Making Waves with Lynda Barry, Richard Linklater, and Jean-Luc Godard

A day with the Near-Sighted Monkey and friends

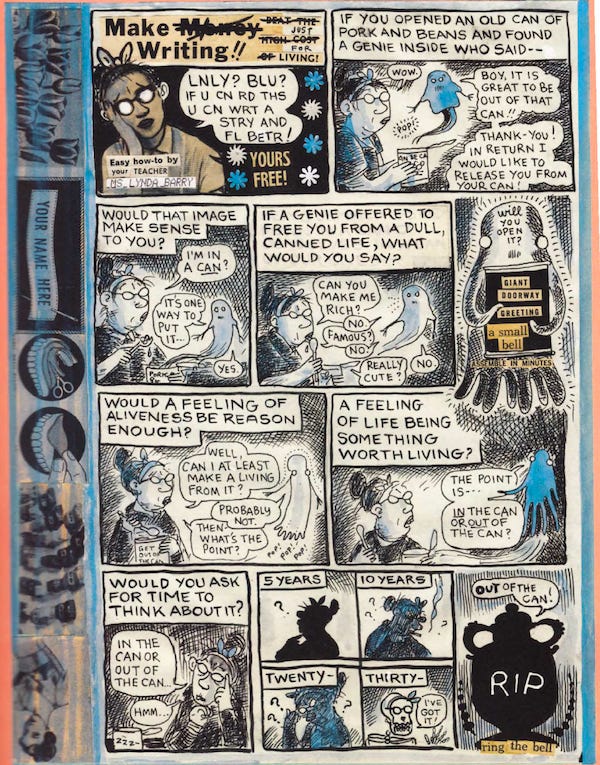

For the past half-dozen years I’ve been using Lynda Barry’s “Writing the Unthinkable” pedagogy in my creative writing courses, with great success.1 Her book What It Is teaches its readers to recover the creativity they unselfconsciously enjoyed as children, a creativity that most people lose touch with.2 Sooner or later, we get funneled into one of two identities: artist or non-artist. I see it all the time in my introductory course, full of non-majors who shrug and say, “I’m just not creative.” Teachers and parents have said this to them until they’ve started to believe it, a process amplified maybe by the slop-charged zeitgeist that wants to outsource creativity to AI. It’s not so much that art is placed out of reach; increasingly, it doesn’t occur to most people to reach for it in the first place.

Yet these folks, the non-majors and non-artists, often get more out of my course than the English majors do. The latter bring a ton of preconceptions to the table, filtered through ambitions too inchoate to realize. There’s a certain species of creative writing student who comes to my classroom having already written a novel or two; maybe they’ve even self-published it on Amazon or Tumblr. But their preoccupation with product and with what a finished work might do for the writer and their self-image is at best premature. There are plenty of problems with the old gatekeepers who used to watch over the publishing process like unappeasable dragons, but they did at least ensure that most young writers had to develop their chops over a period of years, maybe decades, before being published. That period is crucial for developing one’s practice as a writer. Like a yoga practice, you do it because it frees up energy and makes you more flexible, not because it will make people admire you. It’s a tool for living, not an end in itself. Or so I have come to believe.

Whether or not you have talent, whether or not you come to class identifying as a writer or an artist, sooner or later you will be confronted by what Barry calls “The Two Questions”: Is this any good? Does this suck? Caught in their pincers, you are apt to get tight, to overthink, to procrastinate, or not to write at all.

For Barry, writing is a form of drawing, and vice-versa. I love to write by hand: give me an unruled notebook and my trusty Pilot fountain pen and I’m a happy man. But I don’t think of myself as someone who can draw. My daughter, for whom I’ve doodled various characters over the years, disagrees.3 It was in that spirit of disagreement that the two of us drove up to Madison last weekend to attend a “Comix Lab” taught by Lynda and another cartoonist, John Porcellino. There were about forty students, ranging from my daughter’s age to elderly, most of them hipsters or hippies, with a lot of tattoos and ironic T-shirts in evidence. We shared a table with Jacob, a poet and school librarian; Rebecca, an essayist and teacher; and Cris, a multimedia artist and part-owner of Lion’s Tooth, a bookstore cafe and art space in Milwaukee. Really nice folks. Lynda got our attention by singing a song—some sort of doo wop?—and we got to work.

