1

When last we left our heroes, they were in nearly as sad a way as they were in Desolation Island, when the horrible old Leopard was stranded rudderless on a frozen island in the far southern latitudes. But this novel begins cheerfully, as these novels usually do, with the crew of the wrecked Diane playing cricket as a break from the hard work of building a weatherly schooner so that they might rescue themselves from the Pacific island on which they’re marooned. Then they meet a crew of Dyaks, led by a fierce, beautiful young woman by the name of Kesegaran, who seems at first interested in trade, even as Jack is interested in her. But the Dyaks prove treacherous, and in the Dianes’ repulse of their fierce attack, Kesegaran is killed.

It is neither the first nor the last time that Jack and Stephen will be confronted by an anomalously powerful woman; the sexual frisson that precedes Kesegaran’s violent resistance to colonial oppression mirrors the situation at the end of the novel to follow, Clarissa Oakes (aka The Truelove), in which Aubrey will intercede in a dispute between rival island monarchs, utterly destroy the forces of one (allied with the French), and sleep with the congenial queen he aided, who in this case willingly lies back and thinks of the King George of whom she is now nominally the ally.

O’Brian’s approach to British imperialism—freshly on the collective mind since the somehow inconceivable passing of Her Majesty Elizabeth II—is more complex than my description makes it appear. The dyad of Jack and Stephen permits him to explore his ambivalence. Jack, hardly a systemic thinker, or any sort of thinker save in the tactical or mathematic sense, serves king and country unquestioningly, with a faith in institutions (the Royal Navy chief among them) that is only occasionally shaken. Stephen is as usual the more complex figure: an enthusiast for Irish independence whose idealism was wounded by the cruel infighting that magnified the disaster of the 1798 uprising, to the point of making his infamous declaration in Master and Commander that he “would not cross this room to reform parliament or prevent the union or to bring about the millennium.” But by the second novel he has recovered enough of his passion for freedom to work on behalf of Catalan independence by doing intelligence work for Britain, the lesser of the two weevils struggling for world domination in this period. As the series goes on, his anti-imperialist sentiments are deployed more globally; by its end, his work to undermine the Spanish Empire in South America will be as or more important as his covert war against the tyrannical Bonaparte. He is if you like the conscience or superego restraining Jack’s imperial id. We love Jack, as Stephen loves him, and he is very good company. But the man, like his monarch, is a pirate at heart, whose sense of duty and honor is sometimes little more than a fig leaf for his love of conquest.

2

Kesegaran is a curious name: in Malay the word means something like “freshness,” and it is one of the titles with which the British envoy greeted the Sultan of Pulo Prabang in The Thirteen-Gun Salute: Kesegaran mawar, bunga budi bahasa, hiburan buah pala, translated by the unfortunate Edward Fox as “Flower of Courtesy, Nutmeg of Consolation, Rose of Delight.” The middle epithet becomes the title of the book we are reading, as well as the name Jack gives to the tidy little 20-gun post-ship that becomes his next command after he and his crew are rescued by some Chinese traders who happen by the island. But there is nothing happenstance or innocent about that name.

Amitav Ghosh is an Indian novelist whose book-length essay, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, has haunted me since I read it in 2017. Very briefly, Ghosh argues that the novel as a form, preoccupied as it is with the “moral career” of individuals, is ill-suited to represent or respond to the great derangement of global climate instability, which is necessarily the story of systems and collectives. Ghosh’s argument hovers now in the back of my mind every time I sit down to read a novel—or try to write one. As Bill McKibben said in a recent edition of his own Substack, global heating is now “the overriding human story,

and will be for the (un)foreseeable future. You would think, wouldn’t you, that a series of adventure stories begun in the late 1960s and concluded circa 2000, and thus written before climate change was recognized or taken seriously by most people, would be innocent of these concerns. Reading them now, they may seem to offer a momentary escape from the darkness of our historical present in much the same fashion as secondary-world fantasy novels like The Lord of the Rings.1 But I don’t read the Aubrey-Maturin books that way. They are far too concerned with the details of the natural world as it began its decline in what was already a fairly advanced state of globalized imperialism. There is a heartbreaking dissonance between the quasi-religious awe Stephen experiences in the face of new species and other natural wonders, and a reader’s consciousness of the degraded state of nature today—a consciousness bitterly underlined by the cheerfully wanton slaughter of wildlife practiced by Stephen’s shipmates.

