A Bit of a Want

Friendship and salvation in Hear My Song (1991)

Longtime readers of the Fiend know that for a good while my writing was devoted to an enthusiast’s study of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin series. There’s so much to love about those books—the nautical poetry, the adventure, the Austenesque marriage plots, the travel, the moral sophistication, the subtle anti-imperialism. But readers know that the heart of those books is the unlikely friendship between the bluff, extroverted Captain Jack Aubrey and the melancholic, introverted Doctor Stephen Maturin. Fictional characters are not our friends; parasocial relationships with them probably aren’t much better than obsessing after celebrities and influencers. Reading books is no cure for loneliness. And yet. In a time when men are lonelier than ever, and when the loneliness of young men in particular is a plague upon society, depictions of male friendship offer a beacon, a guide. To become aware of one’s appetite is the first step to satisfying it.

Depictions of male friendship in literature and film fascinate me for the hints they offer about what men—so ill-trained, generally speaking, in acknowledging their feelings, let alone expressing them—need to flourish and get past the temptations of misogyny and MAGA. I had many important friendships in my twenties and thirties, but it wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to consciously cultivate friendships with other men. (I owe that conscious cultivation, in part, to my wife’s encouragement, but the role that women play in gentling and civilizing men is a topic for another day.) As a result, I now have a network of guys with whom I don’t simply hang—we can actually talk to each other. Men who refuse to be vulnerable with each other—too scared to let other men see our fears and anxieties about marriage, aging, parenting, career disappointments, struggles with substance use, and so on—become vulnerable to hucksters, simplistic ideologies, and us/them thinking. Men in the aggregate, without the bonds of friendship, become a resentful, seething mob.1

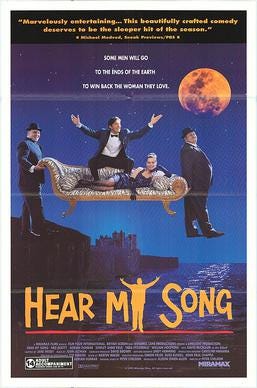

So my thoughts drift back to one of my favorite movies, which I first saw when I was still a college student, an obscure little number from 1991. It’s a British-Irish film, directed by Peter Chesolm (who?) and starring no one you’ve heard of with the possible exception of Ned Beatty. It’s called Hear My Song, and it’s a sentimental gem.2

The plot is simple. An Irish impresario with a conman’s soul, Mickey O’Neill (Adrian Dunbar, who co-wrote the film), owns Hartley’s, a struggling Liverpool nightclub. To keep it afloat, he books a legendary Irish tenor, Josef Locke, a tax exile subject to arrest the moment he sets foot on English soil. The singer he hires, “Mr. X” (a sublime William Hootkins), turns out to be a fake, but this doesn’t prevent Mickey from foisting the guy on an old flame of the real Locke, Cathleen Doyle (Shirley Anne Field), the mother of Mickey’s dental hygienist girlfriend Nancy (Tara Fitzgerald). When Cathleen reveals the fraud, Mickey loses his club, his girl, his friends—everything. In order to get them back, he goes home to Ireland on a mission to find the real Josef Locke (Ned Beatty). Hijinks ensue.

These hijinks are, quite literally, the heart of the film. In its middle section, the desperate and destitute Mickey stows away on a Dublin boat, finds Fintan in his office (he’s a theatrical agent with a map on his wall which, as his secretary proudly tells Mickey, shows that “every client is represented by a pinhead”), and drags him away from job and family to play Sancho to Mickey’s Don Quixote, driving around the stunningly photographed Irish countryside in search of Joe Locke. When they finally track him down, in an uproarious scene in a rural pub where Locke leads his gang of aging miscreants through a bit of improvised dentistry, Mickey must somehow persuade the singer that he isn’t just a self-interested little shit but a man in love—something he’s been previously unable to say, or show, to Nancy herself.

Fintan and Mickey are old school chums, both of whom sought out careers in the entertainment industry, though not as performers. In one scene, in the intimacy of a little tent in which they sleep side by side, they reminisce about the old days:

MICKEY: Do you ever see any of the rest of them?

FINTAN: Now and again. I see Kieran a wee bit. He’s married. He’s got seven children. We heard you were doing really well. There was even some rumor about you going steady. Course, I didn’t believe any of that.

MICKEY: Aye, I blew it. Mrs. Keegan was right: there’s a bit of a want in me. I don’t know what it is, though.

FINTAN: Ah, well, she was right about all of us.

Mickey is egotistical, selfish, sly, wildly charismatic, whose favorite line to try out on disarming older authority figures goes likes this: “I’m thirty. I was born in peacetime. I haven’t been where you’ve been. I haven’t seen what you’ve seen. And yet…” There’s a bit of a want in me. Mickey tries to turn that want, that lack, to his advantage. It never works, but he keeps trying. Only when Joe Locke dangles him over a cliff, demanding Mickey explain why he keeps persecuting him, is Mickey able to admit to the singer and to himself that “I’m doing this for Nancy. The woman I… love.”