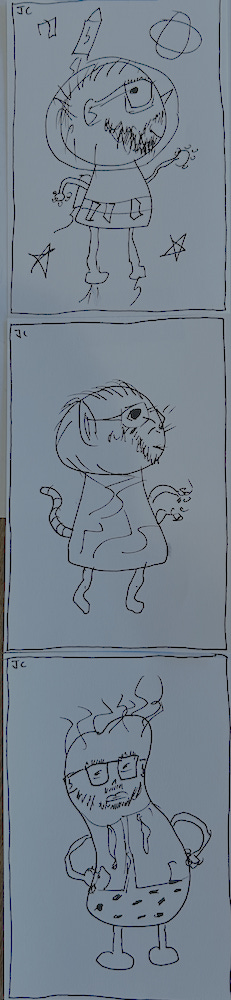

We began by drawing Ivan Brunetti-style portraits of ourselves on index cards as an astronaut, an animal, and a fruit or vegetable:

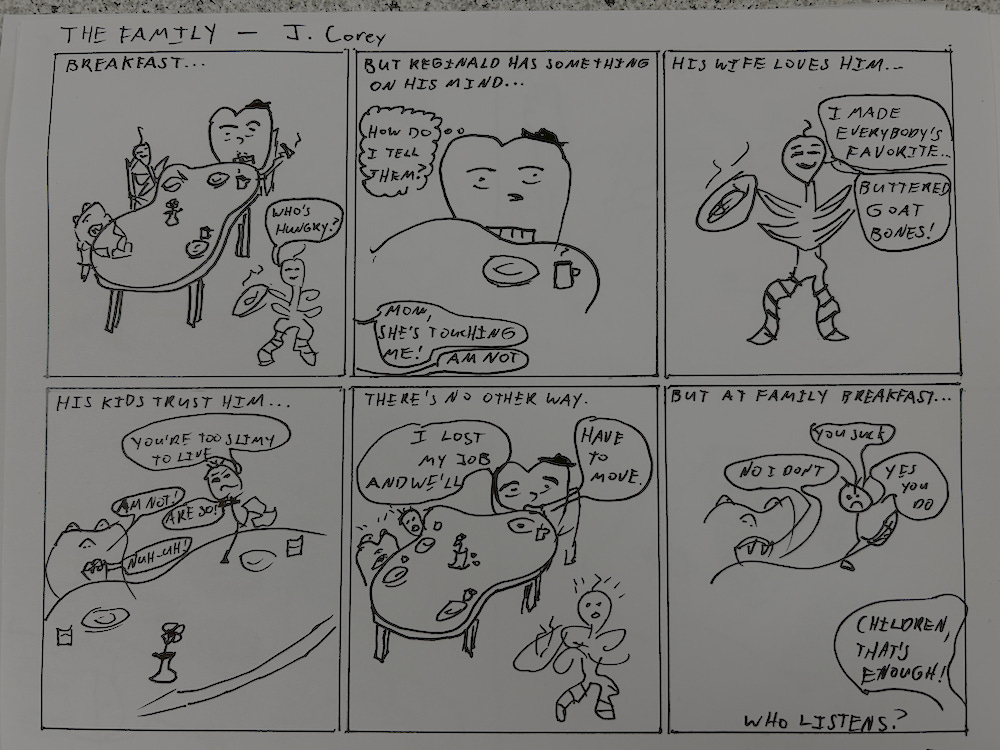

Later, we passed around sheets of paper folded into fours, turning random squiggles into monsters. Here’s what one of those looked like:

We then had to decide which of two monsters were siblings, give them names, then imagine what their parents looked like. Finally we were asked to depict them at breakfast. I did my best:

But the point, of course, was not to produce a masterpiece, or even a monsterpiece. The point is to play with the uncanny power of pen and paper to create something that takes on life. Think about the great characters, Lynda said, like Dracula or Charlie Brown. Where are they? They are not contained by any one drawing or any one book, or movie, or actor, etcetera. But they exist. They feel as real to us as members of our own families.