Under such circumstances, the book and ship called The Nutmeg of Consolation take on a keenly ambivalent, even uncanny quality. Ghosh’s new book, a sequel to The Great Derangement is called The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. Full disclosure: I have not yet actually read this book. But I’ve read enough about it, and read enough interviews with Ghosh, to recognize its peculiar applicability to my project of rereading O’Brian, for whom the earth and its creatures is never inanimate, never simply raw material upon which some lordly hand must bestow a form.

There are many, many colonial commodities that most of us don’t think about—commodities permanently stained by their association with the extractive economy of imperialism. Today it’s your iPhone, assembled in inhuman conditions in a Chinese factory; in a Jane Austen novel, particularly Mansfield Park, we must remember to associate the sugar stirred by the characters into their tea with the sugar cane harvested in brutal conditions by enslaved people in Jamaica and other British colonies. Ghosh’s book focuses on nutmeg, a spice that originates in the Banda Islands of eastern Indonesia; as even Wikipedia can tell you, it is at the center of the spice trade that motivated European colonialism in the Pacific, beginning with the slaughter of the inhabitants of the Banda Islands by the Portuguese in 1511, almost exactly three hundred years before the events of O’Brian’s novel. That’s a long time! The colonial project is older than Columbus, and the world and its present welter of problems was fully formed by the time Jack and Stephen met in that music room in Mallorca.

I don’t know if O’Brian thought very hard about the significance of nutmeg as a signifier of colonialism when he used it as an epithet for a Sultan who allies himself with the British (since remaining completely independent and non-aligned is not an option). It then becomes the name of a British man-of-war that, significantly, was once a Dutch ship (the Dutch record of colonial atrocity is particularly horrendous) that had been entirely submerged to cleanse it of plague. Stephen, incidentally, repeatedly wonders at the sweetness and cleanliness of the ship, as though it were perfumed by the titular spice; when he returns to the Surprise he is surprised and dismayed by the stink. The metaphor writes itself.

Both ship and novel concern themselves with colonialism at its ugliest and most destructive. The most disquieting manifestation comes in an eerie episode in which the Nutmeg arrives at Sweeting’s Island, a remote island in the vicinity of Palau, in search of antiscorbutics. There they discover that nearly all of the island’s native inhabitants have died of smallpox, probably caught from whalers—another manifestation of imperialism’s ruthlessly extractive logic. “There is something horrible there,” an appalled seaman reports when they land, in a perhaps deliberate echo of Conrad’s Kurtz. The horror invades Jack as he, Stephen, and Stephen’s assistant Martin explore the village of corpses:

Again Jack followed them as they went along, talking of the nature of the disease and of how badly it affected nations and communities that had never known it in the past—how mortal it was to Eskimos, for example, and how this particular infection must have been brought by a whaler, its visit proved by the axes. He felt a certain indignation against them, a resentment for his own unshared horror, and when Stephen turned to him as they joined the others and said “I believe we may take coconuts here, and fruit and greenstuff, robbing no man,” he only answered with a sullen look and a formal inclination of his head.

I am reminded here of nothing so much as one of the “away team” missions of the USS Enterprise on Star Trek, in which Kirk, Spock, and McCoy explore the devastation of an alien planet, with Kirk and McCoy responding viscerally and emotionally while Spock responds with his usual cold logic. O’Brian’s enterprising crew do not draw any overt connection between their own activities in the Royal Navy and the devastation wrought by whalers, either to the whales themselves or to the people they inadvertently destroy. But they do feel a certain obscure responsibility—O’Brian is very good at depicting processes of moral intuition that are rarely formally described. There are two survivors on the island, a pair of little girls, at first mistaken for apes. Martin, who you’ll recall is a parson as well as a medical man, reacts in a clumsy but ultimately good-hearted way:

“Clearly, we cannot leave them here to starve,” said Martin. “But Lord, Maturin, if only they had been our nondescript apes, how we should have amazed London, Paris, Petersburg… Come, child.”

