The late James Caan had three great roles in his career, the first of which eclipsed nearly everything else he did: Sonny Corleone in The Godfather (1972), a compulsive gambler in The Gambler (1974), and the consummate burglar in Michael Mann’s feature film debut, Thief (1981). It was Sonny that turned the Jewish Caan Italian, at least in the popular imagination; it was Sonny’s virility, charisma, rage, and not least, his spectacular downfall at that New Jersey tollbooth that turned Caan into an icon that somehow survived the many dubious choices and wrong turns his career took thereafter. In what I hope will become an occasional series on the theme of men on film, here’s a look at The Gambler, directed by Karl Reisz. (The less said about the 2014 remake starring Marky Mark, the better.)

Caan is cast both with and against type as Axel Freed, a Harvard-educated child of privilege who makes his living as a literature professor at City College in New York. Against type because Caan is nobody’s idea of an intellectual, and he radiates the thwarted energy of his working-class background (his father, a Jewish immigrant from Germany, was a kosher meat-wholesaler and butcher—“a middleman,” Caan once said, “humping sides of meat from trucks to restaurants…. I learned things about respect and loyalty”). With type because Caan’s character in the film is defined by his ultimately self-directed aggression—his impulse to hurl himself at solid walls, praying for something to break—his luck, his body, the self he’s unable to accept.

When the film begins, Axel is $44,000 in debt (that’s a cool quarter million dollars in today’s money) after an epic night of gambling in a sordid apartment. “I never seen such bad cards in my life,” marvels his bookie and only friend, Hips (the irreplaceable Paul Sorvino). Axel heads to work, though not before stopping to lose what might be his last $20 in a pickup basketball game with some Black kids he sees in a desolate court. His work, we might be surprised to discover, is teaching Dostoyevsky and Thoreau to college students, and it quickly becomes clear that his readings of texts like William Carlos Williams’ In the American Grain (I just about shouted when I saw him waving the New Directions paperbook around) are profoundly personal—intellectual justifications for his own craving for risk, for the power of will to master reality so that, should he will it, two plus two will equal five. His most skeptical student is Spencer, a young Black basketball player whose experience of reality, it’s implied, is far stickier and more persuasive than that of the privileged Axel.

We see just how privileged Axel is at a birthday party for his wealthy 80-year-old grandfather, A.R. Lowenthal; in his speech Axel describes his awe and admiration for a man who came from nothing and who was entirely ruthless in his will to build a furniture-store empire—”he stabbed a Cossack pig when he was thirteen,” Axel boasts, for threatening his mother. Lowenthal, for his part, celebrates his grandson’s distance from such squalor, embarrassing Axel by describing him to the company as “the distinguished professor of literature, and future author of great works.” Later, he attempts to persuade Axel to break things off with his gorgeous blonde shiksa of a girlfriend, Billie (Lauren Hutton, who does her best with an underwritten part): “she is not for you! Not for a Jew, not for a scholar.” It’s probably not a coincidence that this scene is immediately followed by one in which Axel menaces Billie with his reckless driving. He then compulsively bets the $45,000 his physician mother gave him in hopes of saving him from having his legs broken or worse, on a trio of basketball games.

Axel’s intellectual pretensions are shared, I suspect, by his creator, James Toback, who’s made a career investigating (and by all reports, embodying) what we’ve learned to call toxic masculinity. The film is in fact autobiographical—Toback went to Harvard, taught at City College for a semester or two, and had a serious gambling problem. But let’s take Toback-Freed’s pretensions seriously for a moment. His quest is Thoreauvian—”to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” Axel’s Walden Pond is the ethnic underworld of Italian wiseguys and Black hustlers—a realm all too familiar to his grandfather but by the 1970s no longer native ground for American Jews. As the film progresses, and as Axel makes wilder, more desperate, more arbitrary moves—particularly toward the end, when he corrupts Spencer to throw a basketball game and then seeks to punish himself by taunting a knife-wielding pimp—he seems more like Ahab in his thirst for some bottom reality. Many of Axel’s exchanges with his bewildered intimates—Billie, Hips, his mother and grandfather—ring of this crucial exchange between the mild-mannered conventional Starbuck and his monomaniacal captain:

“Vengeance on a dumb brute!” cried Starbuck, “that simply smote thee from blindest instinct! Madness! To be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous.”

“Hark ye yet again—the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event—in the living act, the undoubted deed—there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough. He tasks me; he heaps me; I see in him outrageous strength, with an inscrutable malice sinewing it. That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate; and be the white whale agent, or be the white whale principal, I will wreak that hate upon him. Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I’d strike the sun if it insulted me.

The exchange reminds me of one Axel has with his bookie:

HIPS: Listen, I'm gonna tell you something I never told a customer before. Personally, I never made a bet in my life. You know why? Because I've observed firsthand what with seeing the different kinds of people that are addicted to gambling; what we would call degenerates. I've noticed there's one thing that makes all of them the same. You know what that is?

AXEL: Yes. They’re all looking to lose.

HIPS (incredulous): You mean you know that?

Axel and Ahab might as well have “Born to Lose” tattooed across their foreheads. Axel is obsessed with pushing his luck, as in a remarkable moment at a Vegas blackjack table when he doubles down on eighteen with the dealer showing a face card. “You’re crazy,” Billie tells him, to which he rejoins: “Blessed.” Then he tells the dealer “Gimme the three”—and the dealer does. Only in such moments can Axel feel alive, real, having freely (the character’s last name is “Freed”) confronted the “inscrutable malice” of the world and evaded the consequences.

