“Kililck! Killick, there!”

That’s how Jack Aubrey calls for his “cross-grained bastard” of a steward, the perfectly named Preserved Killick, when he wants a bit of toasted cheese or a cup of coffee. “What now?” is Killick’s aggrieved, automatic reply. He’s angry because he anticipates his captain’s demand that, rather than jealously hoard the captain’s goods—his wine, his weapons, his uniforms—he must make them available for use. A passage from HMS Surprise describes him with wonderful economy:

Jack had known Killick ever since his first command, and as he had risen in rank so Killick’s sullen independence had increased; he was angrier than usual now because Jack had wrecked his number three uniform and lost one of his gloves: ‘Coat torn in five places – cutlash slash in the forearm which how can I ever darn that? Bullet ’ole all singed, never get the powder-marks out. Breeches all a-hoo, and all this nasty blood everywhere, like you’d been a-wallowing in a lay-stall, sir. What Miss would say, I don’t know, sir. God strike me blind. Epaulette ’acked, fair ’acked to pieces. (Jesus, what a life.)’

A killick is a small anchor, which well describes both his ornery nature and his utility as a character—one of the many minor yet impeccably sketched characters verging on caricature that give the series its nigh-Dickensian life. I’m looking for my own anchor to help me navigate the perilous gap between literature and storytelling that O’Brian so ably traverses.

When I teach fiction writing using Janet Burroway’s classic text, now in its tenth edition, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft, I am always brought up short by a passage from the chapter “The Tower and the Net: Plot and Structure.” It’s worth quoting at some length:

What makes you want to write?

It seems likely that the earliest storytellers—in the tent or the harem, around the campfire or on the Viking ship—made themselves popular by distracting their listeners from a dull or dangerous evening with heroic exploits and a skill at creating suspense: What happened next? And after that? And then what happened?

Natural storytellers are still around, and a few of them are very rich. Some are on the best-seller list; more are in television and film. But it’s probable that your impulse to write has little to do with the desire or the skill to work out a plot. On the contrary, you want to write because you are a sensitive observer. You have something to say that does not answer the question What happened next? You share with most—and the best—contemporary fiction writers a sense of the injustice, the absurdity, and the beauty of the world; and you want to register your protest, your laughter, and your affirmation.

Yet readers still want to wonder what happened next, and unless you make them wonder, they will not turn the page. You must master plot, because no matter how profound or illuminating your vision of the world may be, you cannot convey it to those who do not read you.

My first reaction? Picture, if you will, Stephen Maturin turning to the camera to say in his iciest tones, “You, madam, do not know me at all.”

But of course she does know me. I feel very uncomfortably seen. So do many of my students. Of course we came to writing as “sensitive observers,” aroused and wounded by life, straining after the ideal image or apercu in which our perceptions might be crystallized. That’s why I was and am a poet; that’s why for many years, as a reader, I openly disdained plot (my first novel includes the plaintive line, “Why do we insist upon a plot for our lives?”) for what I saw as its artificial and belabored imposition of order upon experience. Or we might say that I preferred the more overt artifice of poetry—saw metaphor and meter as somehow more honest and authentic to the act of arranging the buzzing, blooming confusion of consciousness into something that might inform a reader.1 A poem does not pretend to the “naturalness” of story, or so I believed, and when I wrote that first novel, I thought of myself as writing poetry in another shape, sentence- rather than line-based. I was chagrined, then delighted, as a plot began to assert itself. Soon I warmed to the art of the storyteller, and it’s the art I’ve been most interested in improving ever since.

The Burroway passage nags. It implies that plot is nothing more than bait for the fiction writer’s hook, the spoonful of eventful sugar to help the medicine of observations go down. Janet Burroway seems to be made more than a little weary by the imposition of plot as something external to her native impulse as a writer. And there’s more than a hint of jealous dismissal in the way she speaks of “natural storytellers.”

The greatest novels, I think, do not resist or elude the demand for plot—they use plot to think, to debate in the dialogical sense described by Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian formalist critic for whom Dostoyevsky is the paramount novelist. For Bakhtin, the Dostoeyvskyan dialogical novel evades the monologism of other forms of knowledge (such as the treatise, the biography, the lab report, etc.) through the creation of characters who are “not only objects of authorial discourse, but also subjects of their own directly signifying discourse.” This seems akin to the experience many fiction writers report of their characters manifesting wills of their own on the page (and counter to Vladimir Nabokov’s dismissal of this form of romanticism: “My characters are galley slaves”). The truth of a novel like The Brothers Karamazov emerges not from Dostyoevysky’s own rather tendentious views on Christianity, but from the fierce and unfinalizable debate between characters like the compassionate would-be monk Alyosha and his righteously inflamed atheist brother Ivan. Dostoyevsky is too brilliant and searching an author to put his thumb on the scale and give Ivan weak arguments; on the contrary, he gives him “The Grand Inquisitor,” one of the most scathing and unforgettable indictments of religion ever written. (Dostoyevsky called it “a poem.”) But this poem does not refute or destroy Alyosha’s faith, rooted as it is in love—for his brother, most of all.