Martin’s response to the little girls implicates the most innocent-seeming practice in these novels—naturalizing and botanizing—in the imperial project. If only the little girls had been a new species of ape, how they would have amazed the scientific world! Behind this wish is a darker one: if the girls had been apes, the men would feel no responsibility for their welfare. But they are human beings who will die if left to themselves. And so they come aboard, are christened Emily and Sarah Sweeting, and Stephen, treated more or less as their owner, must decide their ultimate fate.

The last section of the novel concerns itself with a trip to Botany Bay in Australia. It’s not the first visit for our heroes to this colony; you may recall that the original mission of the Leopard in Desolation Island was to assist Governor William Bligh (yes, that Bligh) with a settlers’ rebellion in New South Wales. That trip was curiously elided; we hear a little bit about it in The Fortune of War, but we never get to meet Bligh or see anything of Australia. This time we get a long look at Sydney—”squalid, dirty, formless” as Stephen describes it in a letter to Diana. The colony was, at the time, a vast open-air prison, and Stephen is appalled by the condition of the convicts and the brutal treatment of their overseers; there is almost nothing of the veneer of civilization and culture that we’ve seen in other colonial capitals, nor do we see a vital native culture or cultures (as in the Indian scenes of HMS Surprise) pushing back. The landscape itself is peculiarly inhospitable—not in the literal sense, though certainly many European settlers found it so, but inhospitable to being romanticized (or as Ghosh might put it, terraformed in the image of Europe. As Martin remarks, though the country “is a naturalist’s treasure house… it is wanting in wild romantic prospects or indeed anything that makes a countryside worth looking at, apart from its flora and fauna.” Stephen responds:

‘I remember Banks telling me that when first they saw New Holland and sailed along its shore the country made him think of a lean cow, with bare scraggy protruding hip-bones. Now you know very well what affection and esteem I have for Sir Joseph; and I have the utmost respect for Captain Cook too, that intrepid scientific mariner. But what possessed them to recommend this part of the world to Government as a colony I cannot tell – Cook, who was brought up on a farm; Banks, who was a landowner; both of them able men and both of them having seen great stretches of its desolation. What infatuation, what willful …’ He broke off, and Martin said, ‘Perhaps it seemed more promising after so many thousand miles of sea.’

Raw, “starve-acre” Australia cannot conceal from European eyes the manifest ugliness of its own colonial project. We encounter only one indigenous Australian, who goes by the name of Ben, “a morose bearded middle-aged Aboriginal” with whom Stephen has difficulty communicating, as “he and his people have no notion of property.” Stephen, who has just learned that his apparent bankruptcy due to the failure of his new bank was only a mirage, for he had absent-mindedly failed to sign his power of attorney properly, reflects: “To us property, real or symbolical, is fundamental; its absence is known to be misery, its presence is thought to be happiness. The language of our minds is wholly different.” Australia cannot be claimed as mental, emotional property, which is Stephen’s favored mode of colonization, only apparently more innocent than the actual seizure of land. In this context, one of Stephen’s remarks from Post Captain takes on a new, more ominous resonance: “Any innocent pleasure is a real good: there are not so many of them.”

