1

Violence and hardship are frequently the lot of Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin, but these circumstances are balanced, novel by novel, by our heroes’ (generally) honorable behavior and their (sometimes outrageous) luck. Jack’s trusting nature leaves him vulnerable to swindlers and projectors, while Stephen’s melancholy introversion and habits of secrecy threaten at times to cut him off from humanity. They are participants in war, and O’Brian spares them (and the reader) little when it comes to wounds and crueler losses. Their enemies are numerous and sometimes ruthless; Stephen’s torture at the hands of French agents in HMS Surprise leaves lasting marks. But more often the enemy behaves honorably, even with courtliness—witness the enduring friendship between our heroes and the French captain Christy-Palliere. Real evil does not frequently darken O’Brian’s pages and when it does, as in the eleventh novel, we must take note.

What do I mean by real evil? Up to this point in the series there have been any number of evil actions and characters who do evil things—but O’Brian’s villains, like Shakespeare’s are entirely human, and he nearly always renders that humanity visible. He can even do this at a distance, as he does in Desolation Island with the barely seen Dutch captain of the Waakzaamheid, whose Ahab-like pursuit of the Leopard is explained, in Jack Aubrey’s mind at least, by the desire for revenge after the Leopard’s cannon have killed a relative of his—”His boy, perhaps, dear God forbid.” Another example comes from the novel preceding this one, The Far Side of the World, and the tragic case of the gunner, a man named Horner, who murders his nineteen-year-old wife and her lover and subsequently hangs himself. Horner is a crude and violent man who suffers as much from inarticulacy as he does from sexual impotence, yet O’Brian still extends the empathic sense that his grisly actions derive from a toxic masculinity as fatal to the gunner as it is to his hapless victims.