Mickey would have never arrived at this moment of truth without poor, patient Fintan, a self-effacing figure who proves to be as much Virgil as Sancho. When the two of them are lost, Fintan insists it’s because of “the fairies. They are bastards.” He has them both put on their coats inside-out to appease them. When Mickey, in a farcial moment at a cattle auction, ends up outbidding Locke on a cow while waving to try and get his attention, it’s Fintan who comes up with the seven hundred quid the animal costs. Crucially, when the two of them have finally gotten inside Josef Locke’s house, and Mickey is floundering with his “I was born in peacetime” bit, Fintan buys him time by offering to repair an old clock that had belonged to Locke’s father—never mind that Fintan knows nothing whatever about clock repairs. Fintan gives and gives, and then he gives some more. The first thing Mickey does when he shows up in Dublin is borrow money from Fintan to pay for a cab. Later, having spotted Locke and his dog by a stream, he forces Fintan to abandon the rather tasty-looking breakfast of trout he’s cooked up to chase after the man. At another point he drags Fintan out of a phone booth where he’s been trying to make amends to his family for running off—we see the dangling receiver and hear a little girl’s voice lisping Daddy? Daddy? Why does Fintan put up with this selfish bounder? What’s the percentage?

When Mickey finally admits the truth to Joe, and revives in him his memory of Cathleen Doyle, Joe agrees to help him by returning to England, risking his own freedom. There’s a curious little epilogue to this sequence where a still suspicious Joe warns Mickey against trying to deceive him, telling him there’s a well on his property that no one knows how deep it is, and that Mickey will end up at the bottom of it if he isn’t careful. Mickey, exultant at his victory, brings Fintan out to see the well and to test its depth. He drops a coin in it: no sound comes back. Next he drops in a big rock. “This is pointless,” says Fintan, leaving the frame, as Mickey counts: “One… two… three.. four…” By ten, Fintan has returned: “I hate things like this,” he frets. By seventeen there’s still no sound. Now it’s Fintan who’s on fire to get to the bottom of Joe Locke’s well. They pick up a massive wooden beam neither man could have managed on his own, and drop it in: “Take that you great big gaping hole!” Fintan cries. Of course it turns out that the cow they’d brought for Joe is chained to the beam; slapstick ensues. At the last possible moment Mickey smashes the chain with a rock, saving the cow—and what seems like minutes after they dropped the wooden beam the two men hear a distant splash.

There’s a bit of a want in me, says Mickey. Take that, you great big gaping hole, says Fintan. Each man addresses a lack that the other fills. Scheming Mickey needs a Fintan to ground him, to offer him, in the quietest way, the moral education he needs to stop being a gobshite and to step up to his responsbilities as a man. Phlegmatic Fintan needs Mickey, too. He brings adventure into Fintan’s otherwise staid, conventional life; even the simplest conversation with the man brings risk. But it isn’t quite that simple, as the scene with the well shows. It harkens back to Fintan’s belief in fairies: he is not only the stolid yang to Mickey’s frenetic yin. Fintan is a spiritual man, and in his modest way, a warrior against evil: he fights the want in Mickey that is the selfish, unmutual, disobliging want in us all. The thing that turns men into a mob.3

The last words they exchange come when Mickey has boarded Joe Locke’s boat, the Sea Spray, bound back to Liverpool to save his relationship and his club. He doesn’t hug Fintan or shake his hand goodbye, so eager is he to be on his way. But looking back, as the boat heads out into the harbor, a thought occurs to him. He calls back to shore:

MICKEY: What have I ever done for you?

FINTAN: Nothing. But it doesn’t matter.

They conclude with the farewell they must have learned as schoolboys together:

MICKEY: See you later, alligator!

FINTAN: In a while, crocodile!

There’s more to the movie: Mickey must reconcile with Nancy (who in a brilliant reversal, uses Mickey’s “I was born in peacetime” line to con a recalcitrant librarian—the only time in the film the line works), and stage a last concert in the half-demolished Hartley’s, while making sure that Joe (who in a lovely, almost Shakespearean parallel has reconnected with Nancy’s mother) doesn’t end up going to jail for the little matter of tax evasion. But what the movie has to say about music (there’s quite a lot of it; it’s practically a musical4) and romantic love pales, to my mind, with what it has to say about the friendship between men, and how they rescue each other—not through grand gestures or sacrifices, but by simply being present to one other in all their tender absurdity.

I have not yet seen Friendship (2025), the new movie starring Tim Robinson and Paul Rudd as two men who try to start a midlife friendship and fail abysmally. But I know Robinson’s persona from the hysterical series I Think You Should Leave and it represents perfectly the spirit of the mob in one buffooonish, rage-filled man compelled to double down on his awkwardness until catastrophe strikes. The mini-mob, if you will.

I first saw this movie in college with my friend Eric, the first straight guy I ever met who openly cultivated his softer side; both of us were confused about our masculinity and for a while we took shelter in each other’s confusion, going for long drives to nowhere in the middle of the night that involved too many cigarettes and way too many Chicken McNuggets. We were even involved with the same woman for a while—ai yi yi. After we saw the movie, “I hate things like this” became a kind of catchphrase between us. He went on to become an accomplished professional singer. Here’s to you, Eric—hope you’re doing well.

There is another fundamental difference between them, as Irishmen: Mickey emigrated to the U.K. in search of opportunity, while Fintan stayed put and started a family. Fintan, implicitly, has maintained a mystical connection to the land that Mickey rediscovers through his quest. Bringing the Irish tenor Joe Locke to sing—for free this time—to Liverpool’s emigre Irish community heals, at least for the moment, the lack in an immigrant’s soul.

The soundtrack is wonderful: