The three writers under consideration are as nearly well known for not writing as they are for writing, for success in failure and failure in success. Open Kafka’s diaries at random and you are very likely to come across an entry like this one:

7 June 1912. Bad. Wrote nothing today. Tomorrow no time.

Or:

7 February 1915. Complete standstill. Unending torments.

Or how about:

18 September 1917. Tear everything up.

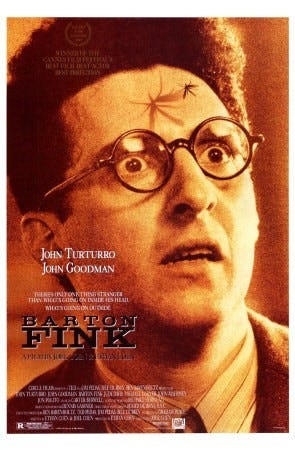

Proust, another neurasthenic assimilated Jew, was considered a sickly dilettante by all who knew him, until he burst out in his forties with the astonishing first volume of À la recherche du temps perdu, forcing the literary elite who had dismissed him (most notoriously André Gide, who turned down Swann’s Way when it was offered to Gallimard for publication) to eat considerable crow. Clifford Odets is a less familiar figure, but popular culture remembers him as the template for the hapless protagonist of Barton Fink, a playwright-turned-screenwriter with a nightmarish case of writers block that the Coen brothers gleefully sketch in shades of the Kafkaesque.1 Odets did indeed flourish briefly as a playwright—in the 1930s he was one of the most famous writers in America—before being lured to Hollywood, which was more or less the death of him as a serious artist.2

Who was Clifford Odets? He is better remembered today in theatrical circles than in literary ones: a founding member of the Group Theater in 1930s New York, he was part of the magic circle that included Lee Strasberg, one of the architects of Method acting. His plays, rooted in the Yiddish-inflected poetry of striving Jewish immigrants, tend to be sprawling affairs, crammed with kitchen-sink lyricism; there’s a direct line from his work to the plays of Arthur Miller, Neil Simon, and David Mamet. I stumbled across Margaret Brenman-Gibson’s biography in a discards cart at the Chicago Psychoanalytic Institute—a signed first edition, no less.3 Brenman-Gibson was a trained psychoanalyst who knew Odets personally; her husband William Gibson, a playwright (no relation to the SF writer) had been one of Odets’ students. When Odets died of stomach cancer in 1963, she took it upon herself not just to write the man’s biography, but to analyze him. The result is one of the strangest, most penetrating, and most compulsively readable biographies that I’ve ever read.

Most biographies have footnotes; Brenman-Gibson’s is unusual for having an entire second set of what amount to clinical notes, in which she goes beyond reporting the narrative impact of a particular moment from Odets’ life and writings into analyzing its psychological significance. One note in particular arrested my attention: a kind of formula or explanation for how Odets found artistic success, or how that success found him:

In the course of this study it has become clear… that some conditions—beyond the indispensable of native talent and a profound, if unconscious, bisexuality—are significantly facilitating for the bringing forth of live young: the presence of an unresolved unconscious conflict with an optimum “openness” of its materials to a pre-conscious level (not under rigidly embattled repression or defensive operation); the choice of a form for the expression of the conflict—and consequent fantasy—which is not too distant from the playwright’s self-identity and which provides a psycho-historical bridge to a social matrix which invites and supports the expression of this form of mastery. (663, emphasis in original)

Passing over for the moment the queasy metaphor of “live young” for successful artworks and the predilection for “profound, if unconscious, bisexuality,” this dense passage offers us a key to the psychology of the kind of successful artist who is always on the brink of unsuccess—whose psychological fragility is part and parcel of his art.4 We can break it down according to the three italicized phrases as A, B, and C:

A - An unresolved unconscious conflict that is not so painful or urgent that the writer can’t experience “openness” to the materials it generates. In other words, the writer is able in some significant way to play with his pain.