3

As usual I find myself following Stephen’s adventures more closely than Jack’s; I am developing a theory that the first read-through or circumnavigation of “the canon” of Aubrey-Maturin novels will be for most people Aubrey-oriented, since his character and decisions turn the fundamental plot, whereas re-reads will belong, increasingly, to the more complex character of Stephen. At any rate, it is Stephen’s moral career in the last few chapters that concerns me most. Fearing that dark-skinned Melanesian islanders are unlikely to thrive in Britain, Stephen hatches a scheme to give Sarah and Emily to an orphanage managed by Mrs. Macquarie, the wife of the colony’s governor. The girls, however—who have thrived on board ship and now speak perfect English (both quarterdeck and lower-deck dialects)—are dismayed, to put it mildly, at this prospect. This is partly because they have already, in a few brief months on an English ship, internalized the ambient racism, calling the indigenous people they see “black boogers” and recoiling from them in horror. More significantly, they have bonded with the crew of the Surprise, particularly Jemmy Ducks, the ship’s poulterer directly responsible for their care. They are part of the crew, which is of course a kind of extended substitute family. (In this Sarah and Emily bear a distinct resemblance to Jack’s own little girls, Fanny and Charlotte, themselves largely raised by seamen and fluent in their lingo.) Stephen is peculiarly blind in this decision, having described the colony to which he would consign his charges as “an utterly inhuman place.” Fortunately, the girls escape the orphanage and return to the Surprise, “declaring that they should never leave her again.” “On my part,” Stephen realizes, “the move was one of those reasonable, wise, profoundly mistaken actions.” And so the girls remain with the crew.