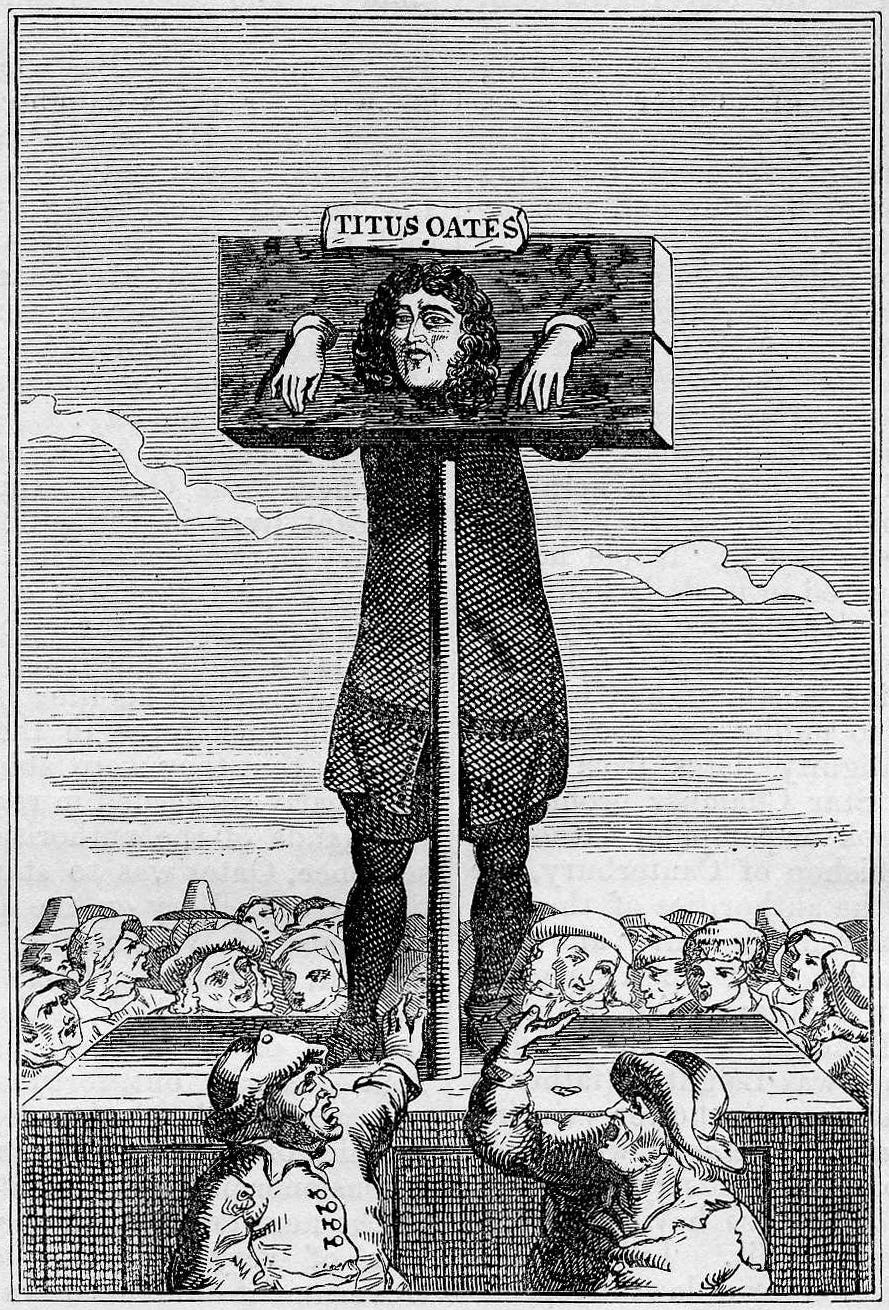

The action of The Reverse of the Medal is nearly all upon land, as was the case for half of Post Captain and nearly all of The Fortune of War. Having returned from a successful mission to the Pacific in pursuit of the heavy American frigate Norfolk (the ship, which had been harassing the English whaling fleet, came to grief in a storm and its crew was captured by the Surprise after a tense week or so on a desert island), Jack Aubrey rescues a man calling himself Ellis Palmer (Palmer appears to be one of O’Brian’s favorite names) from some ruffians at an inn. The grateful Palmer tells Jack that peace is going to be declared in a few days and now is the time to buy government shares; Jack does so, and out of filial duty urges his appalling father, General Aubrey, and his cronies to do the same. (Once again O’Brian draws upon the life of Lord Cochrane, his model for Jack Aubrey, in telling this story.) This leads over the course of the novel to Jack’s being arrested, imprisoned, convicted, and pilloried for the crime of rigging the market.

Meanwhile Stephen arrives in London in search of Diana (as he did in Desolation Island) and once again finds that she has quit the place in which she was living and run off with a lover—in this case the absurdly handsome Swedish attaché, Jagiello. This is in retaliation for Stephen’s apparent affair with Laura Fielding in Malta—an entirely chaste affair conducted for the purposes of intelligence. Stephen’s heartbreak is intensified by what he believes to be Diana’s intemperate haste and her apparent disregard of the letter of explanation he had asked Andrew Wray to give to her two books ago. He has no notion that his misfortune and Jack’s are allied, designed as they were by the same agent. Wray and his partner-in-treason Ledward have rigged the market to benefit themselves, using the unwitting Aubrey as their catspaw; not delivering the letter Stephen entrusted him with is the most casual but perhaps the most painful of the blows dealt by Wray, who has been plotting Stephen’s downfall for the last two or three books.

Andrew Wray comes into his own as villain in this novel. Introduced rather casually as a mere scrub cheating at cards in Desolation Island, he becomes an attractive, nearly sympathetic figure as we learn about his love of music and his idealistic passion for the Bonapartist millennium in Treason’s Harbour. True, in that same novel he has married Admiral Harte’s daughter Fanny against her will (she loves little Babbington) for the sake of her money, since he is addicted to gambling. He is also described as having a “paederastic” disposition, though O’Brian is scrupulous throughout the series in presenting homosexuality as entirely natural, a quality he distributes impartially to characters sympathetic and otherwise. (As Stephen puts it in H.M.S. Surprise, “each man must decide for himself where beauty lies and surely the more affection in this world the better.”) He is flighty, brilliant, lacking in bottom, greedy, and desperately unhappy. His machinations are largely presented in their effects in this novel—we don’t see him planning or executing them, as we did in Treason’s Harbour. But we get at least two chilling glimpses of Wray’s real malevolence—when the man takes off the mask.

