The bow-chaser

Which it's the first (or is it the second?) of a series of essays on Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin novels

[This was the first substantive post in the initial project of rereading all twenty of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels and writing an essay about each one. With the launch, as of July 30, 2025, of The Aubrey-Maturin Review, I plan to go through the old essays and make a few additions and revisions as needed. If you are new to the project, this is a good place to start; if you want to move straight on to the first novel, Master and Commander, click here.]

It must have been very near to the time of their author’s death in 2000 that I first began reading what some fans call the Aubreyad—the twenty-book series about Royal Navy Captain “Lucky” Jack Aubrey and his boon companion, the physician/naturalist/spy Stephen Maturin. I can’t recall the exact date I first picked up the first novel in the series, Master and Commander, but it was probably when I was living in California, for I remember using them to while away the transcontinental flights I took every few months to see family in Chicago and New Jersey.1 Twenty years, more or less, a period in which I’ve seen things go from bad to worse in this country—from the hanging chads to 9/11 and the subsequent catastrophic military adventurism, to the 2008 crash that led to Trumpism, to the rapid decline in our prospects for a livable planet. In that same dismal period I’ve led what can only be called a charmed personal life: a graduate education at elite institutions devoted to the reading and writing of poetry with increasing facility and delight; meeting the woman to whom I’ve ben happily married for fifteen years; securing by sheer luck a tenure-track teaching job on the brink of the economic crash, like the Unsinkable Molly Brown; raising my furiously funny and only occasionally deeply exasperating child, who’s about to be b’mitzvahed. Personal happiness against a backdrop of world-historical calamity; perhaps there’s a clue there to the appeal of these novels, and their focus on the generally fortunate progress of two friends even as they are sometimes cruelly battered in the course of the Napoleonic Wars then remaking the known world.

I’ve written about Aubrey and Maturin before: why return to them? Justin E.H. Smith inspired me with his occasional series of essays inspired by his reading of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. Smith begins with an anecdote about Christopher Hitchens, who was supposedly about to embark on a Proust-reading project just before 9/11 sank him into the dogmatic slumbers that afflicted him for the remainder of his reflexively contrarian life. A time of world-historical convulsion offers exactly the right moment in which to read Proust, Smith claims, though not necessarily as “a private indulgence and a retreat from engagement.” Having entered what he calls, tongue at least partly in cheek, “the post-experiential phase of life” (get a grip, Smith! The man is two years younger than I am, and I happen to be the same age Proust was when he died); having, as I do, an appetite for big books and a case of “incurable graphomania,” Proust becomes the scintillant object on which Smith can reflect. There is something retrospective about one’s fifties, a tendency exaggerated in my case by the pandemic, which has for better or worse intensified certain habits of withdrawal. (Though I don’t write in bed, nor have I withdrawn into the shelter of a cork-lined room. At least, not yet.)

I could write about Proust—I finished reading Le Temps Retrouvé (in English, hélas) only last year, more than a decade after first opening Swann’s Way and reading the famous first sentence, in the original C.K. Scott Moncrieff translation: “For a long time I used to go to bed early.” Proust certainly enjoys a higher degree of cultural cachet than O’Brian, and he’s enjoyed it for much longer, having written what many consider to be the supreme achievement in the novel form, a modernist epic of soul-making that serves as a metonym for the best of French culture, if not for culture tout court. O’Brian, by comparison, cranked out twenty volumes of what plausibly could be characterized as a hypertrophied boys’ adventure story, a work of genre fiction that scratches the same itch as the Star Trek novelizations I used to devour while sitting cross-legged on the industrial blue-carpeted floor of my local Waldenbooks.

O’Brian himself read Proust, and sprinkles his novels with references to his work: at one point Aubrey sails quite close to Balbec, the fictional Normandy seaside town where young Marcel meets Albertine; at another point, Stephen Maturin broods over his feelings for his own Albertine, a fierce young woman named Diana Villiers, using the Proustian phrase intermittence du coeur. And O’Brian’s fans, prone to hyperbole, have not been shy about comparing his saga to Proust’s, not to mention the works of Austen, Trollope, Melville, and Conrad. The simplest point of comparison is the baldest: both writers produced a series of volumes that add up to one immensely long novel demanding nothing less from devotion from their readers, at least if one is to have any hope of keeping the immense largely cast of characters straight. They are also challenging on the sentence level, though for slightly different reasons: Proust’s sentences are uncommonly long, periodic creatures in methodical pursuit of minute insights about human behavior, whereas O’Brian’s are saturated with sea-terms that rereadings refuse to clarify; like Stephen Maturin, in spite of twenty years’ at sea I remain perfectly incapable of distinguishing between a sheet and a halyard.