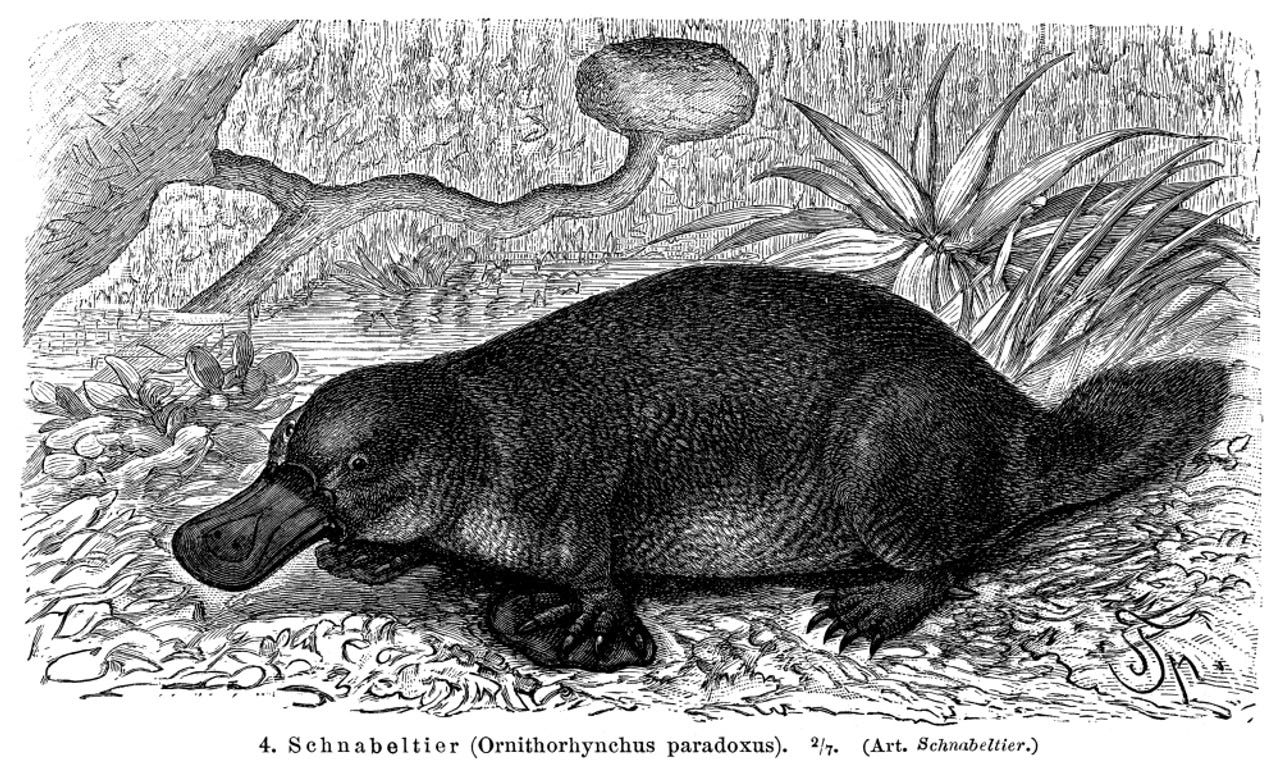

Stephen’s most positive action is the liberation of his Irish servant Padeen Colman, transported to New South Wales for the crime of breaking into an apothecary’s shop in search of the laudanum to which he had become addicted. He has suffered abominably as a convict and Stephen is convinced he will soon die if abandoned. Feeling responsible, Stephen plans to bring Padeen aboard the Surprise, but runs into a wall by the name of Jack Aubrey. He has pledged to the suspicious Sydney authorities that he will not permit any convicts to escape on his ship, and when Stephen tells him of his plan to rescue Padeen, Jack turns him down flat. Now it is Jack who behaves in a reasonable, wise, profoundly mistaken way. Their confrontation echoes the other time the two friends have come closest to breaking, when they were both involved with Diana Villiers; now it is the bond of shipmates which is at stake. Then, they prepared for a duel that was only averted by the need to take their ship into action. This time, the break is averted by Jack’s rescue of Stephen from his folly—in this case, handling a duck-billed platypus that stings him, almost fatally. In his rush to preserve his friend’s life, Jack relaxes his moral rigidity and does what the reader always hoped he’d do—he rescues Padeen as well.

4

I am tempted to write an entire post about O’Brian’s habit of populating his novels with writer characters, minor winking facets in the complex self-portrait he creates. There’s the hapless, aptly-named Mr. Scriven, the starving inhabitant of Grub Street who tried to rob Jack Aubrey in Post Captain; the nearly as abject Michael Herapath, translator of Chinese poetry and Stephen’s catspaw; the competing poet-lieutenants Mowett and Rowan; and now John Paulton, a friend of Martin’s who mistakenly believed that a novelist could live better in New South Wales than he might in London. Stranded in a cultural desert, indifferent to birds and beasts, starved for intelligent conversation, he asks Stephen somewhat anxiously if he as a scientific gentleman takes any notice of novels:

“Sir,” said Stephen, “I read novels with the utmost pertinacity. I look upon them—I look upon good novels—as a very valuable part of literature, conveying more exact and finely-distinguished knowledge of the human heart and mind than almost any other, with greater breadth and depth and fewer constraints.

Leave it to a novelist to defend the practice of novel-writing in his novel! And it’s hard not to detect the twinkle in O’Brian’s eye when Paulton despairs of ever finishing his book, to which Martin makes this response:

‘As for an end,’ said Martin, ‘are endings really so very important? Sterne did quite well without one; and often an unfinished picture is all the more interesting for the bare canvas. I remember Bourville’s definition of a novel as a work in which life flows in abundance, swirling without a pause: or as you might say without an end, an organized end. And there is at least one Mozart quartet that stops without the slightest ceremony: most satisfying when you get used to it.’

A better description of the Aubrey-Maturin series, which terminates abruptly in the midst of the unfinished novel known simply as 21, cannot be imagined.

Can novels, with their necessary preoccupation with the fates of individuals, respond adequately and appropriately to a phenomenon as global and entangling as climate change? I don’t quite know the answer. But certainly the Aubrey-Maturin series can be read, and I think demands to be read, perhaps only a little against its own grain, as an abundant and many-leveled portrait of liberal ideology that is also, at times piercingly and unforgettably, a critique of that ideology and the violence at its heart. And there’s no question in Ghosh’s mind, or in mine, that that ideology is at the heart of the climate crisis, which demands a response at least as comprehensive and imaginative, if perhaps differently focused, than what O’Brian has achieved.

Speaking of the violence of liberal ideology, my book of speculative poetry, Hannah and the Master, is finally available from bookstores and from rhymes-with-Spamazon. How’s that for a sales pitch? It’s doomy, it’s dreamy, it’s poetry! Get yours today.

I’ll put aside for the moment the argument that the imagination of alternative worlds has its own political utility—that escapism has a progressive potential that does not necessarily reinforce the status quo. For more on that, see this wonderful essay by the late Javier Marias, “Seven Reasons Not to Write Novels and Only One Reason to Write Them.”