Both of these occasions take place when Stephen visits Wray’s house—bearding the dragon in its lair. Wray has been avoiding Stephen, but Stephen misunderstands the reason—he thinks it’s because Wray doesn’t want to be dunned for the enormous gambling debt he owes Stephen, who all but ruined Wray at picquet in Treason’s Harbour. When he finally corners him, Wray tells the lie that Diana had already decamped from Half-Moon Street with Jagiello before he, Wray, had an opportunity to deliver Stephen’s letter. A disheartened Dr. Maturin thanks him and leaves:

‘I am obliged to you, sir,’ said Stephen, and he took his leave. If he had seen Wray watching him from behind the lace curtain, grinning and jigging on one leg and making the sign of the cuckold’s horns with his fingers he would quite certainly have turned and killed him with his court sword, for this was a very cruel blow. It meant that Diana had not waited for any explanation, however halting and imperfect, but had condemned him unheard; and this showed a much harder, far less affectionate woman than the Diana he had known or had thought he knew – a mythical person, no doubt created by himself. It had of course been evident from her letter, which made no reference to his; but he had not chosen to see the evidence and now that it was absolutely forced upon his sight it made his eyes sting and tingle again. And deprived of his myth he felt extraordinarily lonely.

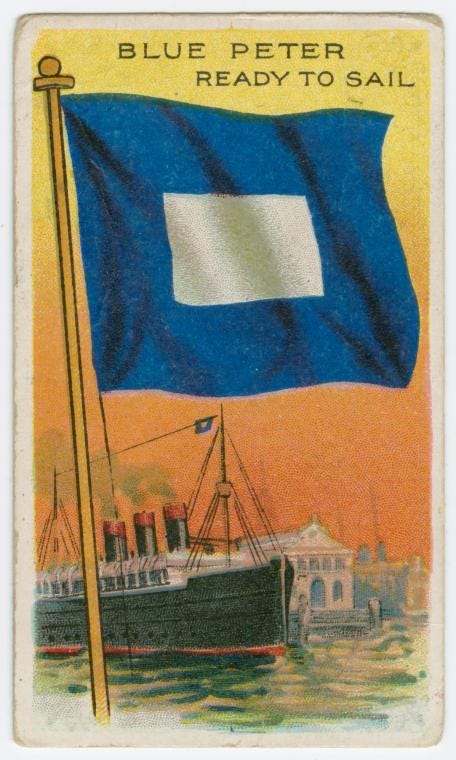

What strikes me here is not so much Wray’s gleeful display of odiousness as the nature of the crime he has committed: he has killed the myth of Diana that Stephen had permitted to rebloom in his heart after she gave up her great diamond, the Blue Peter, to win his life and freedom in The Surgeon’s Mate. There seems to be no greater crime in O’Brian’s universe than this murder of the inner life, of one’s most precious fantasy, even as the narration never lets the reader forget that it is fantasy. Wray’s murder of Stephen’s myth anticipates and mirrors the metaphorical murder that he commits with Jack, for his punishment for the crime of rigging the market is to be struck from the Navy list—to be, as it were, dishonorably discharged. The Royal Navy is consubstantial with Jack’s very being; to be separated from it is, for him, a kind of living death.

Stephen’s myth of Diana, the woman for whom grace of movement somehow substitutes for morality, died once before—when he saw the coarse survivor she’d become while living as mistress to the American spymaster Johnson. That myth was resurrected by her sacrifice of the Blue Peter. The hint of its second (third?) coming arrives at the climax of this novel, when the French spy Duhamel unexpectedly returns, bearing with him the diamond and also evidence of the treachery of Ledward and Wray. In a flash Stephen realizes the depths of Wray’s violation, for which Stephen will eventually extract his revenge in the most chilling possible fashion. But we mustn’t get ahead of ourselves.