The very greatest novels use their plots as a kind of string upon which to hang pearls of digression. Moby-Dick comes immediately to mind, but also Ulysses and Proust’s Recherche. And we might very well say the same of the Aubrey-Maturin series, a roman fleuve which, by the ingenious device of dual protagonists, generates an astonishing quantity of pearls: sensitive observations by the score of manners, of botany, of anatomy, of prosody, of geography, of sexuality, of friendship, of music. As is abundantly clear from the chapter-by-chapter essays I’ve produced, I am much more invested in Stephen Maturin’s story than in Jack’s, though by all rights Jack is the protagonist and Stephen his sidekick. But Jack is necessary to Stephen—they complete each other. Their alternating points of view are like two braided threads, rugged enough to support chapter-length digressions, such as Stephen’s adventures with Dil and Diana in the seventh chapter of H.M.S. Surprise—probably my single favorite chapter in the entire series, the funniest and the most heartbreaking. There are innumerable forms and styles of discourse strung on Jack and Stephen’s braid: letters, diary entries, lectures, the observations of naturalists, table talk, literary criticism, songs, confessions, drunken disquisitions, ships’ logs—I could go on. It’s a most lifelike profusion, which can make the novels seem like a fully realized, self-sufficient world, like the Surprise herself.

But the Surprise needs a war to inspire her movements, as the sensitive observer needs plot to keep the reader turning pages. And there are no doubt many people who read these novels for the plot, or at least for the battles—for me the least interesting part (which is not to say that they’re uninteresting—I speak of a scale of the books’ attractions, putting the battles on the lower end of the scale and the humor and pathos of Stephen’s pursuit of love and friendship at the top. No doubt one can read O’Brian as the dialogical variety of great novelist as well, with Jack and Stephen representing commitments to the active and the contemplative life, respectively, each man organized around a lack which cannot be entirely filled by promotion in the first case and romance (for a cause, for a woman, for nature itself) in the second. Each character challenges the other at times, politically, intellectually, musically, even sexually (and of course, as in the called-off duel of Post Captain, physically and literally). Peter Weir’s film cannot hope to capture this novelistic quality—it remains a tantalizing sketch for what a cinematic version of the Aubrey-Maturin story might look like if fully treated—but we do get one of the characters’ signature debates, with Jack speaking for tradition and discipline and Stephen speaking for liberty and self-determination:

“Men must be governed,” harumphs Jack. “You’ve come to the wrong shop for anarchy, brother.” Thus Jack asserts the storyteller’s prerogative, the reader’s demand for action and the rejection of modernist plotlessness. “I’m rather understanding of mutiny,” Stephen mutters in reply, and the old Jacobin flashes in him when he denounces “misery and oppression.” This is the meat and drink of the adventure story, of course—of any story. (All happy families are alike, says Tolstoy—and thus not worth reading about. Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own particular way—and we sigh happily and start turning the pages, immersed in story. (Though Tolstoy is unquestionably great, to judge by the immense Levin subplot that any narrative-centric adaptor of Anna Karenina is probably tempted to cut.)

We return by this circuitous path to Preserved Killick, whose name speaks not only to an anchorage—the arrest of forward movement—but to the desire to preserve and conserve. As such is an observer, always spying on what goes on the great cabin, and the most eager and nearly reliable purveyor of rumor on the ship. He is a hoarder of things precious and trivial—he will lovingly polish Jack’s silver plate from now till doomsday, but protests angrily when called upon to us it to serve food. “What now?” is Killick’s cranky, sensitive response to the imperious demand for story. Unlike Stephen in the clip above, he will never openly defy his captain, yet he makes his sensitive recalcitrant displeasure plain, and Jack wisely allows for it. Without such licensed rebellion against the tyranny of plot we’d be reading C.S. Forrester’s fine but one-dimensional Hornblower novels instead of the gorgeous, baroque, funny, and completely immersive wooden world conjured by O’Brian.