B - The choice of form. This has manifold possibilities. Odets hesitated in his early career between acting and writing as the best means of expressing his inner turmoil; later, fatefully, he made the move from playwriting to screenwriting.

C - A “social matrix which invites and supports the expression of this form of mastery.” This means there’s an audience for what the artist is doing, though in Odets’ case it may also refer to the matrix (which you’ll remember derives from the Latin mater, “mother”) of the Group Theater which was his artistic home during his most fruitful period. Also, Brenman-Gibson seems to mean “mastery” in the psychological sense—though from her perspective there may be no meaningful distance between an artist’s psychological mastery of his unresolved unconscious conflict and his mastery of artistic form.5

Any biography, let alone a psychoanalytic biography, will devote most of its pages to the exploration of A: Odets’ circumstances as the son of a crass, self-centered Jewish immigrant whose ham-handed quest for bourgeois respectability led him first to terrorize and later to exploit his sensitive son. His gentle but remote mother, meanwhile, was trapped in a loveless marriage and occasionally suicidal, frequently musing that she’d be better off dead. “Hapless and helpless,” Odets wrote in a letter to his biographer the year before he died, “the Jewish prophet is being eaten alive by the Jewish father in me; and if somewhere it doesn’t stop soon, I shall be indeed dead.” Odets struggled all his life to square that particular circle: the desire to explore his inner world is constantly thwarted by his father’s need to play the part of the big man, and vice-versa.6

When the Depression hit, something miraculous occurred: C came into alignment with A, as the literal hunger of America came into phase with Odets’ emotional and spiritual hunger. Meanwhile the form of the Broadway play, which in the 1930s had a claim to cultural centrality unimaginable today, proved to be the medium in which Odets was able to use himself to create fictions by which the age seemed to discover its meaning and purpose. Not the least of the painful ironies of his career is how Odets tried to “universalize” himself after his initial success, moving away from the specifically Jewish lower-class milieu in which he’d been formed toward more “American” characters, or at least less Jewish ones. By so doing, he cut himself off from the resources delivered by A—or to put it another way, internalized antisemitism drove him into the arms of psychological mastery and away from an artistic mastery rooted in essential experience. We’ve all witnessed artists who, having spontaneously caught the mood of their times, deform themselves in self-conscious pursuit of their audience (C) after that mood has passed. That seems to have been what happened to Odets, whose change of form (B) from stage to screen meant that he’d always have plenty of money but that he would never again sing from the culture’s heart the way he did in the Thirties.

Unlike Odets, Kafka was not the son of immigrants, but he was an assimilated Jew whose assimilation was more imperfect than most due both to historical circumstances (a German-speaking Jew in Austro-Hungarian Prague was alien both to the Germans who held the power and the Czechs who held the majority) and temperament. His frightening father Hermann was similar to Odets’ father Louis in many respects: a crass, bullying, self-dramatizing petit bourgeois, for whom the business of life was too serious for art and culture to get a look-in. Julie Kafka proved to be as unsatisfactory a mother to Franz as Pearl Odets was to Clifford: both women were depressive appendages to their domineering husbands, constitutionally unable to deliver the affection craved by their sons. Like Odets, Kafka was trapped between the internalized voice of the father and the voice of his own prophetic soul; his first “indubitable” story, “The Judgment,” takes the fatal confusion of those voices as its subject. He did not find success in his lifetime, but posthumously achieved a global notoriety of which Odets could scarcely have dreamed.7 Let’s try Brenman-Gibson’s schema on him:

A - Kafka was anxious, anorexic, introverted, hypersensitive, and frequently crippled into silence by self-consciousness. Yet his ability to play with the sources of his torment is unmatched.

