binds Stephen, a born isolato, more tightly to common humanity.

In the case of Rodgers and Hart, the friendship has outlived its usefulness—at least from Rodgers’s perspectives. The caustic wit and irony of Hart that was so in tune with the spirit of the Twenties and Thirties fell out of fashion in the earnest, buy-war-bonds Forties. But while Rodgers has his regrets about cutting off his old partner, for Hart it’s a catastrophe. Hart gave Rodgers edge, but Rodgers gave Hart humanity, and now that’s lost. No wonder he buoys himself briefly with the fantasy of a young woman’s love; no wonder that he dies miserably and alone. As for Fox, oddly, it’s his victory over his former partner that destroys him. The mask of the white man’s burden slips from his face; his amiable interest in Eastern religions disappears, and all that’s left is a hollow man inflated by royal prerogative. He’s so desperate to exercise it that he impulsively abandons ship, leading to his demise.

The verse in question:

When the bells justle in the tower

The hollow night amid

Then on my tongue the taste is sour

Of all I ever did.

What a strange verb justle is! I like how it seems to blend jostle and hustle and also just—it contributes to the acid taste of regret on the speaker’s tongue.

Hart is the only American songwriter whose complete lyrics I own (sorry-not-sorry, Unca Bob & Unca Lou), but I regret his previous movie appearance (in which he played Bud to the WASP's Abbott) & will proceed cautiously towards this one.

If you'd like to share my pain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FpFyr64Y7Ag