The Clod and the Cloud

Techno-optimism and its discontents

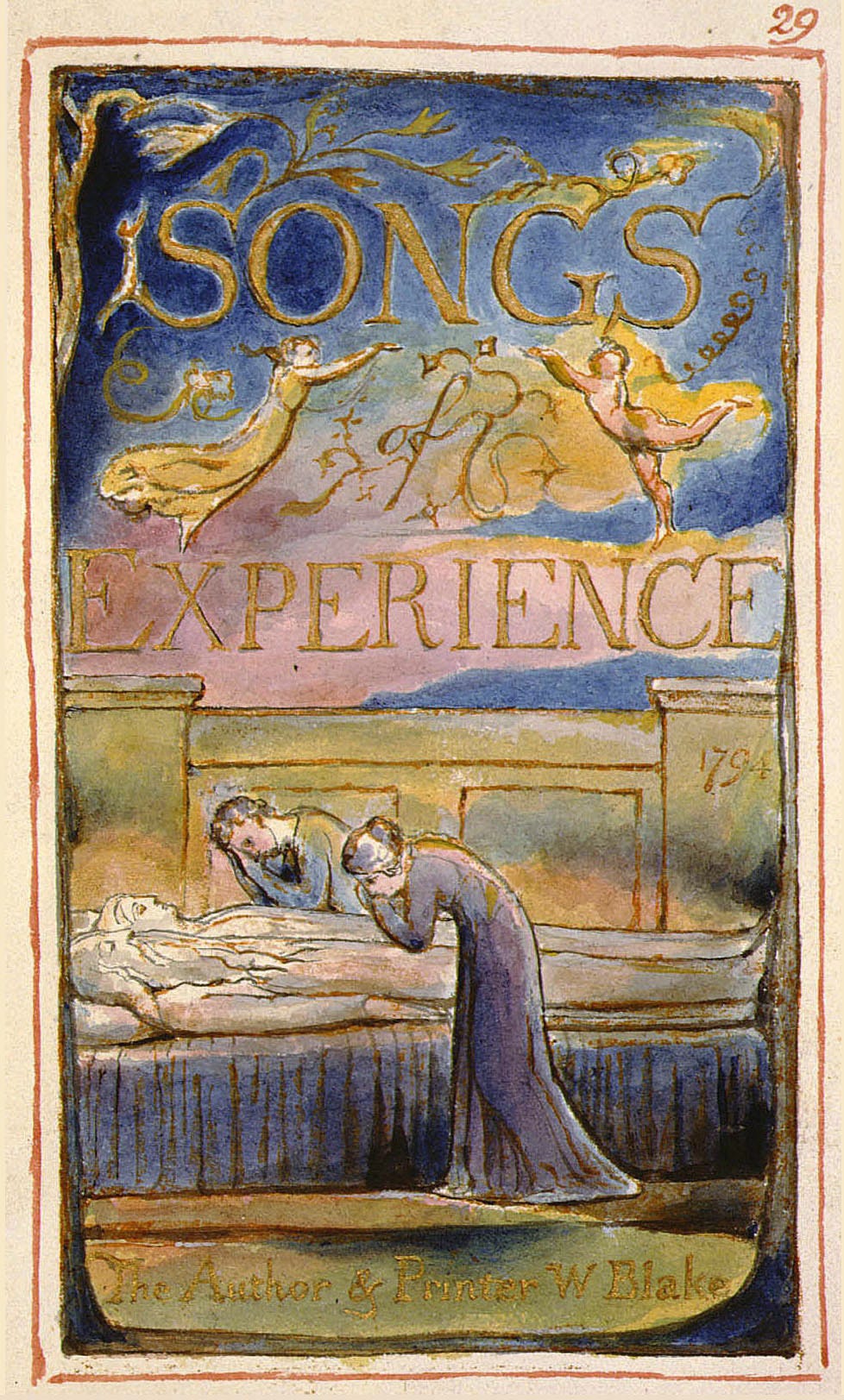

For a roughly fifteen-year period—from the dawn of Netscape in the mid-Nineties to the ramp-up of algorithmic social media and the proliferation of the smartphone—the Internet felt like a playground, a frontier, a field of liberatory potential. Now it feels like a strip mine. Enshittification is the term of art for the extractavist logic that has governed online experience since about 2010. We have gone from innocence to experience, as the early Internet of the pre-smartphone era belatedly gave way to our discovery of the material basis of the thing as a series of tubes that drains electricity, water, and our precious attention. William Blake saw it coming:

THE CLOD AND THE PEBBLE

‘Love seeketh not itself to please,

Nor for itself hath any care,

But for another gives its ease,

And builds a heaven in hell’s despair.’