2

I said that Stephen comes to Wray’s house twice, and both times we get a glimpse of the malevolence behind the mask; the second time, Stephen shares in the glimpse. The novel is in its last chapter: Aubrey has been found guilty and his innocent trust in the law (“everyone agrees that English justice is the best in the world”) destroyed. Still unaware of Wray’s treachery, Stephen goes to his house hoping that Wray’s influence might prevent Jack’s being struck off the Navy list. This is a fate far worse than the pillorying to which Jack has been sentenced, a barbarous affair that might result in his blinding or maiming by the mob of onlookers. Wray is not at home, but his wife is, and the former Fanny Harte sympathizes with Aubrey’s plight, remarking in passing that her husband “made a great deal at the same time.” As he is leaving, Wray comes in, a ghastly drunken specter:

Two chairmen supported Wray up the steps; two footmen took him over with practised hands; and as they propelled him across the hall he turned his blotched face towards Stephen and said

‘A beaten wife and a cuckold swain

Have jointly cursed the marriage chain.’

Wray is quoting Mary Wortley Montagu’s bitterly cynical poem, “Epitaph,” which I shall here reproduce in full:

Here lyes John Hughs and Sarah Drew

Perhaps you'l say, what's that to you?

Believe me Freind much may be said

On this poor Couple that are dead.

On Sunday next they should have marry'd;

But see how oddly things are carry'd.

On Thursday last it rain'd and Lighten'd,

These tender Lovers sadly frighten'd

Shelter'd beneath the cocking Hay

In Hopes to pass the Storm away.

But the bold Thunder found them out

(Commission'd for that end no Doubt)

And seizing on their trembling Breath

Consign'd them to the Shades of Death.

Who knows if 'twas not kindly done?

For had they seen the next Year's Sun

A Beaten Wife and Cuckold Swain

Had jointly curs'd the marriage chain.

Now they are happy in their Doom

For P. has wrote upon their Tomb.

Montagu satirizes an uncharacteristically sincere poem of Alexander Pope’s (“P. has wrote upon their Tomb”), “Epitaph on Two Lovers Struck by Lightning,” in which the eponymous lovers’ surprising fate is a kind of divine approbation of their pure love. But for Montagu, the lovers’ death by lightning is a random event that saves them from a much crueler fate: marriage.

Wray’s cynicism, borrowed in this case, is the central expression of O’Brian’s vision of evil; evil, for O’Brian, is an entirely negative and nihilistic force. He and his heroes are Romantics, self-consciously adhering to habits of thought and conduct that, circa 1812, are already perilously out of date. Marriage, for O’Brian as for Jane Austen, is one of the central symbols or institutions warping beyond recognition under the pressures of incipient modernity. Their characters must thread the needle between marriage as a cold-bloodedly economic proposition on the one hand, and the demands of the love-match on the other. Stephen’s marriage to Diana is only curious for how openly it manifests these stresses: she rejects him when he is penniless, then again when he has the means to offer her a position but she senses that his love for her has faded. That love can only be revived by her sacrifice of a diamond as big as the Ritz, a diamond whose name, the Blue Peter, signifies departure and an outward-bound ship. Yet even after they are married they scarcely live together, and since they were married aboard ship and not by a priest, for Stephen at least the connection retains a touch of the illicit (in a farewell letter Diana seems to acknowledge this: “she was glad, yes so glad, that they had never been married in a Christian or a Roman Catholic church”). Their marriage is mythless, and thus precarious.

The most solid marriage in the novels is that between Jack and Sophia, though O’Brian makes clear that it has serious imperfections—Jack is sometimes unfaithful and too often away, while Sophia dislikes sex and has a jealous temperament, not to mention a gorgon of a mother-in-law (though Mrs. Williams, a worshipper of capital, is entirely supportive of Jack’s supposed fixing of the market). What Jack and Sophie have to counter cynicism and the decay of trust is a capacity for forgiveness—Sophie especially. We see this in operation at the climax of a subplot for which O’Brian has been preparing from the very first novel: Jack’s affair as a midshipman with “a likely black girl called Sally.” This affair is of signal consequence for Jack: in the short term, it gets him disrated, so that he spends six months before the mast as a common foremast hand and so learns the ways of the lower deck to a degree rare in officers, ultimately benefiting his career. In the long term, as he discovers to his shock, it has produced a now-adult son who comes aboard the Surprise in Barbados:

They looked at one another with a naked searching, eager on the one side, astonished on the other. There were few mirrors hanging in Jack’s part of the ship – only a little shaving-glass in his sleeping-cabin – but the extraordinarily elaborate and ingenious piece of furniture that Stephen’s wife Diana had given him and that was chiefly used as a music-stand had a large one inside the lid. Jack opened it and they stood there side by side, each comparing, each silently, intently, looking for himself in the other.