B - Many books have written about Kafka’s unique mastery of form: the unnaturally honed purity of his German, the austere skill with which he conjures impossible and absurd scenarios whose logic he then follows to the bitter end. But his struggles with form were epic, even existential. Most scholars agree that you only get the full corpus of Kafka if you read the (voluminous) diaries and letters alongside the fiction; these give you the necessary glimpse into the abyss that yawned for Kafka between literature and life. There’s also his struggle to become a novelist—all three of the extant novels, The Man Who Disappeared (aka Amerika), The Trial, and The Castle, went unfinished. He did achieve something like perfection in the shorter pieces that followed “The Judgment,” which he wrote ecstastically in a single night—an experience from which he seemingly never recovered and was always trying to recapture. The price of form, for Kafka, was very nearly everything.

C - There are at least three social matrices to consider when it comes to Kafka’s reception: his family, the cultural milieu of German-speaking Jews, and world literature. His family was a torment to him, and in the end his only real subject. Prague, “the little mother with claws,” was like a macrocosm of that family, unendurable yet inescapable. His existential homelessness was Jewish in character, which led to his flirtations with Zionism and his famous remark to Max Brod about the predicament of German-Jewish writers: “With their back legs they stuck fast to the Judaism of their fathers, and with their front legs they found no new ground.” Posthumously, of course, Kafka is one of us, the prophetic uncle who understood the black fantastic heart of the twentieth century (rational means to irrational ends) decades before anyone else.

As for Proust, biographies may seem redundant given the autobiographical nature of À la recherche du temps perdu. But the autobiographical is not autobiography; in any case, when I pick up a writer’s biography it’s the work I want to know the life of.8 Marcel Proust was baptized Catholic but his mother, whom he loved passionately, remained a Jew all her life, so I have few scruples about claiming him for the tribe to which Kafka and Odets also belong. He was more fortunate than Odets and Kafka in many ways, less fortunate in others. Proust’s family was wealthy and he was petted and fussed over to a degree that would have left the other two writers in my study writhing with envy. But is there so very great a difference between the trauma Brenman-Gibson describes for little Clifford Odets, frozen in his chair waiting for Mommy to return, and the famous scene from Swann’s Way in which young Marcel goes nearly out of his mind with desperation for a goodnight kiss from Maman? Reason not the need, as another man anguishing after a maternal figure’s love once said. All three of the boychiks under consideration were unusually sensitive—to themselves. Proust, like Kafka, was a hypochondriac (Odets also had tendencies in this direction but seems to have had a more naturally robust constitution). But his physical frailty and innumerable foibles shouldn’t distract us from his considerable mental toughness—it took discipline to reshape his environment the way he did and to write the thousands of pages of his Search. Let’s try the formula on him:

A - Once again we have a Jewish boy caught between a worldly, successful father and a sensitive, more artistic mother—though in this case the mother was utterly devoted to her son’s happiness, while the father was not a petty bourgeois businessman but a wealthy, celebrated physician and innovator in the field of public health. But there were other unresolved issues bound up in Proust’s intersectional identities, as the son of a Jew brought to consciousness of antisemitism by the Dreyfus Affair and as a homosexual. Proust seems to have somatized much of this distress in his hypochondria, his day-for-night lifestyle—in this he resembles Kafka more than Odets, but unlike Kafka he never held a job (and Kafka hated his job, but he was remarkably good at it). He was cushioned by wealth in a manner denied to the other two men, but that doesn’t mean he had an easier time finding where he fit in the world. There was no fit, in fact. That’s part of what makes someone an artist.

B - Proust’s search for artistic form can’t be separated from his search for a form of life—once he was done with school (like Kafka he studied law against his will), the army (which he loved, in spite of his physical frailty), and with the most notional possible form of employment (an unpaid librarian who spent his entire term of service on sick leave), there was nothing left to him but an endless round of parties, concerts, spa visits, and the occasional essay or book review. His first book, Pleasures and Days, was a series of feuilletons about which he was faintly embarassed ever after, and it certainly didn’t win him much real respect from other writers. When he hit upon the idea for the Search he was unsure whether he could really call it a novel, and even after it began to be published he fretted over whether others would be willing to accept its development of the theme of time in lieu of an actual plot.9