O’Brian is Proustian in other ways: he is just as acute in his (often very funny) analysis of manners and social relations, though he is more often compared to Jane Austen (the second novel in the series, Post Captain, is basically an homage to Austen; imagine if Persuasion followed the sea adventures of Captain Wentworth with the same level of detail as it does the social intrigues of Bath). To borrow again from Justin E.H. Smith, O’Brian is very much concerned with “the way in which social reality imposes itself on us.” That the relations that O’Brian examines are the seemingly archaic ones of early ninteenth-century Britain—and more particularly those experienced aboard the all-male society of an English man-o’-war—do not render them any less rich, or any less useful to a 21st-century reader who wants to better understand how history and class has shaped his own formation. We Americans must look abroad, as Henry James did, if we want to understand class, so successful and all-encompassing is the ideology of democratic individualism that we’ve been freebasing for the past three centuries.

There’s one further objection to taking Patrick O’Brian’s sea stories seriously that doesn’t apply as much to Proust. Proust was a Jew and a homosexual—never mind the richly ambivalent attitude he struck toward both of those identities. His literary and cultural significance has only been magnified by his gayness. O’Brian—a rather mysterious figure, whose birth name was Richard Patrick Russ—was, so far as we know, white and straight (though there was apparently some embarrassment over his affinity for Irishness—an affinity that, in combination with his pen name, led him to being accused of posing as Irish. I relate, weirdly enough, to this—growing up with the deracinated last name Corey, a variation on Cohen, I wondered for a while if I might not somehow be Irish, and Irish literature continues to hold a very special place in my heart. I digress). Anyway, should we not be skeptical of a dead white guy who wrote historical novels that can appear at first blush as retrograde as Kipling in their celebration of colonial war and imperialism? A list of O’Brian’s biggest fans includes a number of right-wing characters, William F. Buckley, Jr., George F. Will, Charlton Heston, and David Mamet among them. Yet I believe that, through a political lens, reading O’Brian becomes even more valuable, even urgent. Whatever the man’s politics (and I should note that the novels, the first of which was published in 1970, demonstrate a great deal of sympathy to its gay and non-white characters, treat their women characters with a surprising degree of nuance, and feature a protagonist, Stephen Maturin, who is a passionate supporter of independence for his two native lands, Ireland and Catalonia), they are refracted by means of literature, and so are more nuanced and sophisticated than 99 percent of the pop culture backwash in which we languish, even and maybe especially that chunk of it that has undergone facelifts to make it more politically correct.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but there is something unambiguously fascistic and illiberal about our popular narrative culture, which in my lifetime has shifted hardly a jot, substantively speaking, from the naive heroism of a Luke Skywalker to the superficially cynical but ultimately just as naive heroism of Tony Stark. We are trapped in an endlessly self-replicating regime dedicated to the ruthless conservation of decades-old intellectual properties, nearly all of which urge us to be suspicious of collective action and to put our faith in (usually white, usually male) supermen. Since I was seven years old, mouth agape at the sight of my first Star Destroyer, I and everyone else have been subjected to the ritually repeated story of a lone hero who must more or less singlehandedly save his city or kingdom or galaxy from a nefarious villain and his conspiracy of henchmen. Whether pure of heart (like Christopher Reeve’s Superman or the Luke of the original Star Wars—I refuse to call it “Episode IV”) or in his grimdark post-90s red-pilled manifestation, this hero leads us again and again through stories in which personal virtue (colored, it may be, with a little of the old ultraviolence) overcomes a corrupt state or institution, reverting always to the status quo ante. Even nowadays, when the savior is less likely to automatically wear a white man’s face (yet it’s amazing how that remains the baseline—I’m looking at you, Timothée Chalamet), that message is hammered home again and again by our corporatized pop culture.