So sung a little clod of clay,

Trodden with the cattle’s feet,

But a pebble of the brook

Warbled out these metres meet:

‘Love seeketh only Self to please,

To bind another to its delight,

Joys in another’s loss of ease,

And builds a hell in heaven’s despite.’ Blake wasn’t thinking of Elon Musk, probably,1 but the poem does accurately prophesy the shift from the clod’s earnest idealism (“information wants to be free”) to the pebble’s self-satisfied cynicism in binding us to its platforms, its profit-seeking, and the dopamine-driven curation of the worst impulses of our monkey-minds. Again and again we make this basic mistake, hailing the transformative power of technology while sparing almost no thought for the capitalist imperatives that pay for that technology. Nothing is more insidious than the model we’ve adopted whereby instead of paying for services like email, news, etc., those things are delivered to us “for free” while our data, attention, yea brethren our very souls, are pickd over and harvested.

So-called Artificial Intelligence (or as my daughter incisively renamed it, Other People’s Intelligence) seems like the latest turn of the worm, proving that the cycle of innocence-to-experience may run shorter and shorter without ever actually ending. We hear extravagant promises about how it will revolutionize our lives, and extravagant fears of how it will destroy them. But I’ve seen this movie before.

In 1999 I arrived at Stanford, giddy with astonishment at having somehow gotten myself a Stegner Fellowship in poetry. The stipend was munificent, but the cost of living in the Bay Area was exorbitant even then, and I found I couldn’t afford the rent on my crappy room in the back of a two-family house in Atherton without a part-time job. I found one at an outfit called Surprise.com.

It was the beginning of the collapse of the bubble that was the first dot-com boom, but in Palo Alto, denial was the favored cologne. The brainchild of a couple of former HP execs, Surprise.com was a startup website that was going to make money selling gift ideas directly to consumers. I recently discovered a February, 2001 article from Palo Alto Online that sums up what is now only a fevered memory:

The whole concept of Surprise.com rests on the idea that people don't know what they want. Or rather, that people don't know what other people want. Surprise.com, plainly put, is a site for gift givers to find the perfect gift idea.

…

At the site, visitors choose from a variety of quirky descriptive categories--from "Gifts For Francophiles" to "Loves Their Car." Each category lists gifts of all prices that others have deemed suitable for a person with that particular quality. Some of the more amusing ideas include: a fog machine for the person who has an "Unusual Sense of Humor," a maid service for "Someone Who Works Too Much," or, for the person who is "Adventurous," night vision goggles. A link takes users from the gift idea to a variety of sites on the Internet where they can purchase the item.

Ah, the “Adventurous”! By the time the article appeared, the co-founders had pivoted to soliciting gift ideas from the general public, in a crude and ultimately doomed attempt to harvest content without that dopamine reward; the “like” button was not yet even so much as a glint in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye. But in the bright early days, when they still had seed money to burn, our intrepid former HP execs hired a bunch of intellectual ne’er-do-wells to come up with gift categories and generate the first few hundred gift ideas. In the absence of as-yet undeveloped algorithmic software capable of weighting the purchasing preferences of desirable demographics, Manvinder and Darrell turned to a motley crew of humanities PhDs, theater folk, and poets. We, in other words, were the algorithm.

My immediate supervisor was a Melville scholar; my cubicle-mate was writing a history of anarchism in San Francisco; two of our colleagues were a married couple who ran an avant-garde theater troupe in the East Bay. I worked 15-20 hours per week, brought my Boston terrier to work (he slipped out the front door a few times and the whole company, endearingly, would each time fan out across Palo Alto to look for him; he was always safely returned), goofed off (I remember playing a game in which we competed to see into how many categories we could fit “Hot Air Balloon Ride”), and wondered if the stock options I’d been promised might make me rich.

The wheels were already coming off the bus by the time Manvinder and Darrell let us go. Maybe they’d never been stuck on too firmly to begin with. “As Saraon looks to his company's future, he is confident that the company will flourish. ‘There are many challenges to ride this negative business environment,’ Saraon said. But ‘I've been around a long time and we have a sensible business plan, a product.’"

Pilot your browser to Surprise.com today and you’ll find yourself at the website of some kind of mobile games app: not a Francophile or a fog machine or a pair of night-vision goggles in sight. While I and my fellow clods worked there, it felt like a little utopia, a bubble within the bubble, a rising tide that made possible for a little cluster of humanists to make rent while making the new frontier a more human and hunorous place. But the tide was sinking even then.

Though the guy does come across to me these days as an unsavory synthesis of Urizen and Orc. Fiery the angels fell, etc.