C - The unusual length and publication history of the Search has become part of its reception. The first volume, Swann’s Way, appeared just before the First World War broke out, and one can easily imagine the appetite for such fiction disappearing along with the rest of European civilization into the trenches. But since Proust was still revising and adding to the novel as it came out in successive volumes, he was able to incorporate the war into the story, as he had incorporated the Dreyfus Affair as a wedge between the two social worlds through which the novel moves—the bourgeois world of Swann and the Verdurins on the one hand, the aristocratic milieu of the Guermantes on the other. The war ended up adding immeasurably to the novel’s pathos and the sense of irrevocable change and loss that makes the ending so incredibly moving. The artistic good fortune of Proust, like that of Kafka and Odets, turns out to be the byproduct of suffering on a global scale.

None of these writers could be deterred from the pursuit of their inner visions. None of them found enduring happiness in love; each in his way was baffled by the otherness of the objects of his desire—Proust was consumed by the jealousy that was one of his greatest subjects, Kafka was unable to imagine a marriage that wouldn’t consume his identity as a writer, Odets was a serial seducer and an impossible husband.

An observation made by Clifford Odets’ mother could as readily have been spoken by the moms of Franz and Marcel: “her son was one of those rare beings whose gift carries with it the rejection of others’ experience, and thus the capacity for fresh sight—a sense of playful wonder conveyed to the rest of us in their works” (27). Are the works of these writers nothing more than the product of wounded narcissism, expressing the desire to write their way back to the breast? Did the greater quantity and quality of affection that Proust absorbed from his mother make it possible for him to write his novel, whereas Kafka left three novels unfinished, and Odets never produced a real masterpiece? Were these guys just a bunch of solipsistic navel-gazers, or what?

Navel-gazer or no, naturally I ask myself what it will take for my newest novel, which I’m currently editing, to succeed. Have I achieved sufficient “mastery” of the unresolved unconscious forces emanating from my Jewish masculinity, my family history, personal traumas, etc., to play with them and so find for them the appropriate artistic form? (It is probably significant that I have tried so many different forms for this story: poems, essays, finally a novel.) And assuming I succeed in giving artistic form to my psychic underground—effectively transforming A into B—will anybody care? Is there a C that will find itself expressed in the work, especially given that my chosen form, the novel, has become peripheral to the culture at large?

Walt Whitman wrote that “The proof of a poet is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” The instrument, or perhaps I should say organ, of a poet’s affection is language. Language is never self-created—it is the social matrix to rule all other social matrices. That’s what saves these writers from self-absorption; that’s why reading their work we feel personally addressed, perfectly adapted to their dreams and their nightmares. (This is still true of Kafka and Proust; in the case of Odets you probably have to be in the audience watching Morris Carnovsky and Stella Adler performing in 1936 to appreciate the full effect. But appreciate it they did!) As William C. Carter puts it, “A creative person is, by definition for Proust, an altruist, someone who learns how to make his egotism useful to others” (565). It’s an uncomfortable but useful definition, from behind which peeks that most indispensable of discredited ideas, the idea of genius.

I make no claims to genius—or to altruism. Yet compulsively I make the experiment of putting A into B, solitary and yet not alone, to wager that C exists,10 and that its affections are being somewhere prepared.11

Really quite surprising that the Brothers Coen have never made a straight-up Kafka adaptation; on the other hand, Barton Fink, A Serious Man, and Inside Llewyn Davis, among other films, show how fully they’ve internalized his perspective.

This account is a little simplistic, as we shall see, but I’m as interested in these writers’ receptions as I am in their actual work—otherwise how are we to understand the loaded terms success and failure in regards to them? Here, apropos of nothing, is Clifford Odets on the cover of Time magazine in 1938:

The caption, if you can’t quite make it out, reads Down with the general fraud! A sentiment I endorse.