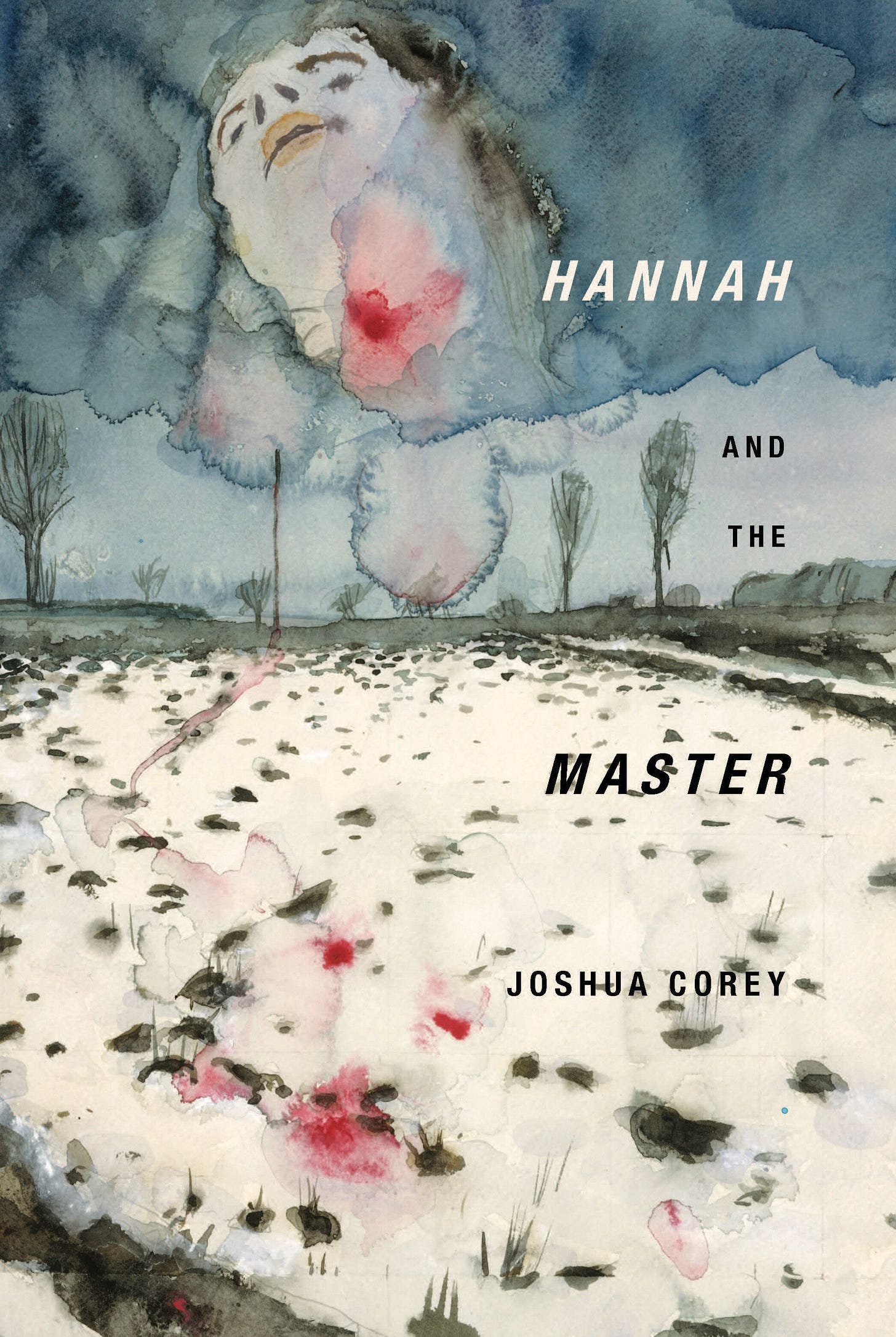

In my own work I’m trying to figure out the right ratio of plot to observation, digression to story. As I said, my first novel Beautiful Soul accretes story almost in spite of itself. My second novel, How Long Is Now, is almost entirely digressive—I’ve sometimes called it a shaggy dog story about grief. By contrast, the three science fiction novels I’ve yet to publish are story-oriented, pacey and propulsive—yet it’s the digressions in them that I love the most. What I love about novel writing is how it creates opportunities for digression—the novel I’m writing is a kind of framework or mirror that captures and shapes whatever interests me at the moment. For my novel-in-progress I’m trying to strike just the right balance between polishing the shiny objects it brings into my reach (Al Capone, J. Edgar Hoover, Jewish boxers, the Battle of Guadalcanal, William S. Burroughs, strip clubs, Chicago, and the JFK assassination) and the imperatives of story. You can’t go on polishing the silver forever, I’ve discovered. Sooner or later you must lay out for your readers the best damn feast you can provide.

It’s late in the year, and I may not get another chance to plug my various attempts at navigating the competing demands of poetry and fiction, digression and story. And I know you’re stumped about what to purchase your friends and loved ones for the holidays!

If you want to do me a solid, you’ll purchase one of my books. If you really want to do me a solid, you’ll review one of them on Amazon or Goodreads:

Inform in the sense of its root: to shape or fashion.