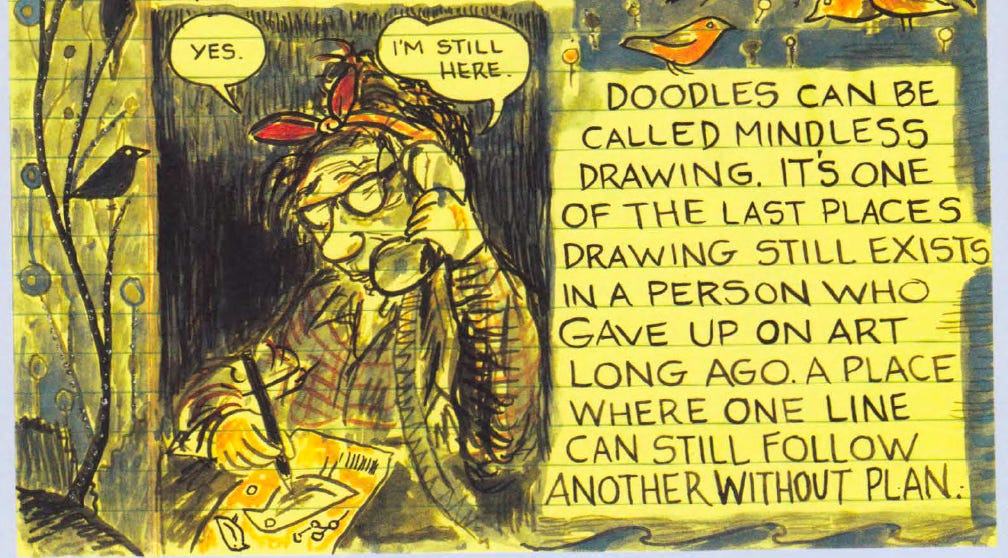

For Lynda Barry, drawing and writing are most alive when we can approach them “without plan”; her workshops are designed to cultivate the spontaneity that gets beaten out of most people as they get older. Ray Bradbury once said in an interview that when he was at the typewriter, he wasn’t thinking, but living. Lynda would certainly agree.

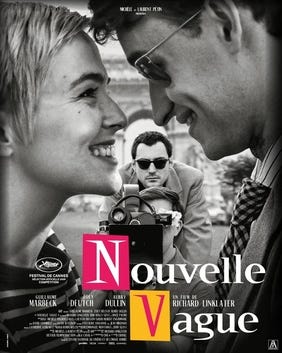

I found myself thinking about the workshop last night while watching the second of the two films Richard Linklater has made and released simultaneously, both of them about significant twentieth-century popular artists. The first, Blue Moon, I’ve already written about. The second is Nouvelle Vague and it’s very different in style and spirit. It follows Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) and his not always merry band of pranksters as they run around Paris filming Breathless, the 1960 movie that synthesized the French New Wave with the crime thriller, captivating (and creating) cineastes forever afterward. Though it’s shot en français, in black and white, complete with cue marks, and in the same aspect ratio as the original film, it doesn’t attempt to imitate Godard’s style—there are no jump cuts, though we see Godard instructing a disapproving Cécile Decugis to put them into Breathless itself. The focus is not on what Godard sees through his camera (his cameraman repeatedly offers Godard peeks through the viewfinder to see what a shot will look like, but Godard always declines) but on how the film’s crew, actors, and beleaguered producer (a very funny Bruno Dreyfürst) see Godard. Marbeck, who never removes his sunglasses, plays him as a kind of hyperactive imp, perpetually quoting other artists, filmmakers, and philosophers while throwing low-key tantrums or calling a wrap after just two hours of filming because “I’m out of ideas.” At one point we see him walking on his hands at a party, a perfect image for the seemingly improvised, upside-down approach of French New Wave cinema.