I was programmed, like everyone else, to respond to the fascist sublime, in spite of the uses to which that aesthetic has been put against people like me. I watch the trailer for the latest iteration of The Batman and the ten-year-old boy in me is thrilled, even as the fifty-one-year-old man is repelled by the spectacle of vigilantism, which has historically been directed not against the Riddler and his minions but against Jews and Blacks. I believe that the Patrick O’Brian novels, in their appeal to that ten-year-old boy, offer me something like reprogramming. They draw me in, as the best genre narratives do, into a complete and completely convincing world of high adventure through which I can forget, for a while, the social role assigned to me and identify instead with a hero. But Jack Aubrey is not a callow man of destiny; even if he feels inclined at moments to play that role, there’s always the darker, more ironic character of Stephen Maturin to take the wind out of Aubrey’s sails. Their characters are deeply embedded in the history that produced them and their times, and to read O’Brian’s novels is to learn to read between the lines, to notice what’s left out (often surprisingly large chunks of plot), and to pick up on ironies, some of them embedded by what’s happened in the centuries since Napoleon was banished to St. Helena, that work against ideology and ask readers to think for themselves.

I propose, therefore, to read my way through the novels once again: to begin with Master and Commander and work my way forward, responding to the particular foibles and delights of each volume, drawing what connections I can, and relishing in their central pleasures: the indelible friendship between the two heroes, who are about as different as men can be; the comedy of manners; the unfathomably rich language, “as good as a play,” as one of the characters might say; the surprising depths of feeling; and even what is to me the least interesting yet most integral component of the books, the naval adventures and battles. Should I be led along the way into philosophical digressions, bits of autobiography, further references to Proust, and considerations of what it might take for me to cook up an authentic sea pie, so much the better!2

Proustian flashback to the shelves of Kepler’s Books in Menlo Park, where I spent many a morning or afternoon in my time as a Stegner Fellow in Poetry at Stanford. I would browse with an almost desperate intensity (mostly the poetry section but also in literary theory and occasionally in fiction), looking for the title that would unlock something in me; then I’d buy more books than I could plausibly afford and spend the rest of the day sitting at the little cafe attached to the bookstore, reading and brooding and scribbling in an endless series of notebooks. They sold a sausage sandwich I was fond of, as I recall. I wrote most of Fourier Series at that cafe. I can still picture the shelf in the fiction section with the pastel spines of the Aubrey-Maturin novels all lined up in a pretty row for me to run my finger along, right to left, landing at volume 1.

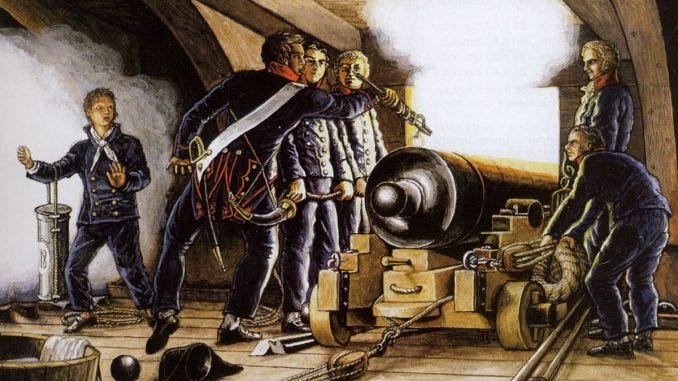

For now I’ll keep these ruminations under the Rarebit Fiend umbrella (there’s no snack that Aubrey and Maturin enjoy more than toasted cheese, after all), but at some point I might choose to give them a distinct identity. [That point has come!] A bow-chaser, incidentally, is the cannon placed in the bow of a man-o’-war to fire when in pursuit of an enemy that one cannot yet engage with the main arsenal of a wooden ship, its broadside. Jack Aubrey has a pair of brass nine-pounders for much of the series that he deploys for this purpose.

I subscribed because I wanted to read the story, "Dream of a Rarebit Fiend"...haha, then I discovered it was the newsletter title...maybe you should write it.

Hell yeah! Please continue writing about O’Brian and more on G. MacDonald would be fascinating. I enjoy your essays a lot.