The book caught my eye for the thread of connection between Odets and one of the protagonists of TLWOJR, the boxer Barney Ross. In his post-fight career Ross, at loose ends, was cast as the lead in a revival of Golden Boy, Odets’ play about a violinist-turned-boxer, only to beg off when he discovered that taking a punch was easier than acting.

This description applies to 99 percent of writers; the other one percent ought to be ashamed of themselves.

The tension between the desire to master one’s problems in life versus the desire to master them in art is fundamental. I think of the famous last sentence of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle: after six volumes and thousands of pages of struggle with the demon of his unloving father, the narrator turns his attention to his own young family and triumphantly concludes: “Afterwards we will catch the train to Malmö, where we will get in the car and drive back to our house, and the whole way I will revel in, truly revel in, the thought that I am no longer a writer.” Of course this is only a thought, as he has written close to a dozen books since then.

Father and prophet are both masculine, but the latter’s association with Odets’ half-despised religious heritage, and with poetry, genders that self as feminine. This may be where the “profound, if unconscious bisexuality” comes in; I am reminded as well of the torments suffered by Von Humboldt Fleischer, Saul Bellow’s stand-in for Delmore Schwartz, whose identity as a “book Jew” is perpetually compromised by his envy of “money Jews” (I adapt here Ira Glass’s useful shorthand for this dilemma). Like Odets, the talented and photogenic young Schwartz was considered the future of literature for much of the 1930s, but his swing at greatness, the turgid long poem Genesis: Book One, landed like a lead balloon, and he sank into alcoholic unfulfillment. Schwartz’s downfall was much bleaker and more bizarre than Odets’ fitful decline, but he reminds us that the brilliant love-starved boychik is a familiar literary type.

It’s true that the Coens remembered Odets for Barton Fink, but Kafka has become an icon. Look no further than Franz Kafka’s It’s a Wonderful Life, the Oscar-winning short film from 1993 written and directed by Peter Capaldi and starring an absolutely perfect Richard E. Grant as our man:

Which is why I’m intrigued by this new book.

I have been thinking a great deal about the relationship of theme to plot now that The last Words of Jack Ruby has finished its first lap; the plot is complete, but the theme or themes continues to ramify and ripple through my mind, and when I sit down to revise it will be with two related but separate purposes: to clarify any errors in the plot, and to intensify the theme, to reduce it the way you reduce a sauce. Proust’s genius is in the alchemy of plot and theme; he shows that the supersaturation of one elides imperceptibly into the other, when given the space.

More safe I Sing with mortal voice, unchang'd

To hoarce or mute, though fall'n on evil dayes,

On evil dayes though fall'n, and evil tongues;

In darkness, and with dangers compast round,

And solitude; yet not alone, while thou

Visit'st my slumbers Nightly, or when Morn

Purples the East: still govern thou my Song,

Urania, and fit audience find, though few.

But drive farr off the barbarous dissonance

Of Bacchus and his revellers, the Race

Of that wilde Rout that tore the Thracian Bard

In Rhodope, where Woods and Rocks had Eares

To rapture, till the savage clamor dround

Both Harp and Voice; nor could the Muse defend

Her Son. So fail not thou, who thee implores:

For thou are Heav'nlie, shee an emptie dreame.

—John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book VII (1674)

Follow, poet, follow right

To the bottom of the night,

With your unconstraining voice

Still persuade us to rejoice;

With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse,

Sing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress;

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.

—W.H. Auden, “In Memory of W.B. Yeats”

Fun stuff. I love "Barton Fink," but I take its literary portraits/caricatures (of both Odets and Wm. Faulkner) with a grain of salt. As for a Kafka film, there is Stephen Soderbergh's "Kafka," which I didn't much like, but which is legitimately a film about the person Franz Kafka.

This is excellent. That Odets biography is a great find, and this is a truly imaginative and insightful use of it. Let me point out a typo you’ll want to fix: point B under Proust begins “Kafka’s search for artistic form”