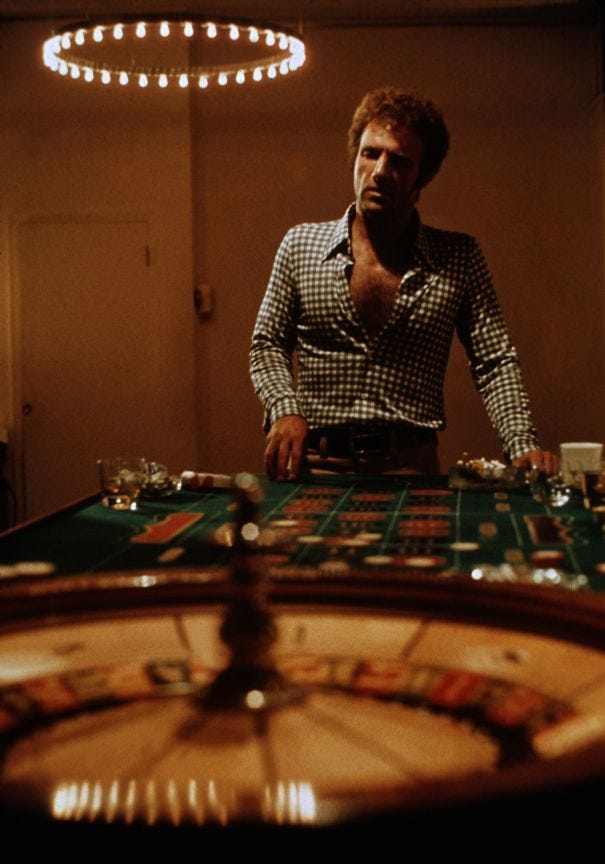

You will notice in these stills how often Axel, gambling, is shot with a halo over or near his head, reinforcing his conflation of secular luck with something like a state of grace. He is like the speaker of Baudelaire’s prose poem “Lost Halo” (my translation):

— What are you doing here, my friend, in this terrible place? You, the drinker of quintessences, you, whose diet is ambrosia. It astonishes me to see you here.

— My friend, you know my terror of horses and carriages. Just now I was running across the boulevard, and as I scampered through the mud, through the chaos of traffic threatening death at every moment, my halo slipped from my head and onto the filthy pavement. I didn’t have the courage to stop and pick it up; I thought it better to lose my badges than to break my bones. And then I said to myself, Misfortune has its uses. Now I can walk around incognito, doing the basest deeds, and turn scoundrel like any mere mortal. And so now you see me here, just like you!

— You should at least advertise for your lost halo, or report it stolen.

— Goodness, no! I feel good here—you’re the only one to recognize me. Anyway, dignity bores me. It tickles me to think that some bad poet will scoop up my halo and wear it shamelessly. To make another happy, what a pleasure—and to make me laugh in the bargain. Think of X, or Z, eh? How funny that will be!

In one of the film’s most disturbing scenes, Axel busts into his girlfriend’s apartment and throws her up against the wall, shaking her like a pinball machine on tilt. His misogyny has been on display throughout the film—Axel treats Billie with the same mixture of amusement and contempt with which the film’s pimps and wiseguys treat him. But only in this scene does the contempt break into brutality. Billie resists him passively, going limp, turning her blue eyes into a mirror to show Axel how far he’s fallen. And the film’s enigmatic final shot shows Axel confronting his bloody face in the mirror—a face slashed and scarred by a prostitute. His expression is triumphant, as one who did in fact “strike through the mask”—the mask of his own face.

Misogyny is the flip-side of masculinity: the terror men feel for their own fragility, which can lead them to disavow every gentle part of themselves. Is the Axel we see in that final shot any closer to accepting his human limitations and his gentleness? Or does he bear now the mark of Cain, the murdered brother being himself?

In an interview, Caan once said that he wished his own children could have learned the lessons he did growing up rough and tumble—a curious replication of the position of A.L. Rosenthal vis-a-vis his grandson, except that Rosenthal is delighted by his grandson’s distance from the streets and appalled by his reckless nostalgie de la boue. Axel is the avatar of the dreams of the Ashkenazi Jews who emigrated to the United States at the turn of the century and worked their fingers to the bone so that their grandchildren might be scholars rather than trombeniks. Rosenthal himself is something of an intellectual manqué—he quotes Whitman to Billie and at one point is seen asleep with a volume of Bertrand Russell’s open on his chest. “I dealt with vipers because I had to,” he tells Axel, “not because I wanted to!” He can’t understand Axel’s atavistic desire to somehow relive his grandfather’s life, any more than Axel can believe that his literary or academic achievements suffice for an identity of which he can be proud.

I recognize in this dynamic something of my own situation. My grandfather (100 years old and going strong) refers to me in delighted tones as “the Professor!” whenever he sees me, though he has neither read Bertrand Russell nor did he build a business empire (he was a salesman, a more successful Willy Loman). Somehow I can never accept his praise; I know or believe on some level that the only kind of success he considers real is business success. This shouldn’t affect me as much as it does, I tell myself. My late father was also proud of my academic and literary achievements, but always seemed slightly bemused by them—though I was deeply touched when, late in his life, he read a novel of mine and loved it in an unreserved way, without the tentativeness of his praise for my poetry.

I’m not a gambler or a thrill-seeker or a misogynist, but I recognize Axel Freed, just as I recognize James Caan as an actor who had the ability to illustrate the dilemma of masculinity so vividly; godspeed, sir. In middle age it seems I am still searching, here and elsewhere, for what it means to be a man.

Your periodic reminder that I’ve published a number of books that you can purchase and read and tell people about. I’d especially appreciate a review—if you’d like a review copy of my new novel How Long Is Now, contact me and I’ll make sure you receive one.