Over the course of Nouvelle Vague we watch Godard continually violate the basic rules of narrative filmmaking. Not only is he working without a script but he doesn’t give a damn about continuity (“Continuity,” he intones excitedly, “is not reality”) or consistent sight lines. His decision not to use sync sound frees him to talk to, or at, the actors, supplying them lines or just suggestions for lines that will be dubbed in later on. For street scenes he folds his cameraman, Raoul Coutard (Matthieu Penchinat) into a delivery wagon, turning the citizens of Paris into unpaid extras, and trundles him after Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) and Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) as they stroll down the Champs Élysées improvising dialogue. Seberg mostly complains about Godard’s unorthodox methods even as she flirts with Belmondo, to the increasing displeasure of her husband François Moreuil (Paolo Luka Noé).4

Seberg, a professional, knows how arduous movie-making is supposed to be, how much planning is usually involved. She is wary of Godard’s freaks after suffering considerable ill treatment at the hands of the legendary director Otto Preminger, who cast her as the lead of his misbegotten Saint Joan (1957). The film was widely considered to be a disaster, and Seberg’s performance was singled out for scorn. Now she’s in the hands of a new, untried director whose studied innocence starkly contrasts with the deep experience of Preminger, but she finds the change far from reassuring. Everyone who meets Godard, one of the leading critics of Cahiers de Cinema, can see that he is some kind of genius. But can the intellectual genius of the critic translate into the practical genius needed to make a great film?

Seberg is terrified, as Belmondo is amused, by the fact that Godard doesn’t seem to know what he is doing. In that he is like Lynda Barry in her pedagogical persona as the Near-Sighted Monkey; to be an artist, particularly an artist with an analytical bent, requires the left hand not to know what the right hand is doing. Or we might say, the left brain and the right brain. Barry has been strongly influenced in her thinking by Iain Gilchrist’s great and provocative book The Master and His Emissary, a speculative work of neuroscience arguing that our culture has been dominated, to its detriment, by the analytical left brain over the more holistic and intuitive right brain. I’m not a neuroscientist, so I don’t know if this is true, but it’s a useful metaphor. To be an artist, you have to find some means of distracting the critical, analytical mind so as to access what your intuitive mind has to offer. It’s the intuitive mind where we find the image—a concept absolutely central to Barry’s practice as writer-artist, and to Godard’s as well.

As I watched Nouvelle Vague I became increasingly fascinated by Godard’s refusal to look through the viewfinder. He becomes an utterly paradoxical figure, an aleatory control freak, so trusting of his own artistic intuition that he can use his collaborators to their absolute fullest, as though they were extensions of his own senses. Even the scene in the editing bay at the end doesn’t show Godard editing, but communicating his wishes to his (female) editors, who are instructed to ignore continuity and to include only those shots that are alive. It shouldn’t work, but it does work. Godard, the critic, knows enough about the rules of filmmaking to forget those rules, to put them aside. The camera, actors, crew, and the streets of Paris become instruments and extensions of his imagination. And he has accomplished something even more extraordinary: his critical brain, the powers of which he honed so finely in his years at Cahiers de Cinema, is in the service of his artistic brain, rather than vice-versa.

That’s what I find so extraordinary about these artists—Barry, Godard, and Linklater. They have so much to teach the beginning artist, filmmaker, or writer! They in fact teach beginning itself—what the Zen teachers call beginner’s mind. And it’s something that even experienced artists, even grumpy middle-aged artists like me, must continually relearn.

During the workshop Lynda described her pedagogy as “open source,” which was a great relief to someone who’s been using her ideas for years.

She’s published a remarkable series of books on her teaching techniques, including Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor, Making Comics, and Picture This: The Near-sighted Monkey Book. But What It Is is my favorite.

My daughter draws really well—she’s all-around artistic in a way I’ve never been. But I’m not going to share her work here.

A special shout-out to Zoey Deutch for her performance as Seberg; she captures the actress’s liveliness and gamine appeal but also her concern for her career as she delivers a famous line to an interviewer: “All the publicity in the world will not make you a movie star if you are not also an actress.” Seberg met a tragic end, foreshadowed perhaps by the hints of melancholy that play over Deutch’s face. She also does a fantastic job of moving easily between English and a fluent-sounding, Midwest-accented French.