Is it significant that Diana’s present to Stephen provides the means by which Jack and his newly discovered son, Sam Panda, come to recognize themselves in each other? Perhaps it is. Jack’s astonishment gives way to hesitant pride in this fine and manly son, though he is initially dismayed by his Blackness and his Catholicism (Sam’s ambition is to become a priest). “There is nothing wrong with being black, brother,” Stephen assures him; “The Queen of Sheba was black, and a fine shining black too, I am sure.” But what really makes Jack uneasy is that Sam, before coming to meet his father, had first paid his respects to Mrs. Aubrey at Ashgrove Cottage. Although, Jack tells himself, Sophia can hardly cavil at him for his having had an affair years before they met, he understands the emotional fraudulence of this stance, especially given his more recent bouts of infidelity. How will she react to such palpable evidence of Jack’s lust, and in such a surprising package?

Eventually of course Jack makes his way home, and after the reunion has been deferred a few times, finds himself alone with Sophie, and mentions the last letter he’d received from her—the letter carried by Sam. Here is her reaction:

“Oh yes,” cried Sophie. “The one that kind, attentive young man offered to carry. And so he found you, then? I am so glad, my dear.” She looked at him, hesitated, and then flushing a little she went on, “I thought him so particularly amiable, all one could wish in a young man, and very much hope he will give us a long visit as soon as ever his duties allow. I should like very much the children to know him.”

I find this extraordinarily moving. It’s one thing for Sophie to forgive Jack his peccadillo, quite another to welcome Sam into the family, as she does here. This capacity for imaginative sympathy—a sympathy that enlarges one’s connections and one’s world—is the polar opposite of Wray’s cynical nihilism. Sophia—her name means wisdom, after all—overcomes jealousy and fear with her love.

3

“The role of deus ex machina is not one that I care for, at all,” reflects Stephen. Having inherited from his godfather, one of the richest men in Spain, Stephen is able to purchase the decommissioned Surprise and turn it into a private man of war or letter of marque, thus offering the no-longer Captain Aubrey a floating refuge from humiliation. But O’Brian himself resorts to deus ex machina rather frequently; there is the inheritance itself, and there is also the fact that it is the sudden return of Duhamel, not any insight or efforts made by Jack or Stephen themselves, that finally reveals the villainy of Wray. (O’Brian kills Duhamel off in the next book, almost it seems out of embarrassment at the character’s purely functional role.) There are nihilistic fictions, to be sure, and darkness nips around the edges of the Aubrey-Maturin saga, giving it depth and motion. But the story O’Brian wants to tell is implicitly positive—as in the Hornblower novels of his predecessor C.S. Forrester, over the course of the novels we will see Jack Aubrey rise, from lieutenant to commander to post captain to admiral, albeit with some hitches, of which his disrating is by far the most serious. This is the series’ lowest point—other lows will occur, some of them shocking, but at this moment, only the benevolence of the author can save our heroes from moral dissolution.

Coming up: a review of George Albon’s The Tiers, a wonderful manuscript of lockdown poems that George was kind enough to share in response to my own shelter in place. With any luck this may lead to some enterprising publisher’s coming forward to publish The Tiers, which I found to be affecting and philosophical and hilarious, sometimes all at once.

I also have thoughts to share regarding Gerald Murnane’s second novel, A Season on Earth, republished for the first time in its full form a couple of years ago. It’s a fascinating early work that makes explicit what’s implicit in his other writing, and which I found affecting in its almost autistic and certainly autobiographical portrayal of the grandiose solipsism of a young Australian Catholic in the 1950s, tragicomically unable to distinguish between the real world and the world of his imagination.

My novel How Long Is Now is still new by any meaningful sense of that word, and I am hopeful that you might buy it and read it and review it. I have copies to send to reviewers, if you happen to want to write one; send your address to corey@lakeforest.edu.